The Give It A Whirl Collection

The Give It A Whirl Collection

This collection has three backgrounds:

Giving It a Whirl

Winklepickers, a Lurex Tie and a Mohair Sweater

Women Musicians, and Making Music in the 1980s

Giving It a Whirl

By Michael Higgins 27 Apr 2022

Give It A Whirl was the first major documentary series to focus on New Zealand music. Over six episodes in 2003, it moved from the mid-50s and the thrill of discovery as the nascent art form trickled in from overseas, to the early 2000s when artists like Crowded House and OMC had gone out into the world and made an impact. Lorde was still at primary school.

The series was produced by Visionary Film & TV. We had a highly experienced production team, but we were also music fans who had spent time around the industry. My role was co-writer, researcher and associate producer; I had a background in radio and TV, and had written for Rip It Up. Producer and Visionary owner Richard Driver had fronted Christchurch punks The Doomed, followed by Hip Singles and Pop Mechanix. He'd also succeeded Karyn Hay as host of Radio with Pictures.

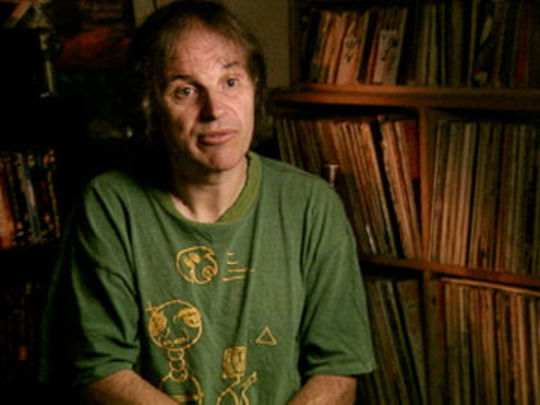

Director Mark Everton had been an announcer at Radio Hauraki and Bfm, and a fill-in for Barry Jenkin. Veteran music journalist Colin Hogg acted as script consultant, while field sound recordist Ant Nevison had been a Headless Chicken. Commissioning editor Irene Gardiner had worked in TVNZ’s rock unit and had looked forward to such a series ever since the publication of John Dix’s ground-breaking 1988 book Stranded in Paradise. Everton came to the show fresh from retracing Cook’s voyages on Captain’s Log. He brought with him cinematographer Steven Orsbourn, editor John Fraser and narrator Peter Elliott.

By the early 2000s, there was comparatively little music on our main television channels. With a few minor exceptions, music video shows like Radio with Pictures and Ready to Roll were long gone, and there was only the occasional documentary or special. The BBC had made major documentary series Dancing in the Street and Walk On By, while Long Way to the Top had told the Australian story.

A New Zealand series had been a long sought-after project. It was a glorious opportunity, but there was pressure. As Mark Everton told Greg Dixon in The NZ Herald, "we realised there was only one chance at this. The money was only going to be there once and if we [expletive] it up, then we might as well leave the country".

Split Enz, circa late 1970s. The band's costume mastermind Noel Crombie is on the left; next to him is Tim Finn, Eddie Rayner, Neil Finn, Malcolm Green and Nigel Griggs.

Give It A Whirl took its title from a 1979 Split Enz single. It was chosen to reflect a Kiwi spirit in an industry where there was often little to lose. At the heart of the Enz song was "a thrill you’ll never know if you never try" (although one or two interviewees took exception, claiming the title failed to recognise their professionalism).

The series could never be an all-embracing history. Lessons were learnt from Long Way to the Top. Its producers had shot career-spanning interviews with a wide range of artists and then attempted to structure storylines. Swamped with material, they described the experience as like trying to "stuff a doona (or duvet) into a beer bottle".

Whirl took a more targeted approach, adopting the tag line New Zealand Rock & Roll Stories. To paraphrase another Australian — songwriter Paul Kelly — the part would need to tell the whole. Significant stories and artists would be left out, but covering five decades in six hours was never going to allow time for everyone.

The reference to "rock & roll" was also telling. We saw it not as a genre but as an attitude, which could equally embrace reggae and hip hop. For Johnny Fraser, rock & roll was "music from the wrong side of the tracks…it was always the alternative". This focus did mean that there would be little room for the light entertainment which had played a prominent part on our screens in the 60s and 70s.

Any historical documentary needs strong archive, and holdings from the 50s, 60s and into the 70s were patchy at best. Early footage had existed largely on film, and its cultural significance would not be recognised for many years. With little storage space available, there had been a grim civil service efficiency to the way reels of film had literally been axed and sent to landfill. This was by no means an exclusively local phenomenon. The BBC similarly trashed a vast swath of 60s footage, including Top of the Pops episodes featuring The Beatles, Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan.

As film gave way to videotape, a new threat presented itself. In the pre-digital era, tape was far too expensive to use once, then archive; deletion lists made their way around TVNZ offices well into the 80s.

As a result, only two representative episodes from three years of C’mon had been kept (and nothing from its predecessor Let’s Go or more middle of the road successor Happen Inn). Where footage survived, it often reflected that light entertainment bias. This became an obstacle to any meaningful coverage of the progressive rock scene in the late 60s and early 70s.

A performance from popular and now largely destroyed 60s music show C'Mon.

The limited state of the archive led one former producer to strongly urge that the first episode should encompass the 50s and the 60s. The advice was noted but not followed.

A footage search launched to locate film and video held in private hands paid off almost immediately: it yielded priceless footage shot by Ron Crabtree in 1956 when he aspired to make a rock’n’roll film. It was enough to make the campaign worthwhile (and needed to, because very little else surfaced). Crabtree’s images played an important role in the first episode. But Mark Everton also saw the footage as emblematic of a feel he was looking for, and based the show’s title sequence around it. The theme music was composed by Dudes/DD Smash guitarist Ian Morris.

Extensive use of still photos helped to fill the void. From Wellington, Larry Jordan provided a number of previously unseen shots from the early 70s with subjects including Dragon (before they decamped to Australia) and the original line-up of Split Ends (possibly the earliest live shot of them, at Ngāruawāhia in 1973).

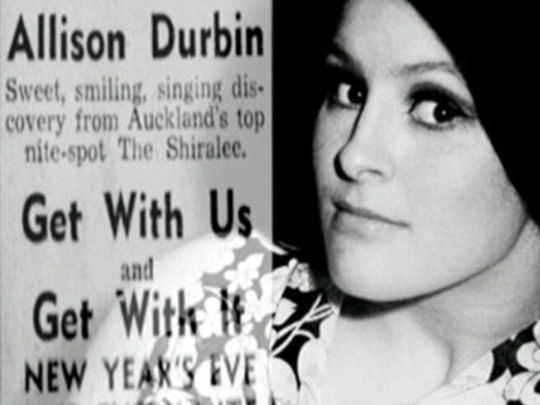

The backbone of the series came from more than 70 interviews shot throughout New Zealand, as well as in London, Melbourne and Sydney. Big names were accounted for in Johnny Devlin, Max Merritt, Dinah Lee, Ray Columbus, Allison Durbin, Tim and Neil Finn, Dave Dobbyn, Don McGlashan, Graham Brazier and Dave McArtney, Martin Phillipps, Mike Chunn, Chris Knox, Jon Toogood and Shayne Carter.

Equally important were the stories of those outside the limelight or behind the scenes. Record company executive Dave van Weede saw the potential in rock’n’roll and pressured country singer Johnny Cooper to cut a version of 'Rock Around the Clock'. Peter Dawkins produced some of our most enduring hits (including 'Saint Paul', 'Nature' and 'April Sun in Cuba’). Mike Rudd, from mid-60s Christchurch cult legends Chants R&B, later wrote one of the great 70s Australian anthems, 'I’ll Be Gone', with his band Spectrum (a song still little known in his native land).

Johnny Cooper, who sang on New Zealand's first rock'n'roll recording in 1955, with his band: from left, Will Jones, Jim Gatfield, Cooper, Ron James and Don Aldridge.

A number of interviewees are no longer with us. Jane Walker, Max Merritt, Bones Hillman, Peter Dawkins, Johnny Cooper, Dalvanius Prime, Ray Columbus, Rick Bryant, Graham Brazier, Dave McArtney and Ian Morris are all very much missed, but the series captured them and acknowledged their contributions.

The show was given the coveted 8.30pm slot on TV One on Monday nights, and began screening on 26 May 2003. There was a launch function at Galatos. The extensive publicity campaign ran to billboards and double page ads in The Listener. Giant banners festooned the TVNZ atrium for weeks.

Hello Sailor members (from left) Dave McArtney, Harry Lyon and Graham Brazier, during their Give It A Whirl interview.

There were inevitable questions over the omission of particular artists. Debbie Harwood, who had topped the charts with When the Cat’s Away, felt the contribution of women was under-represented, and responded with her radio series Give It a Girl.

The critics were largely kind. Omissions were also on Graham Reid’s mind, in an otherwise favourable NZ Herald review of what he called "an intelligent and remarkable series". Diana Wichtel concluded in her Listener review that "this sort of cultural history is what television can do like no other medium and, so far, Give It A Whirl is doing it well". Jane Clifton was of similar mind in The Dominion Post, noting that the series "shows New Zealand TV is growing up — telling us about ourselves, often in an unsentimental way".

It wasn’t all plain sailing. A netball test and a live special testing the nation’s IQ saw Whirl preempted from its prime timeslot on several occasions, and a key sequence from the first episode had to be cut at the last minute when rights to use 'Till We Kissed' couldn’t be secured. A CD soundtrack on Simon Grigg’s Propeller Records was banned from sale by The Warehouse because of a four-letter word writ large in a Shayne Carter quote on the back page of the booklet. C’mon producer Kevan Moore’s complaint about a Larry Morris quote was upheld by the Broadcasting Standards Authority.

In those pre-streaming days, the only on-going presence was a DVD release for schools, which had to be edited to be suitable for 10-year-olds (the lower age limit for pupils at rural area schools). Rights issues meant a commercial DVD version was untenable, and the show faded from view after its two replays had been exhausted. A second series filled in gaps with a more thematic approach in 2006.

Director Mark Everton regards Give It A Whirl fondly. He was "thrilled that it was so well realised, beautifully edited and wonderfully presented". It deserves to be seen again, and should be essential viewing for anyone wanting to understand the first five decades of New Zealand popular music, and the role it has played in the sounds this country makes today.

- Music fan Michael Higgins managed Canterbury University's Radio U before two extended stints at TVNZ, as a writer, researcher and later producer. He went on to spend three years as programme director at Kiwi FM.

Sources include

Jane Clifton, 'Teleview' (Review) – The Dominion Post, 28 May 2003

Greg Dixon, 'How the Shaky Isles got rockin' (Interview) - Weekend Herald, 24 May 2003

Graham Reid, 'Give It a Whirl, the final' (Review) - The NZ Herald, 13 July 2003

Diana Wichtel, 'The Beat Goes On' (Review) - The Listener, 14 June 2003

'Give It a Whirl: How The Shaky Isles Got Rocking' (interview) Take 33 (Screen Directors Guild of New Zealand Magazine), October 2003

Winklepickers, a Lurex Tie and a Mohair Sweater

By Harry Lyon 27 Apr 2022

It was the summer of 1958/59. I was eight and it was the first time I went on holiday without my parents. My little mate was the youngest in his family by some years and they called him Bubs. I was Bubs’ mate and I called his mum Auntie Merle, even though she wasn’t actually my aunt. They had a bach in Cornwallis on the Manukau Harbour, so it was a classic Kiwi summer with swimming, sailing, fishing and just running around exploring.

At some point there was a teenage party at a place along the beach. Auntie Merle said us boys could go for a while, with one of Bubs’ older brothers to keep an eye on things and bring us home. I was introduced to four new things at that party; Fanta, potato crisps, bodgies and Elvis Presley. It was the last two that had a life-changing effect on me. The kid hosting the party was fully kitted out in a drape coat with leopard skin lapels, stove pipes, brothel creeper shoes and a quiff. When 'One Night With You' hit the turntable, a very impressionable Harry thought "“I wanna look like that, and sound like that". Within the year I had saved my one shilling a week pocket money, and dragged my mother off to Beggs-Wisemans in Takapuna to buy a Suzuki No. 6, nylon string acoustic guitar.

Fast forward a few years and I had arrived back in New Zealand after two years living in England, where my father had been sent for work. By then I had a Watkins Rapier electric guitar, an amplifier, several pairs of winklepickers, lurex tie, mohair sweater, long trousers (!) and way too much attitude. Still they proved to be a fatal attraction to a young David McArtney, who had moved into the neighbourhood in my absence. Within weeks Dave had a drum kit, and joined another kid in the class, Craig, a really capable rhythm guitar player, and me. We couldn't find anyone to play bass so we were a trio,and played mostly Shadows covers. We were popular at our classmates' thirteenth birthday parties and entertaining visiting relatives at our various homes. We did play at a neighbouring school dance, and for the kids at the local IHC school.

The McArtneys moved to Wellington in 1964 when Dave’s father was transferred. We kept in touch and I went down to stay with them in May 1965. Dave came away to the Bay of Islands with my family the following summer. We used to write letters to one another filled with dreams of having a band, with drawings of a stage set-up as a projection of our futures.

All this coincided with the 1960s Britpop phenomenon — The Beatles, Stones, Kinks, Who and others, who all toured New Zealand. My aunt worked at George Courts that had the booking office for these shows, so I saw most of them, in many cases from the front row. That was the case when The Rolling Stones came for the first time in 1965. A friend and I were rabid Stones fans, and had seats front row in the middle of the Auckland Town Hall for their show. Ray Columbus and the Invaders opened, and I was knocked out at how good they were.

Hello Sailor in 1985. From left to right, Dave McArtney, Ricky Ball, Harry Lyon and Graham Brazier.

I’d been playing for six years and could really see what was going on from that close to the stage. I loved the Stones set, but thought as a band Ray and Invaders were their equals. That made me start to think that Kiwi bands could be as good as anything international. I’d already been a fan of Johnny Devlin, Johnny Cooper and Red Hewitt, but was too young to see them live. By 1966 and my fifth form year I was in my first semi-pro band, The Legends. We often played alongside other bands so I was exposed to a lot of local live music, as well as going to see the (mostly) British acts that toured. I joined The Crying Shame in 1967, my sixth form year. They played more regularly, often at inner city clubs like The Bo Peep, The Monaco, The Galaxie, and in 1968 a residency at The Bowl Ballroom, a dive at the bottom of town.

There were some 35 live music venues in the Auckland CBD in the mid to late 1960s, with bands like The La De Da's, Larry’s Rebels, The Action, Underdogs, Dallas Four and The Troubled Mind holding down the residencies at the main clubs. Along with acts like The Chicks, Sandy Edmonds, Mr Lee Grant, they were all recording and releasing material, touring and making regular TV appearances on C'mon, which screened in prime time on Saturday nights. They were stars and household names. I got to see them up close a lot and soaked it all up...the look, the moves, the models of guitars and amplifiers they used, the type of material they played.

In the 1980s Larry Morris and I were boundary fielders at a musicians’ social (beers at your feet for between overs) cricket game. I told him I met my wife at a Larry’s Rebels dance at the Takapuna RSA Hall on 17 June 1967. He loves that story to this day, especially because Maggy and I are still together after some 50 years. When I see him he always asks "How’s that beautiful wife of yours?".

By the time the 1970s came around Dave and I were both at Auckland Uni, and were flatmates in a Parnell house. We lived a pretty bohemian lifestyle, played our guitars constantly and in 1972 dropped out and vowed to start a rock’n’roll band.

We were big on singer-songwriters; Bob Dylan, Crosby, Stills, Nash and (especially) Young, Joni Mitchell, Carole King. Rock’n’roll was still fueled by the Stones’ Exile on Main St. and Sticky Fingers, Bowie and the Velvet Underground, plus the influence of our love of Tamla Motown and Atlantic soul music. Local bands like Highway, The Fourmyula, Space Waltz, and Split Enz played original material and showed us there was a growing acceptance of music that had Kiwi imagery. Dave and Graham were living in the infamous Mandrax Mansion in St Mary’s Bay, and Hello Sailor was rehearsing and looking for work by early 1975.

There had been some great original local songs since Ruru Karaitiana’s 'Blue Smoke' and Johnny Cooper’s 'Look What You’ve Done (Lonely Blues)'...'Hush Not a Word to Mary' and 'Cheryl Moana Marie' from John Rowles, and Kiwiana hits like 'Opo the Crazy Dolphin', 'Down the Hall on Saturday Night' and 'Taumaranui on the Main Trunk Line'. But most local artists recorded and performed covers of songs sourced from overseas. In the 1970s there was a shift, with acts like Dragon, Waves, Street Talk, Sharon O’Neill, Th’ Dudes, Citizen Band, Hello Sailor and others releasing their own material that started to give our young country its own songs to sing.

Those that followed have cemented a place for New Zealand music on the world stage. The 1980s gave us indelible hits from Neil Finn, Dave Dobbyn, Shona Laing, Jordan Luck, Chris Knox and Martin Phillips. The 1990s saw the emergence of Polyfonk with Ardijah, hip hop from Dawn Raid, a megahit in 'How Bizarre' from OMC, Kiwi reggae from Herbs and Tigilau and Ché Ness, and songs in te reo thanks to The Pātea Māori Club and Moana. Shona Laing and Sharon O’Neill lead a pantheon of great Kiwi women songwriters like Bic Runga, Jules and Linda Topp, Brooke Fraser, Julia Deans, Gin Wigmore, Kimbra, Hollie Fullbrook, Aldous Harding, Anika Moa, Mel Parsons, Ladi6, Pip Brown (Ladyhawke), Tami Neilson and Lorde.

A young Jordan Luck from The Dance Exponents.

In 1981 I was playing in The Legionnaires and we had a few nights booked at the Aranui Hotel in Christchurch. The Aranui's resident band opened for us. They were young and obviously popular with the locals — especially the singer, who had a great voice and charisma to burn. They also had a repertoire of disgracefully catchy original songs. They lived in the 'band house' just down the road, and invited us back for drinks after the gig. They were great company and there were plenty of laughs. Back in Auckland I ran into Mike Chunn, who was then representing Mushroom Records in New Zealand. When he asked what I’d been up to I told him about Christchurch. "See any good young bands?" he asked. I told him about the Aranui band: The Dance Exponents. I wasn't surprised when I found out he'd signed them.

In 2022 Kiwi music is diverse and has new stars: Six60, Marlon Williams, Tami Neilson, LAB, Stan Walker, Broods and Benee. From modest beginnings, the New Zealand music industry now sees local acts playing major venues here and internationally. If you’re considering a career in music, Don’t Dream it’s Over. Think of 'How Bizarre' and 'Royals': you’re one song away from being an international act — Give it a Whirl!

- - A founder member of Hello Sailor, Harry Lyon spent seven years as Dean of the Music and Audio Institute of New Zealand, before releasing his first solo album To the Sea in 2018.

Women Musicians, and Making Music in the 1980s

By Debbie Harwood 27 Apr 2022

This piece by Debbie Harwood was first published as the introduction to Ian Chapman's 2010 book Kiwi Rock Chicks, Pop Stars & Trailblazers

There is a social conditioning, etched into our DNA, that means when a question is asked such as "name New Zealand’s top songwriters", our minds automatically veer into XY territory — we think of the men first. I do it, I'm as guilty as the next man: it's an old primal response. We would all say Neil Finn, Dave Dobbyn, Jordan Luck, Graham Brazier, Dave McArtney, Don McGlashan, James Reid, etc, first up.

But the truth is that the women writers in this country — like Sharon O’Neill, Shona Laing, Margaret Urlich, Annie Crummer, Bic Runga, Brooke Fraser, Jenny Morris, et al — have matched these icons in sales and in chart placements. It's just that sometimes we forget. And when you pit song against song in deft writing, the beauty of melody-against-chord and eloquent lyrics, gender becomes terminally redundant.

I have inadvertently become a champion for women singer-songwriters, not to wave the female flag or rant on bitterly about women being under-appreciated, but merely to restore balance. I am fighting human DNA programming here. New Zealanders should experience the joy of listening to these women's voices and songs, and the women deserve to have the opportunity to perform their works to appreciative crowds.

Singer/songwriter Sharon O'Neill, in 1978.

With much love and respect to our peers — the great male writers in New Zealand — they regularly get their dues and are oft revered, so they are already taken care of. So, to me, Kiwi Rock Chicks, Pop Stars and Trailblazers, Ian Chapman's book on New Zealand women in rock is more about honouring the great songs these women have written than anything else — 'Glad I'm Not a Kennedy', 'Escaping', 'Room That Echoes', 'Asian Paradise', 'Maxine', 'Lydia', 'Language', 'Luck's On Your Table', 'See What Love Can Do'… These songs all stand side by side in their impact on the history of New Zealand music, and side by side in their success and popularity. It's a reminder that there have been more than a handful of prodigious writers' songs gracing our airwaves and charts.

When I was a young person, women were outnumbered in the business by perhaps 100 to 1. The music awards were awash with lyrical testosterone. I loved it, as I'd had a deep mistrust of women ingrained in me by my self-professed misogynistic mother, so touring New Zealand with a bevy of blokes was a comfortable state. I liked being "one of the boys", and it took me quite a bit of adjustment to get used to the close and constant company of the other four women in When The Cat's Away: Annie Crummer, Dianne Swann, Margaret Urlich, and Kim Willoughby.

And on the road there is no room for bullshit or ego; life is tough out there for a musician. You slog it out: it is a myth that you just "make it". It takes enormous bottle and humility and talent to be a touring musician in a tiny country like New Zealand. I learned to love these women and their magic — my misogynistic leanings were soon righted — and I saw that gender is not an issue in the making of music.

The cover of When the Cat's Away's self-funded number one single, released in 1988.

But the attitude to women artists in New Zealand was highlighted for me when the TV series Give It A Whirl was made. It was then that I realised that our women are not given the same reverence that the men are — and it is much the same with food and painting — the men are deemed to be more "valuable" than the women. I have a theory on this: 95 percent of all music critics are male. In most cases they are people who wanted to be musicians (but often weren't) and ended up in the critic's chair. You see, these men aspire to be like their musical heroes, who are men; they certainly don't aspire to be Annie Crummer or Bic Runga. So the focus and emphasis is from their personal perspective.

I had anticipated Give It A Whirl with the same enthusiasm I had for Radio With Pictures in the early 1980s, and it started off brilliantly. The 1960s and early 1970s were full of women in miniskirts singing great songs: C'mon and Happen Inn featuring Dinah Lee, The Chicks, and more. But by the time we reached the week that highlighted Dragon, I realised that New Zealand’s first rock chick and iconic singer-songwriter, Sharon O'Neill, had been overlooked ... and then Jenny Morris ... then Ardijah, featuring Betty-Anne Monga... then When The Cat’s Away — the list went on.

As subsequent programmes aired featuring male-dominated acts, I presumed that the producers must have been holding back the women for one celebratory episode — why else would they be missing? These women had produced multi-platinum albums, released numerous number one hit singles, had played to sell-out crowds, produced huge radio hits, and above all were loved by the New Zealand public. I was so intrigued that I rang the director and was stunned to hear that all of their stories had been dropped from the series. That is not a definitive history of NZ rock'n'roll! I believed that this needed to be remedied. So I set about making a radio series called Give It A Girl – The History of Women in New Zealand Music. Someone had to do it.

Margaret Urlich (in checkered outfit) in When the Cat's Away. From left, Dianne Swann, Debbie Harwood, Kim Willoughby, Urlich, Annie Crummer. Photo credit: Paul Ellis.

Margaret Urlich went three times platinum in Australia with her album Safety in Numbers, which featured her number one hit 'Escaping'. She has sold more than 400,000 albums in her career. I saw the charts in Australia at the time: Margaret rubbing shoulders with Midnight Oil and John Farnham. She had been big in New Zealand with Peking Man, and even bigger as a solo artist and with When The Cat's Away, then repeated her success on an even greater scale in Australia. Between them, Jenny Morris and Margaret Urlich have sold over 900,000 albums. It occurred to me that New Zealand women singers/musicians have enormous public appeal but little respect from the industry, which has been reflected in the books written and documentaries made. The public, however, love them!

The New Zealand rock'n'roll road has been an interesting one, and we only have a 50 year history. The singer-songwriter emerged strongly here in the 1970s, which saw a crossover between traditional radio and music recording, and a more anarchic approach. Radio New Zealand still had large recording studios in Wellington, where radio plays, orchestras, soundtracks and albums were recorded for broadcast. Music television was being produced with young singers and dancers being groomed and trained within the TVNZ structure. Programmes such as 12 Bar Rhythm 'n Shoes were being produced, and much of radio and television had a 'cabaret' approach. There were in-house producers in radio and record companies, and musical conservatism was rife — excepting a small vessel which, from 1966-1970, had dropped anchor out in the Hauraki Gulf and began broadcasting New Zealand rock! Once onshore and legit, Radio Hauraki continued to keep New Zealand music on life support while it battled to survive.

By the mid-1980s, radio stations had changed their formats, employing American consultants and following the charts and airplay of American magazine Billboard. FM radio and compact discs were introduced with much chest-pounding, and the advent of the big American over-produced songs began. New Zealand’s pop/rock songwriting sensibility, which was organic, melodic and lyrical (and played by actual musicians), now had no medium. For a while "the New Zealand sound" was silenced, and only bands that made the adjustment to programmed/sequenced recordings and overblown production survived — and even then, most New Zealand recordings were rejected by radio.

In the early 1980s, the pub-touring circuit that had been continuously circumnavigated by the great pop/rock bands of the late 1970s and early 1980s (Hello Sailor, Dragon, Blam Blam Blam, Hip Singles, The Mockers, Big Sideways, Citizen Band, etc) wound down as the DB and Lion hotels were sold off. Most of the bands were left in debt. As punters replicated stamps on their wrists outside the venues and climbed through toilet windows to avoid a door charge, it was clear that they didn't realise (or possibly care) that it was the bands who took the financial risk, paying for all touring and marketing expenses, their only revenue being the few dollars they gathered at the door.

Auckland, in the early to mid-80s, had The Gluepot, the Esplanade, The Windsor Castle, The Rumba Bar, The Reverb Room, the Mon Desir, the Downtown Convention Centre, Wildlife, the Windsor Park, and more, as prominent live venues. During the 80s, they began to be systematically turned into apartments or shut down, changing forever the six-day-a-week live-band culture that had been such a vibrant part of Auckland city. Most bands either bailed to Australia or broke up. To survive this time was a feat of endurance: New Zealand music was an endangered species.

There was no NZ On Air, and radio viewed New Zealand music with abject disdain. By the mid-1980s, television heads had decided that the great unwashed didn’t want to see music entertainment on TV, and ceased most New Zealand music television production.

All of the members of When The Cat's Away had toured for years in original New Zealand bands. As the touring circuit dissolved and radio shut its doors to New Zealand music, surviving as an original New Zealand band became almost impossible. Most musicians at this time found work washing dishes and working in restaurants to support their music. And because there was no funding, all videos had to be paid for by the artist; I waitressed for a year to save enough money to pay for a video ($3000) which was aired, at the most, three times on television.

At this time, as video became the new radio, New Zealand artists were competing with the huge video budgets of overseas bands. Our videos looked tragic in comparison, and it perpetuated the self-effacing New Zealand attitude that New Zealand music was crap. It was a tough time. The only way to get to the people at this time was to tour the length and breadth of New Zealand, relentlessly building up a live fan base.

The Cats toured for two and a half years before 'Melting Pot' was released. As the single shot to number one in 1988, the industry was incredulous. Considering the lack of support at the time, our success was like a flower cracking through concrete! The sharemarket crash had just happened, and the New Zealand public loved the band because we were optimistic and energetic. Sometimes I felt like Vera Lynn cheering up the troops. The preference would have been that our original bands had been supported by radio and the public, so we reluctantly accepted the huge success of the band, never fully standing in the glare of it. There was a little bit of bitterness at the necessity of forming such a band: a band that was born out of exhaustion from trying to get airplay and support for our original music, a band that was supposed to be merely a short break from the slog.

When our album and single reached gold status we were presented with 'gold' cassettes — an ordinary cassette mounted on red faux velvet. Only international bands were released on CD at the time: New Zealand music's status was at an all-time low.

In 1990, Mike Chunn, the original bass player with Split Enz and Citizen Band — New Zealand’s most dedicated Kiwi music exponent — began his reign at APRA (the Australasian Performing Right Association). Things started to change: New Zealand now had a New Zealand songwriters' sheriff. The APRA Silver Scroll Award, which celebrated the finest song of the year (regardless of commercial success), was attended in 1982 by around 100 people. In 2004, there were more than 3000 members, and tickets were in demand as the event was able to seat only 1000 [See this AudioCulture article].

As the 1990s began, NZ On Air was formed, with Brendan Smyth taking the helm as manager of its music initiatives. Radio initially resisted, ignoring, giving away or dumping the Kiwi Hit Discs from NZ On Air, which had a bunch of great New Zealand songs on them to make it easier for radio to listen to and programme the songs. Video funding was introduced, and so began the regular archiving of our musical voices and faces. Record companies committed to giving local releases the same priority and marketing push they were giving international releases. The public, for the first time, saw our artists and international artists side by side, without the poor-cousin impression that had been perpetuated by bad photos, videos and promotion. New Zealand music and bands had always been brilliant and prolific, but previously could not compete with the images created by the big budgets for international artists.

Singer Jenny Morris in 2008.

Over the next 10 years, radio gradually began to soften, and NZ On Air, APRA and the record companies kept chipping away methodically, tapping that wedge gently, without let-up. It wasn’t without its frustrations, but everyone endured by remaining positive and presenting radio and television with incredible songs, videos and recordings. The past few years have seen a massive shift — it was a critical mass situation: suddenly it was "cool" to love New Zealand music; it became the preference. New Zealand Music Month was launched, and is proudly celebrated every year. Airplay of New Zealand music has increased from just over 2 percent in the early 1980s to nearly 30 per cent on some stations today [2010]. Now, more than ever, there is a chance that a musician will "make it" in New Zealand.

Women musicians such as Sharon O'Neill, Shona Laing and Jenny Morris helped pave the way, by following their passions with or without support or return, and it is on the shoulders of these women of the vanguard that Bic Runga and Brooke Fraser now stand, as will many more in the future. Unlike sport, there is no "muscle" in creativity, no difference in potential or power between the sexes. The women have stacked up single after brilliant single, just like the men, driven around New Zealand in the same Bedford vans, performed on the same stages and to the same audiences. There is no difference between the men and the women in experience or output when it comes to music. And that is one of its blessings. Now when I go to RockQuest or to one of the pioneering Play It Strange concerts for high-school songwriters, I am stunned and delighted to see that the ratio of male to female is now more like 50 to 50.

We're all in this together, and it comes down to one thing: a great song is a great song.

- NZ Music Hall of Fame inductee Debbie Harwood has performed solo, in supergroup When the Cat's Away, and with her Band of Gold. In 2005 she created radio show Give it a Girl, after initial hopes for a TV series.

This piece was first published as the introduction to book Kiwi Rock Chicks: Pop Stars & Trailblazers, edited by Ian Chapman (HarperCollins, Auckland, 2010). Republished with permission.