The Body Art Collection

The Body Art Collection

This collection has two backgrounds:

Tattooing and body art

Tattooing in the early 1980s

Tattooing and body art

By Sean Mallon 12 Apr 2022

"New Zealanders might be among the most tattooed people in the world" wrote Nicholas Thomas, a leading scholar of the history of tattooing in the Pacific. It was 1997, and he was referring to the visibility of tattooing on New Zealand’s streets and beaches, and in our general social and cultural life.

If we in Aotearoa New Zealand are indeed among the most tattooed people in the world, then NZ On Screen’s selection of television, film and video provides a valuable representation of the diversity of practices, meanings and affects that tattooing and body arts have had within our society.

At the time of writing, this selection focuses mainly on the practices of tattooing; but body art can also encompass skin piercing, body painting, branding, scarification and other kinds of self-adornment. We can include everyday activities such as trimming our hair, beard or eyebrows, our use of fake eyelashes and fingernails; even the painting of our skins with cosmetics, powders, lipsticks and perfumes.

This selection comprises a chronology of Aotearoa filmmakers’ engagements with body art, from the 1970s to the present day. The films offer insights into how the marking or decoration of our bodies speak to issues of history, culture and the challenges of modern life. They capture stories of creativity, politics, self-determination, cultural pride and identity.

A key example, Into Antiquity: A Memory of the Māori Moko (1972), introduces the last kuia (Māori women elders) who were the bearers of distinctive moko kauae (chin tattoos). However, from a practice that in 1972 appeared to be on the cusp of disappearing forever, Tā Moko (2007) documents how tattooing underwent a revival among Māori women and men, to become a powerful symbol of cultural persistence and identity.

Skin Pics (1980) and Signatures of the Soul (1984) were released as tattooing was becoming more visible in mainstream society and visual media. Director Geoff Steven pitched Signatures of the Soul to the state broadcaster as part of his interest in outsider type cultural stories. His documentaries were local and international in scope, and connected tattooing in Aotearoa to the countercultural renaissance, and tattooing practices in United States, Asia and the Pacific Islands.

One of the locales where Stevens filmed was Sāmoa, at a time when Sāmoan tattooing was starting to be practiced among a diaspora that had established communities in cities such as Auckland, Honolulu and Los Angeles. Tufuga ta tatau (tattooing experts) from Sāmoa worked in factories during the day, and tattooed at home in the evenings and on weekends. They undertook their work behind the closed doors of living rooms and garages, and only a few non-Sāmoans were involved. However, as seen in this profile of painter Tony Fomison (1981), a love of tattooing and art played a part in Fomison’s relationship with Sāmoans living in his Auckland neighbourhood.

Two decades later, Sāmoan tattooing was the subject of feature-length documentary Savage Symbols (2002). The audience for Makerita Urale's film included the children of Sāmoans that had immigrated in the 1960s and 70s, but also an international tattooing community that had become obsessed with indigenous tattooing.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the makers of Tattoo (2000) and Piercing – The Hole Story (2002) helped us appreciate how people create or find a sense of identity in the rituals, forms and processes of tattooing and other body arts. The personal testimonies in these documentaries reveal how body art has marked peoples suffering, but also marked their resistance and healing, their resilience and survival. Inside Tattooing (2012) offers a rare insight into the visual culture of Aotearoa’s criminal gangs and prisoners, which is often expressed through tattooing. It is at once a confronting set of images and interviews, but also a humanising account of painful pasts and hopeful futures.

In the last decade, for all New Zealanders — but particularly young Māori and Pacific peoples — film, television and the internet were key mediums for learning about tattooing and body art. Within the limitations of television formats and video sharing platforms such as YouTube, short form stories of tattooing and body art featured in magazine-type programmes, including episodes of Fresh and The Living Room (2002). Often they are short, punchy accounts of self-discovery and boundless creativity. Some of them are hilarious, others are moving. In contrast, other films are slower, intimate dramas, such as the short Tatau (2012) or supernatural movie The Tattooist (2007).

As more indigenous people get behind the camera and into the director’s chair, they continue to bring depth and nuance to the storytelling around tattooing and body art. Loading Docs 2016 - 'Aka'ōu: Tātatau in the Cook Islands highlights the work of a heavily-tattooed Englishman, Croc Coulter — an influential contributor to the revival of tātatau (tattoo) among Cook Islands people. Another highlight is Marks of Mana (2018), a landmark documentary by prolific director and producer Lisa Taouma. It features underrepresented stories of indigenous women and tattooing in the Pacific region. Leading practitioners and scholars offer indigenous perspectives on an art form that is going from strength to strength.

- Sean Mallon is the Senior Curator of Pacific Histories and Cultures at Te Papa. Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing, which he co-wrote with Sébastien Galliot, won the Ockham NZ Book Award for Best Illustrated Non-Fiction Book in 2019.

Tattooing in the early 1980s

By Geoff Steven 12 Apr 2022

Popular culture and outsiders...I've always been interested in what's bubbling away on the edges of our society, both politically and culturally. By 1980, I had already made some documentaries on supposedly edgy subjects. Te Matakite o Aotearoa - The Māori Land March and Gung Ho - Rewi Alley of China were well received, more political examples. Skin Deep was a feature about an outsider, a woman arriving in a small rural New Zealand town.

When the powers that be at the state broadcaster (then called the Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand) opened up a small window for us so-called 'independents' — a misnomer, since we were totally dependent on the two government-run TV channels to get in front of a wide audience — to direct some half-hour programmes, I readily took the plunge.

I had directed a couple of documentaries for the BCNZ, but this was different. This time we could use their crews and post-production facilities, and were freer in subject choice and style. I started with a half-hour film on graffiti called The Writing on the Wall (hosted by a mate, Tim Shadbolt!), and then looked around for another outsider type cultural story. Tattooing seemed like a good choice. It was visual, peopled by interesting characters, and at the time mainly hidden from the mainstream society.

Kiwi artist Paul Hartigan was making paintings of traditional tattoo flash (the off the shelf designs that adorn the walls of most parlours). At his exhibition opening I met some of those who were involved in Kiwi inking culture; and I used one of Paul's original artworks as the title graphic for Skin Pics.

A brave Māori man making his own facial moko was one of the one of the interesting and trendsetting people we discovered. Spelling mistakes, discreet bluebirds and anonymous artists were all part of the story.

After Skin Pics had screened, and been generally well liked by the audience, I started to research the role that the Pacific Basin had played in the evolving story of tattoo. I realised that as New Zealanders, we were in a unique position to tell a story that had strong links to our part of the world.

Signatures of the Soul became the vehicle to tell that story. We started off with Pacific Island traditional tattooing. The word 'tattoo' is supposedly the onomatopoeic version of the 'tap tap' sound that the early sailors heard when they watched the small hammer hit the sharpened shell blades — which the island nations artists use to make their patterns. We followed the maritime routes through to current sailors getting their marks of pride in the tattoo shops surrounding the US Navy fleet’s headquarters in San Diego.

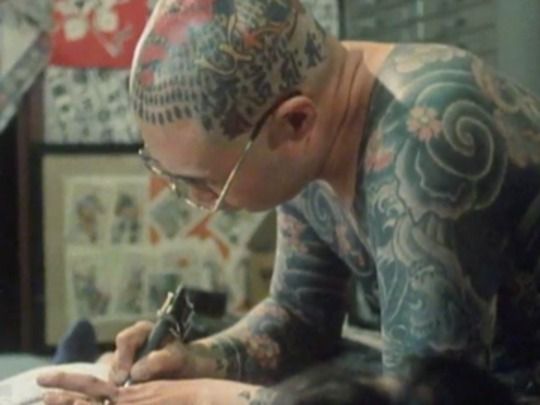

In East LA, we found Latino gangs and their black ink, prison-inspired photo realist portraits. In San Francisco we filmed with the famous Lyle Tuttle and his tattoo museum, and the contemporary artist Don Ed Hardy making large, full body works. Ed was following on from the Japanese illustrative work adopted by the mafia-like Yakuza gangs. It was an exciting and revealing shoot and we managed to get a privileged look into some closed worlds, particularly in Samoa, East LA, and with some actual Yakuza members in Yokoyama, Japan.

While we were editing the documentary I realised we had some pretty special material, and decided that we needed to give it an extra element to attract international sales. A high profile host would help with that; but we needed someone with an authentic connection to the counterculture and the "warm art" (tattooing was then becoming more accepted as an art; since skin is warm, tattooing was being called "the warm art"). In Los Angeles I’d heard that Peter Fonda of Easy Rider fame had tattoos. He definitely had the right cred, so I managed to track him down and we did a deal for him to host the show by shooting a series of links around LA that I could then drop into the edit.

"I’m a Fonda and I want to look good," was Peter’s main demand. Plus an envelope with an appropriate cash fee enclosed in it.

The first piece to camera was shot in a tattoo parlour down at Long Beach, and when word got out that we were shooting with Peter, the local chapter of the Hells Angels turned up to keep us company. It became an interesting four-day shoot, as we improvised to come up with links that could be integrated into the edited programme. We used a Japanese restaurant to do the Japan links, and tracked down the parlour where Peter had got his own small signatures of his soul.

The documentary's title comes from the opening link, where Peter talks about says tattooing being "the art form that shows the signature of the soul".

How relevant is that nowadays, when not having a tattoo seems more unique that actually having one? Only those who come out of a parlour proudly sporting their newly inked work can really answer that question.

- Geoff Steven founded filmmaking co-operative Alternative Cinema in 1972. He went on to direct documentaries and features (Skin Deep and Strata). After time as a programme commissioner at TV3 and TVNZ, he now leads Our Place - World Heritage, a photographic databank of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.