Kiwi Comedy On TV

Kiwi Comedy On TV

This collection has two backgrounds:

The Idiot Box — A Survey of NZ Comedy on TV

Making Homegrown Humour on Telly — The Trick of Cracking Up Right Here

The Idiot Box — A Survey of NZ Comedy on TV

By Diana Wichtel 01 Apr 2010

Two thousand and nine already. How did that happen? And this magazine [The Listener] celebrates its 70th birthday. It may be called The Listener but for nearly 50 of those years, it has also been busy watching television. So it’s a fitting time to look back at the sometimes oxymoronic (mostly just moronic) phenomenon that is television comedy in New Zealand.

"Viewer discretion is useless." — Back of the Y.

Misty water-coloured memories…most of my early ones are in black and white, and North American. In Canada, we couldn’t quite see Russia from our house, but we could see seven channels, many of them from across the border. I grew up spending far too much time avoiding school in a darkened basement watching I Love Lucy, Days of Our Lives, dodgy game shows like Queen for a Day (whining wins whiteware!) and other trash.

None of this prepared me for New Zealand television. When it became clear that my mother was transporting us, like a pack of small convicts, back to her homeland in the Antipodes, her family sent us copies of the Herald and, possibly, The Listener. I turned to the television pages and flatly refused to go.

By the time we arrived, television was four years old. It had been a long time coming, nervously held at bay as our leaders watched the rest of the civilised world for signs of the sky falling in. There were private experimental broadcasts from 1951, but, significantly for our comedy future, they were forbidden from broadcasting anything that might be considered 'entertainment'. Britain and the US had long since embraced this dangerous, anarchic, seductive new medium. New Zealand was petrified.

Nineteen sixty-four. AKTV-2 started at 5pm with Diver Dan or Clutch Cargo, and it was time for bed at 11pm. Weekend television started at 2pm but, certainly under my grandmother’s iron rule, it would have taken a brave soul to turn it on in daylight hours. Most of the programming was from overseas — Bonanza, Dr Kildare, Dr Finlay’s Casebook and some strange soap beamed in from another planet called Coronation Street.

In those days fathers knew best and women were vaguely dangerous. "Dr Kildare tries to protect an investment tycoon from a pretty nurse." There was — oh dear — The Black and White Minstrel Show. As always, there was television expressing anxiety about television. Huckleberry Hound: "Jinx thinks Pixie and Dixie’s favourite television show is nonsense."

On the dismal local front, there was Music Hall, with “the choicest songs of the season” from the likes of Miss Bertha Rawlinson, Mr Waric Slyfield and the Great Dedi. Who?

There was the violently boring Youth Wants to Know, a series in which "youth questions persons of maturity and standing in the community". On Sundays they signed off with a sermon — 'Rev JA Penman (live)'. I soon evolved a philosophy that has stood me in good stead over 25 years of writing about television for the Listener: you’d better laugh or you’d cry.

In the early 60s indigenous television comedy hadn’t been invented. Greer Twiss’ Puppet Playhouse was as good as it got unless you count pioneering gardening show host Reg Chibnall, who would eyeball the camera and demand, "Have you got crinkled weenies?"

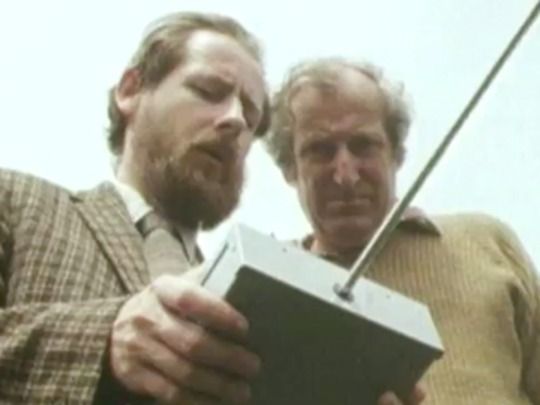

Humour began to sneak in thanks to Graham Kerr (Entertaining with Kerr) and his artery-clogging propensity for clarified butter. Auckland’s new regional show, Town and Around, or sometimes Country Calendar made kamikaze attempts to develop some indigenous comedy, attracting by default such talent as John Clarke and Barry Crump. The hosts became masters of the subversive gag. Town and Around’s Rhys Jones found a large vegetable on his workspace on some Welsh national day because, his co-host informed us, "he likes to have a leek on his desk". Well, I thought it was funny.

"We don’t know how propitious are the circumstances, Frederick." — Fred Dagg.

Never mind. We were lucky in one way. An advantage to our limited television landscape was that pretty much everyone in the country watched the same thing at the same time. It felt … cosy. I think that’s what we’re remembering when we recall some past Golden Age.

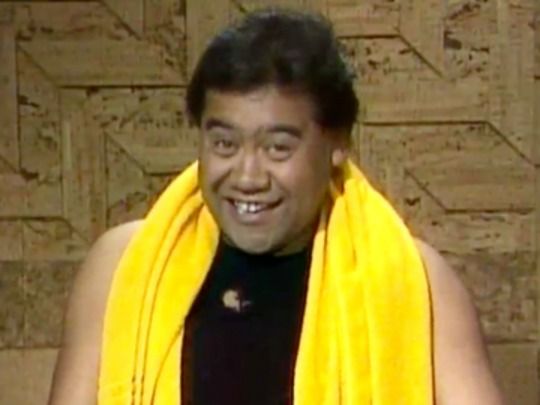

And it was handy for manufacturing cultural icons. Characters such as gumbooted provocateur Fred Dagg, jammed-on-transmit broadcaster Peter Sinclair, Lynn of Tawa, Billy T … A 70s survey revealed that 99 percent of New Zealanders recognised Fred Dagg. No one much remembers Neville Purvis (The Neville Purvis Family Show), but his creator, Arthur Baysting, advanced local television culture by being the first to say the 'f' word on air.

We were not so fortunate in other areas of comedy. The curse of the sitcom came upon us pretty much as soon we tried to make one. The first real example was Buck House in 1974, starring John Clarke and, of all people, Paul Holmes. Clarke has spoken about the sort of battles between television executives and creatives that dogged those early efforts, and many later ones. There was Joe and Koro, though for a bickering 70s odd couple, Hudson and Halls were a better bet. Then the dismal parade: For the Love of Mike, Porters … Even Billy T couldn’t save TV3’s The Billy T James Show, an attempt to find one of our few comic geniuses a sitcom vehicle. Melody Rules proved that imported sitcom experts were of little use unless you wanted to produce a shorthand signifier for epic awfulness.

There were honourable sitcom exceptions, two of them from the stage. Roger Hall’s Gliding On was like Waiting for Godot as played by the clerical workers’ union, a vibe taken to high art years later by Ricky Gervais.

James Griffin’s Serial Killers thrived on the postmodern notion of casting ex-Shortland Street stars, including Robyn Malcolm, just hitting her straps, in a series about writers working on a series very like Shortland Street. It was original and funny and so, of course, they gave it a bad time-slot and then canned it. But it suggested correctly that television about television is often the best television. Jaquie Brown was to confirm it a few years later with The Jaquie Brown Diaries.

But mostly we sucked. Satire was a safer bet. A Week of It made "Jeez, Wayne!" a national catch-cry. There followed some excellent impersonations of Rob Muldoon, Judy Bailey, Helen Clark, David Lange, Holmes, etc, leading to the general McPhail and Gadsby-isation of TV humour. Issues, More Issues… eventually we had issues with all those Issues, particularly since other excellent outfits, like Funny Business (Dean Butler, Willy de Wit, Ian Harcourt, etc), got short shrift. Despite such delights as their excellent alternative national anthem. Altogether now: "New Zealand is nice, New Zealand is good; New Zealand has sheep; New Zealand has wood…"

Meanwhile, Australians were showing how it was done, on big screen and small, often aided by New Zealanders. From Crocodile Dundee and Steve Irwin to Neighbours, Frontline, The Games and Summer Heights High, they were expert at mining their own dagginess and fearlessly caricaturing themselves.

Here, we had to wait for a generation who had grown up with television, were relaxed with its ways and its power and were prepared to make complete dicks of themselves. With shows like Luke and Robbo’s Chat Bungalow and MTV’s Havoc, things loosened up. If we are a nation of blokey boofheads, so be it. Cue Sportcafe, Back of the Y, Game of Two Halves and anything starring Marc Ellis and Matthew Ridge. You have to walk before you run. Or, in some cases, crawl.

Brian Edwards: "John Banks is horrific. He’s an idiot. He’s a dangerous idiot."

Bill Ralston: "Yes, but what’s wrong with him?"

As The Ralston Group demonstrated, news and current affairs could be comic. I recall one 70s Black Monday when every thing went wrong during the evening news. To footage of long-haired students sitting around a university quad came the doleful voice-over: "Tomorrow many of these dogs will be destroyed."

These days, news and current affairs is more or less indistinguishable from comedy. If only we’d had sitcoms as funny as the shenanigans at TVNZ, as Judy Bailey was all but forced to say, "And after the break, I’m sacked". They sold her clothes. There was Susan Wood’s wages debacle, Holmes’ "cheeky darkie" disaster, Mike Hosking’s midlife makeover …

Eventually, art, or a reality-inflected version, fought back and we got some world-class comedy: Wayne Anderson: Singer of Songs, Flight of the Conchords and The Jaquie Brown Diaries. For every delight there’s still a fright — Welcome to Paradise, Diplomatic Immunity — but even they earn the essential "not as bad as Melody Rules" accolade. Outrageous Fortune counts as drama, but it’s one of the funniest things ever made here. Defy the ghost of Melody, I say, and give Van and Munter their own sitcom.

What’s great television comedy? As the accompanying lists reveal, it’s very subjective. If television was only funny intentionally, God wouldn’t have given us C’mon, anything called Good Morning, Jude Dobson, Murray Mexted, Pete Montgomery, Michael Hill jeweller, John Campbell …

Television is off its head, out of its mind, erratic and ego-driven, just like the rest of us. Watching television comedy grow from anxious birth to spotty adolescence and beyond has been a rich and ridiculous, if often painful, pleasure. One thing I’m sure of: the best is still to come.

Reproduced with permission from The Listener, 1 August 2009 (Volume 219, number 3612)

-Diana Wichtel is an award-winning writer and TV critic. She has written for The Listener and The NZ Herald's weekly magazine Canvas. She investigated her family history in award-winning 2017 book Driving to Treblinka.

Making Homegrown Humour on Telly — The Trick of Cracking Up Right Here

By Roger Hall 01 Apr 2010

Once upon a time in a land long gone, we had only one channel. And a blissful time it was. Because last night’s TV was the conversational currency we all shared. We ALL watched The Forsyte Saga, The Power Game and Civilisation. When The Avengers was on, meetings had to be re-scheduled and you couldn’t get a taxi.

In those days a TV show was screened in Auckland. The next week it was shown in Wellington. A week later in Christchurch. Finally, Dunedin.

When In View Of the Circumstance (my first foray into writing for TV) was screened - rashly labelled ‘satire’ by some promotional person, which was the equivalent of giving it a Government Health warning - the ratings followed the same pattern. First in Auckland, second in Wellington, third in Christchurch, and last in Dunedin. We might just as well have called it No Laughing Matter.

But for the writer, especially that of comedy, it meant that the whole nation was sitting there waiting to laugh. Now we all know that if you go to a show that is labelled 'comedy' and it doesn’t make you laugh, you are annoyed; irritated; belligerent. A viewer in those days, following their pre-dinner sherry, the roast and three veg, and slippers up on the pouf, would sit through any form of drama because there is a story and you want to know what happens next.

Remember this was an age (I know most of you will find this hard to believe) when there was no such thing as a remote control. So it was easier to sit out a drama than roll off the couch and lumber over to switch off the Bell TV or the Philips K9.

But if youse was sitting there not laughing, well, crikey dick, this wasn’t funny. In fact, it was bloody annoying. And you said so! What was the Gummint doing spending money on so-called funny programmes? Everyone knows we can’t do it! Waste of taxpayers’ money etc. Dramatists got the same treatment if plays didn’t show New Zealand in a good light. Plays were supposed to show off our lovely lovely scenery.

New Zealand TV did import comedies, but only the best from (mostly) the UK and (close second) USA. So we chose only the best from a very large choice (I’m not quite sure how Gilligan’s Island got through, but there you are). We never saw the dozens of comedies that failed to make the cut in their own countries.

So we Kiwi humour writers were up against it. And, as I have often pointed out before, comedy takes getting used to. Monty Python succeeded only when the first series was screened again. One critic who had found it totally unfunny the first time around, on the second screening declared the very same programmes were works of genius.

But as a viewer, for sitcom to work, you’ve got to get to know those characters. Fred Dagg was drip-fed to audiences through appearances on current affairs shows and Country Calendar. Billy T was first introduced to viewers as Dexter Fitzgibbon on Radio Times, and McPhail and Gadsby were part of A Week of It. And luckily for me, everyone knew the characters in Gliding On from the first episode. They worked with them.

You still hear people say we can’t do comedy: we can we can we can! It’s just that our failures are more public than others. I suspect, given our population, limited resources, and Dunedin, we haven’t produced a bigger percentage of comedic turkeys than any other country. And what’s more New Zealand, and only New Zealand, had turkeys in gumboots.

- Roger Hall is New Zealand's most successful playwright. His play Glide Time was adapted into hit 1980s sitcom Gliding On. In 1993 he adapted his play Conjugal Rites into a sitcom for British television.