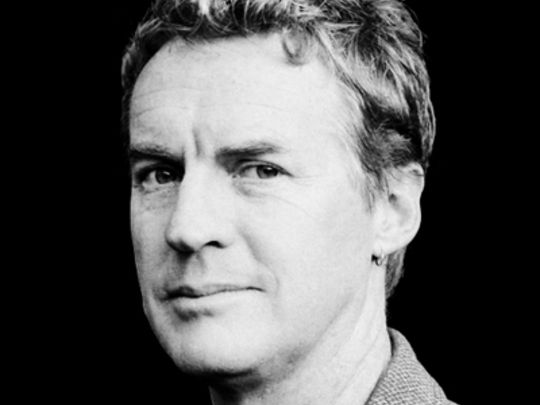

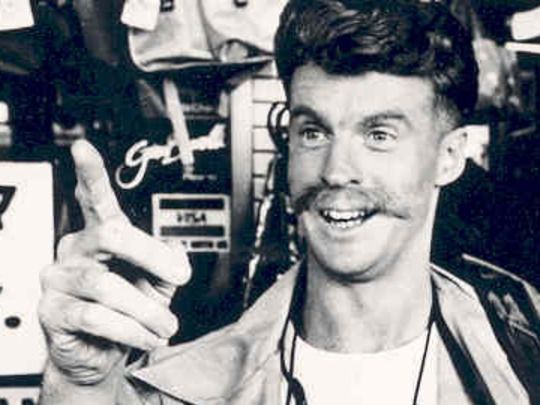

The Don McGlashan Collection

Small and useful things: the music of Don McGlashan

Don McGlashan likens songs to tools. “They are so small,” he once told writer Graham Reid, “and like any small useful thing they seem flimsy and lightweight but a lot of thought has gone into them. Like a lot of thought has gone into a really good kitchen knife or something made to be used.”

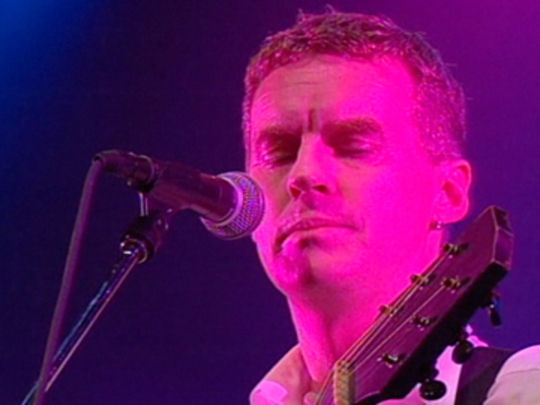

Over the better part of four decades, McGlashan has used those tools to build one of this country’s most serviceable songbooks. The songs are good for many different purposes: they have been played in concerts, movies, weddings, prisons, festivals and funerals. But they might be even more valuable for those smaller, invisible occasions, when you need to be reminded of a feeling, a person or a place, or just reassured that you are not alone.

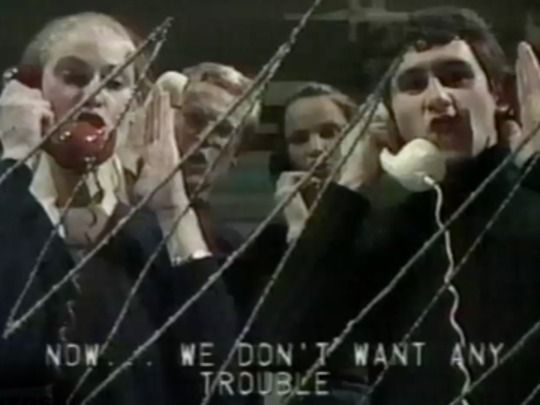

Though McGlashan has made music since childhood, it took him a surprisingly long time to focus his talents on those small useful things. At school in the 1970s he played keyboards in covers bands, and French horn and percussion in orchestras. In The Plague and the Whizz Kids he was a sideman, beefing up the ensemble on horn and percussion. For years he was a member of the experimental percussion/performance group From Scratch. Even in Blam Blam Blam, where he was first noted for songs like ‘Call For Help’ and ‘Don’t Fight It Marsha, It’s Bigger Than Both Of Us’, he was primarily the drummer, just one of three songwriter/vocalists.

It was only during his time in The Front Lawn, a multimedia collaboration with writer/actor/film-maker Harry Sinclair, that his destiny as a singer-songwriter really became apparent. Among the skits, dances, movies and assorted set pieces were some songs that went to places few New Zealand songs had been before. Ironically those were places in this country. But it wasn’t just hearing names like the Hutt Valley, Oriental Bay and Takapuna Beach sung for the first time. In ‘Tomorrow Night’ and ‘Andy’ universal feelings of belonging and loss were matched to stories so specific that it was the dual shock of being shown something new and yet recognising it immediately.

Since then, through The Mutton Birds and a series of solo albums, the songbook has continued to grow in depth and breadth: ‘Dominion Road’, ‘Anchor Me’, ‘Miracle Sun’, ‘Bathe In The River’, and dozens of others.

There are voices in these songs that come straight from that strange yet familiar landscape. There’s the particular kind of Kiwi male who will rhapsodise over the craftsmanship of a rifle (‘A Thing Well Made’), or marvel at a feat of engineering while struggling to find words for his feelings (‘Harbour Bridge’). There’s the laconic narrator of ‘White Valiant’, whose seemingly innocuous utterances (‘You’re from the family who moved in up the valley? It’s lucky I picked you up and not somebody else…’) are indefinably creepy when hooked up to that eerie guitar riff. And yet the voice becomes quietly eloquent in songs of love and gratitude like ‘While You Sleep’, ‘Anchor Me’, or ‘Lucky Stars’.

Is McGlashan this country’s Ray Davies, the Kinks’ leader and author of such quintessentially London songs as ‘Waterloo Sunset’ and ‘Lola’? Davies, for all his genius, never wrote orchestral scores, percussion opuses, theatrical sketches or anything as edgily abstracted as ‘Don’t Fight It Marsha, It’s Bigger Than Both Of Us’. Yet the comparison stands, not just for the way McGlashan, like Davies, fills his song with familiar yet seldom romanticised places, but that he has bonded those places to chords and melodies in a way that ultimately locates them beyond any map. In ‘Theme from The Lounge Bar’ McGlashan sang of a "chord-change that ‘makes the blood change direction in her veins", and his own songs can convince you they have that power. Track ‘Like This Train’, a sublime moment from The Mutton Birds’ Envy Of Angels album, is just one of many that seems to do that to me every time.

McGlashan often writes in character, yet in doing so frequently reveals his own moral outlook. While seldom overt or preachy (he expresses his aversion to "bad protest songs" in a revealing 2009 Talk Talk interview with Finlay Macdonald), he might be the most astutely political songwriter we have had. ‘Toy Factory Fire’ is told from the point of view of a company executive who justifies his actions to himself, as he conceals evidence of a criminal negligence. ‘Radio Programmer’ could be that dark song’s absurd twin, in which a deejay deliberates over whether or not to playlist the latest Don McGlashan single. But even in intensely personal songs like ‘Girl Make Your Own Mind Up’ and ‘Andy’, addressed to a daughter and a dead brother respectively, he slips in withering lines about trickle-down economics and the 80s property boom.

Though the prevailing tone of McGlashan’s writing might be described as one of hopeful melancholy, he can also be hell of a funny. The first time I heard the song ‘Marvellous Year’ (McGlashan performs it 18 minutes into this interview) was in a Grey Lynn backyard, at a launch for the album of the same name. The song culminates in a litany that intersperses landmarks in human progress with icons that have a special resonance in New Zealand. As I left the party, this new song still ringing in my head, I found myself talking to the musician Peter Urlich, who'd just come from the same event. Marvelling and laughing at what we had just heard, we spontaneously begun trading lines from the song. “The petrol engine, the old-age pension, the fire of Hades, the Briscoes lady, the Koran, the Torah, Interflora…”

The song borrows its title from Allen Curnow's poem The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch in which the poet, writing in the early 1940s, wonders what it means to be a New Zealander. In so many different and rewarding ways, McGlashan’s songbook, that kit of small and useful things, answers that question.

- Music writer and bass player Nick Bollinger is a reviewer for Radio New Zealand. He is the author of How to Listen to Pop Music, 100 Essential New Zealand Albums, prize-winning memoir Goneville, and an upcoming book on the Kiwi counterculture.