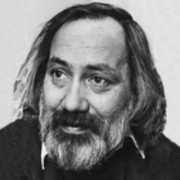

Barry Barclay

When Barry Barclay died in February 2008, MP Pita Sharples wrote that the director's work had given "voice to the voiceless, and helped people tell their own stories". NZ Herald writer Peter Calder called him "indisputably our greatest documentarian". Barclay's eloquence went beyond the screen: his 2005 book Mana Tuturu won praise for its exploration of indigenous rights.

Barclay grew up in the Wairarapa. His Pākehā father managed sheep stations, and his mother was one of the only Māori faces he remembered seeing in his childhood. Barclay's upbringing gave him a "deep respect for rural people". Later he would make it a creative yardstick to imagine how his films might play, if he took them back to his hometown.

Aged 15, Barclay joined a "fairly enclosed" Australian Roman Catholic order. He stayed roughly six years, inspired by the group's dedication to the values of poverty and community, but wishing there were some women present. During this period Barclay began to write, act, and paint. "But for some crazy reason I could not put my finger on, all I wanted to do was to make films."

Barclay was advised to get into television via radio. After time as a radio programmer in Masterton, he joined a local company making trade films. Over four years, Barclay became a skilled cameraman. "It was an invaluable experience. It taught me to look."

Around 1970 independent filmmaking outfit Pacific Films took Barclay on from the failing company, kickstarting a long collaboration with Pacific boss John O'Shea. Barclay found O'Shea uncharacteristically enthusiastic about putting matters Māori on film. Commercial work aside, one of Barclay's earliest Pacific films was half-hour TV short The Town that Lost a Miracle, an acclaimed and controversial remembrance of Opo the dolphin visiting Hokianga harbour.

But the first big milestone — for Barclay, and arguably for representations of Māori on screen — was the 1974 documentary series Tangata Whenua. As the show's originator Michael King later argued, Tangata Whenua broke the monocultural mode, giving Māori "an opportunity to speak for themselves about their lives".

Making the show taught Barclay much about Māori culture — and about how technology (for example long lenses, so subjects could be interviewed without having a camera right in their face) could be used to soften the impact of the camera´s gaze.

At the time Barclay kept quiet that he was a member of Māori activist group Nga Tamatoa, worried that 'breaking cover" might compromise the programme's funding. After Tangata Whenua's success, Barclay turned to Pākehā projects, wary of hogging Māori funding. Aside from a documentary on two master cloak-weavers (Aku Mahi Whatu), he directed Autumn Fires, Barclay's affectionate take on Pākehā culture, films on ex-soldier James Bertram (Hunting Horns) and Indira Gandhi (this made for an ultimately unrealised series) — and impressionistic short Ashes, whose mixture of fiction and fact included an early appearance by Sam Neill, as a conflicted priest.

Barclay returned home in the early 80s, after extended time overseas. Much of it had been spent working on the controversial and prescient documentary The Neglected Miracle, which examined ownership of plant genetics. Barclay decided to tell this story of crops and corporations trying to control them, by using the marae approach developed on Tangata Whenua: his hope was that everyone from third world farmers to scientists would get a chance to speak. Barclay argued in documentary The Camera on the Shore that big business "suppressed the film effectively". Within months of The Neglected Miracle's debut, he said, American network PBS completed a lookalike but far from soundalike film, with input from dozens of international companies.

MP Tariana Turia later argued that the film was influential in encouraging the Wai 262 Waitangi claim involving the protection of indigenous flora and fauna, and Māori traditional knowledge.

Barclay had hoped that Tangata Whenua would help open the door to more indigenous filmmaking. Returning to New Zealand, saddened by a lack of progress in this area, Barclay became a core member of Māori collective Te Manu Aute. Their constitution begins: "every culture has a right and a responsibility to present its own culture to its own people". In 1987 the organisation successfully pressured TVNZ to support landmark Māori anthology series E Tipu, E Rea.

The same year saw the release of landmark feature Ngati, set in a Māori-dominated coastal town in the 1940s. The film was written by Tama Poata, based partly on his own upbringing on the East Coast. Barclay described it in Scope magazine as "the first film made by an indigenous people, if you take indigenous to mean an indigenous minority living within a majority culture". Later he paraphrased academic Stuart Murray's argument that Ngati was a blueprint before its time of "another New Zealand in the making". Writer Cushla Parakowhai has argued that Ngati celebrates the values of community, "despite the persistent imperatives of technology and social change".

Barclay talked about how he hoped the film would give strength to Māori — young and old — in this Kaleidoscope piece. Wanting to show cultural sensitivity to the mainly Māori cast, he abandoned the tradition of using first assistant directors to keep the film on schedule; instead a team of inexperienced young Māori took on the job, and the film was shot in just five weeks. Some of them had just undergone training shortly before on Barclay's short film Ka Mate! Ka Mate! The director made similar training a condition for agreeing to direct Te Urewera, part of this series on New Zealand's national parks.

Barclay's second feature Te Rua (1991) told of efforts by Māori activists to take back indigenous carvings from a German museum. As documentary The Camera on the Shore makes clear, the project had a troubled run, partly because of the lightning rod topic, and the way fact and fiction were interwining. There was a last minute cancellation by a worried German museum where filming was set to take place, and later, major conflicts in the editing suite with producer John O'Shea. The film's premiere was a different matter. A Mohawk tribe in Canada spoke of how Te Rua had helped heal their spiritual wounds, when Te Rua had an emotional premiere there soon after the 1990 Oka Crisis in Quebec, which involved plans to build on a Mohawk burial ground.

In 2000, inspired partly by a Michael King book on the Moriori, Barclay made The Feathers of Peace. The film applied the groundbreaking fake-newsreel approach of 60s classic Culloden, to the fate of Chatham Islands Moriori. Critic Peter Calder found it "intelligent, dramatic, intensely absorbing".

In the 90s Barclay returned to the Hokianga. There he made his final film The Kaipara Affair, which examines a divided community uniting to halt the depletion of its fisheries (the film exists in both a 70 minute TV, and 133 minute film festival cut). Hokianga was also the place Barclay where finished writing his book Mana Tuturu: Maori Treasures and Intellectual Property Rights.

Peter Calder called Mana Tuturu the book that Barclay had been writing all his life, and it showed in "the meditative, almost tender, and conversational tone". Mana Tuturu expands on ideas advanced in earlier Barclay volume, Our Own Image. Barclay argues that indigenous perspectives and words should be incorporated into the legal documents that structure copyright, ownership, and accessibility — whether they involve land, nature, or the arts.

Barclay also played a hand in helping create film fund Te Paepae Ataata, a panel of Māori encouraging the development of Māori films.

Barry Barclay passed away on 19 February 2008, after a heart attack. He was 63. Graeme Tuckett's documentary Barry Barclay: The Camera on the Shore debuted as part of the International Film Festival the following year.

Barclay wrote in Mana Tuturu that having made films in both Māori and Pākehā worlds, he felt that with Pākeha film the main period of glory occurs when a film is initially released — but with Māori work, the film increases "in vigour and relevance" as the decades pass. It's a provocative statement, but perhaps a fitting end to Barry Barclay's rich career as an activist and filmmaker.

Moe mai e te rangatira, moe mai.

Sources include

Barry Barclay, Mana Tuturu: Maori Treasures and Intellectual Property Rights (Auckland University Press, 2005)

Barry Barclay: The Camera on the Shore (Documentary) Director Graeme Tuckett (Anne Keating Agency, 2009)

Barry Barclay, 'The Control of One's Image' - Illusions no 8, June 1988, page 8

Peter Calder, 'In memoriam: Barry Barclay: 1944 - 2008' - Onfilm, March 2008

Peter Calder, 'Barry Barclay: Mana Tuturu: Maori Treasures and Intellectual Property Rights' (Review) - NZ Herald, 23 March 2006

Stuart Murray, 'Images of Dignity - The Films of Barry Barclay' in New Zealand Filmmakers. Editors Ian Conrich and Stuart Murray (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007)

Cushla Parakowhai (Review of Ngati) - Art New Zealand no 45, 1987

Dr Pita Sharples and Hon Tariana Turia, 'Poroporoaki: Barry Barclay (Press Release) - 19 February 2008

Graeme Tuckett, 'A giant has fallen; remembering Barry Barclay' (Press Release) Loaded 22 February 2008. Accessed 28 February 2008

'Guards and resources' (Interview) - Scope, 2 April 1991, page 28