The Sam Neill Collection

The Sam Neill Collection

This collection has two backgrounds:

Sam Neill: a private man in a public business

Sam, I have your iPod

Sam Neill: a private man in a public business

By Ian Mune 11 Sep 2017

Actor, winemaker, bon vivant, self-deprecating famous person: Sam turned 70 this year. (It’s no secret; his birth date is on IMDB.) That’s 50 years plus in the acting trade.

Sam’s a very private man who has found himself in a very public business. He doesn’t really enjoy all the interviews and promos, and indeed publicly disavows his fame even while he is being interviewed about his fame. It’s a kind of reductio ad absurdum. Sam’s view? He “scuttles round the edge” of fame.

This determined modesty is a very Kiwi trait, earning him the affection of Kiwis everywhere, even if it is spiced with a naughty wit.

But it’s this public/private element that interests me. Actors, like it or lump it, have to be prepared to expose something of themselves, indeed mine themselves for the material of their performance. You can spot the ones working on theory as against those bringing something of themselves to the performance. The theory ones work on skill and charm, the miners, while still having plenty of charm, and plenty of skill, work with something else, something deeply personal that they publicly share. And, interestingly, many of them are deeply private people — Brando, Montgomery Clift, Chaplin, Eastwood. And Sam.

So let’s have a look at a few of the performances. And God knows there’s plenty to choose from. I don’t know any other actor who has chalked up at least one movie, and often three or four, EVERY year since Sleeping Dogs in 1977. PLUS a similar amount of TV Series and TV Movies. AND nine directing, four writing, three editing and three producing credits. Not to mention Two Paddocks vineyard.

That’s a lot of lines to learn. Not all those shows will be on anyone’s top ten list, but there are some goodies in there. Some good for fame — Jurassic Park, Reilly: Ace of Spies — some distinctive, with work of distinction from Sam — Evil Angels, Death in Brunswick, The Piano, The Tudors, The Dish, Dean Spanley, I could go on. I haven’t seen all Sam’s work. If I tried that I’d never see anything else. But there is a consistency there, and a good quality to have — integrity.

Take a another look at his Michael Chamberlain in Evil Angels. This is a living person he’s playing, a man who has been through an appalling experience and was still going through it when the film was made. Sam studied him carefully, and his very fine performance treats the character with truthfulness and respect. It is a very contained performance, and one I rank right up there.

Sam doesn’t do flashy. On-screen or off. If he doesn’t believe in it, he doesn’t do it. I wrote a line for him as Smith in Sleeping Dogs. Seeing the island that is to be his home, Smith says “Yabba-dabba-doo!” and kicks the tyre of his car. Clearly, this is not Shakespeare, but it’s not total crap. Before shooting the scene, Sam asked me “Ahhm… Ian, how do you think I should do this Yabbadabbadoo bit?” “Don’t worry about it” says I, “it’s just a eureka thing.” “And I kick my car. Why would I kick my car?” In the end, Sam looks at the island, goes to his car, does a hesitant little shuffle and taps the bonnet. Well, good on him. As writ, it would have been flashy.

But look now. Cardinal Wolsey, one of the few characters with any historical integrity in the historically execrable Tudors. It's a big, colourful performance. Without being flashy. Dean Spanley. That’s out there. And, possibly my favourite, the driven, conflicted, corrupt cop, Chester Campbell, in Peaky Blinders. The self-loathing of the man is startling. I’m sure Sam doesn’t loathe himself, but we all have times we don’t exactly like ourselves. This is definitely one of those performances where the actor mines himself and shares it publicly. And for all its force, still not flashy.

It’s all about what’s held in reserve. Even with a portrayal as vivid as Chester Campbell, there’s always something more that’s held back, so we sense it rather than see it. And it’s the wonder of cinema that the camera reveals things that the naked eye might miss. Once, auditioning a young actor, I was watching him and was not much impressed. It felt like he wasn’t really committed. Perhaps it was just his inexperience. Then I glanced at my monitor, and WHAM! On screen he was fully present. The camera could see things the naked eye could not. It’s not really something you can learn in drama school. It’s a gift. Either you’ve got it, or you haven’t.

Sam’s got it.

Break a leg, Sam.

- Ian Mune's screen CV includes co-writing Sleeping Dogs, directing Came a Hot Friday, and at least 40 acting roles. His 2010 autobiography Mune includes index entries for Shakespeare, Sam Neill, Peter Bland and Ans Westra.

Sam, I have your iPod

By Roger Donaldson 05 Sep 2017

Sam, you have great taste in music — I must get your iPod back to you — the one you left at my place. It’s sitting in the docking station behind me and I love listening to your tunes when I’m typing away at my computer — like right now.

Okay, where do I fit into Sam’s life?

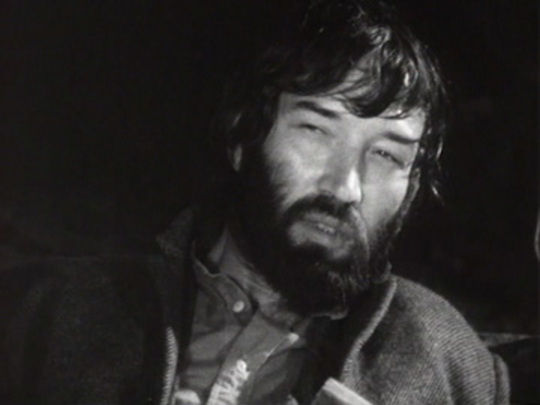

Sam and I go way back — way back!— back to the 1970s. I remember first seeing Sam in Barry Barclay’s short film Ashes, where he played a priest. Sam was so convincing, I really thought he was a priest — that I was watching a documentary, but no, it was Sam doing some very fine acting.

So fine, in fact, that I decided I would try and persuade him to be a part of my Smith’s Dream/Sleeping Dogs movie. My recollection is that I tracked Sam down and made contact with him — he was in Hong Kong. I remember Sam being bemused at the thought of taking the lead role of Smith in what was to be his first feature film, as well as mine.

Co-starring in Sleeping Dogs was American actor, Warren Oates. Warren was also impressed with Sam’s talents, and at the end of principal photography made no secret of the fact that he expected to see Sam up there on the big screen sometime in the near future. When Warren was saying his “goodbyes” to everyone, to Sam he said, “Sam — I’ll see you in the movies.” Warren’s prediction turned out to be spot on!

I believe Australian producer Margaret Fink saw Sam’s performance in Sleeping Dogs and was equally impressed. Sam took the leading role in her film My Brilliant Career that Gillian Armstrong directed, and Sam’s career was underway.

The English actor James Mason saw Sam’s fine work in this film and as a result, Sam finished up being cast as the lead in a high profile English production, Reilly: Ace of Spies. From that point on Sam’s career took a giant leap forward that saw him landing leading roles in major studio films like The Final Conflict, The Hunt for Red October and Jurassic Park.

Apart from the movies, Sam and I also share another passion: the wines of Central Otago. It was Sam that got me into the wine business. Sam has done an amazing job creating wine that has helped put Central Otago’s pinot noir on the international stage. His company Two Paddocks has gained an impressive international reputation for the wines Sam is making.

Not only are Sam’s acting talents superb, but he’s a fine looking dude, with a soft, silky, hypnotic voice — the man is as smart as a whip with a brilliant, quirky, self-deprecating sense of humour. Whenever I hear Sam make one of his memorable speeches, I am reminded how inadequate most are when it comes to public speaking, myself included…

Recently, I was in Auckland and Sam and I went to the Auckland Art Gallery to have a poke around; we also share a passion for New Zealand art. As we wandered from room to room, numerous women — some middle-aged, some young — spotted Sam, and followed him through the gallery. Sam seemed completely oblivious to this attention and I was reminded that Sam is a real star. When asked to pose for a selfie or sign an autograph Sam graciously obliged. It’s easy to forget what a luxury anonymity is.

Sam really should be called Sir Sam Neill — but Sam being 'Sam', he turned down the offer. That’s the sort of everyman Sam sees himself as, But Sam is no ordinary person, he’s fiercely pro New Zealand — a very committed supporter of the NZ Labour Party and a champion of the underdog. He’s also a major supporter of New Zealand arts, music, architecture and of course, Kiwi movies.

All this sounds a bit obsequious, I know, but you don’t often have the opportunity to publicly acknowledge how much you respect a lifelong friend. Sam, you have done an amazing job in your careers as an actor and in the wine business. Keep on truckin’ mate. Keep making those wonderful movies and fine wine, old boy — well done and Happy Birthday!

- Roger Donaldson directed Sam Neill in his breakthrough big screen role, Sleeping Dogs (1977). Since then Donaldson has directed movies in Los Angeles, London and Invercargill.