The Geoff Murphy Collection

The Geoff Murphy Collection

This collection has four backgrounds:

Magic hammers, and filmmaking by telepathy

Waking Sleeping Dogs

The Genius of Geoff Murphy

Lead trumpet for NZ film

Magic hammers, and filmmaking by telepathy

By Alun Bollinger 16 Sep 2013

Geoff Murphy and I got together to make films in about 1969. Geoff was still teaching at the time. He was a natural storyteller — a handy skill for a teacher to have — and was interested in telling stories on film. His appetite had been wetted by Derek Morton, who'd seen a play Geoff was doing with his class at Newtown School, The Magic Hammer.

Derek suggested they could make a film based on Geoff’s play. Geoff’s assumption, as a non-filmmaking teacher, was that Derek would bring a camera along to class one day, and they would make the film. But no...

Many months passed. They made costumes, built a camera crane, built elaborate sets out at Makara on Wellington’s west coast, and filming took place over many weekends. It was quite a mission, one which Geoff and Pat (Geoff’s wife at the time and mother of most of his children) had not foreseen. The Magic Hammer was never completed, but Geoff’s interest in moviemaking had been aroused.

One day I was shooting some footage with Derek Morton for a weekly kids’ show he made for television. A couple of Geoff and Pat’s children were in the cast, so Pat was there with the kids. I gather she saw me working and suggested to Geoff that he get in touch with me, which he did.

That was the start of a long collaboration between Geoff and I. I feel we developed an almost telepathic understanding of each other’s thoughts and ideas, but, having said that, it was an understanding based on many hours of creative conversation, plotting and planning for the many projects we worked on together over many years.

Our work together culminated with Goodbye Pork Pie in 1979.

- Alun Bollinger is one of New Zealand's most respected cinematographers. His credits include Vigil, Heavenly Creatures, Matariki and TV movie In Dark Places.

Waking Sleeping Dogs

By Roger Donaldson 16 Sep 2013

I consider Geoff a friend and a great filmmaker, and he has my utmost respect for his unique talents. He can be considered one of the founding members of the New Zealand film industry, and deserves recognition as a major figure in the local arts scene. Without Geoff’s tireless commitment to make true New Zealand films, there might not be the vibrant industry there is today.

Geoff is a director, scriptwriter, producer, actor, musician and special effects wizard, commanding enormous respect from his peers. He is a tireless, well-informed and outspoken advocate for respecting New Zealand multicultural identity — constantly reminding us why it is so important to have an indigenous film industry.

I met Geoff in the early 1970s and can honestly say that without the help and support he generously gave me, my early films may not have been made. Start Again (1972) has Geoff’s stamp all over it. Over the years he gave me generous encouragement and help with the Winners and Losers series, Sleeping Dogs, Nutcase and Smash Palace.

Geoff’s generosity to me over the years could not be better exemplified than when he helped with mounting one of my most ambitious projects, Dante’s Peak. When my son Christopher was running in the Olympics, Geoff came to Idaho and took over the reins of directing the movie for a few days, so I could take the time off to see Chris compete. It was indicative of Geoff’s generous nature that he would help me out like that.

Sleeping Dogs may not have been made without Geoff’s input — he helped with the script, with production, and did his magic on the special effects. His genius problem solving and lateral thinking made the film feasible. When it was impossible to import weapons into New Zealand for the film, Geoff said “no problem,” and set about building them. They fired electrically, and the flames that shot out of the barrels of the guns were created by exploding powdered match heads. That was Geoff at his best.

So many filmmakers in New Zealand in the 1970s, 80s and 90s had some help from Geoff.

Geoff is a pioneer in the integration of Māori and Pākehā culture in New Zealand cinema. Utu was a seminal movie. It explored the complex issues of New Zealand multiculturalism that few have been game to tackle in the way Geoff did. His film Goodbye Pork Pie is one of New Zealand’s most treasured.

Geoff is never one to step into the limelight, but he’s always present as one of the industry’s staunchest advocates, mentoring many young people into the business. He deserves our recognition for his service to New Zealand cinema, and his impact on our evolving cultural identity.

- Roger Donaldson is often credited with having launched the Kiwi screen renaissance with 1977 movie Sleeping Dogs. He has gone on to direct films about ageing motorbike racers, erupting volcanoes, and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Genius of Geoff Murphy

By Dominic Corry 16 Sep 2013

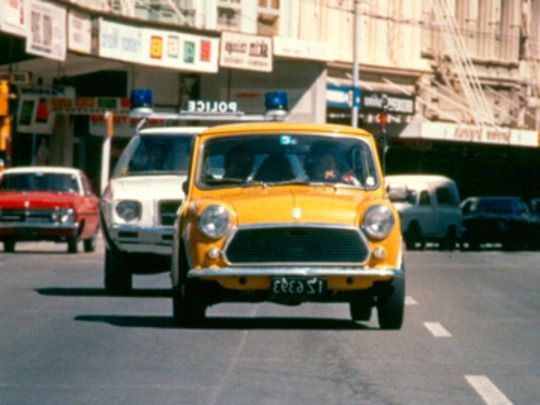

South Island. A remote West Coast road. The very early '80s.

Two endearing larrikins in a stolen yellow Mini speed pass a parked police car containing an officer and a lady friend locked in an intimate embrace.

"Is that cop pulling out?" enquires one of the larrikins.

At the risk of appearing to focus on the puerile, that line has always represented my experience of legendary New Zealand filmmaker Geoff Murphy. The joke was entirely lost on me when I first saw Goodbye Pork Pie. I was far too caught up in the non-stop popcorn thrills the film offered up. Plus I was nine-years-old.

In a sequence of events that applies to all of Murphy's major local works, I was only able to appreciate the splendidly lewd double entendre upon my second helping of Goodbye Pork Pie several years later, having matured enough to comprehend the delightful word play. It was also while revisiting Goodbye Pork Pie, and indeed all his films, that I came to fully appreciate just what Murphy brought to New Zealand cinema (apart from dodgy sex puns): an ability to wholeheartedly and successfully embrace genre without compromising the New Zealand context in any way.

His New Zealand feature films are amongst the most entertaining we've ever produced, and they all hit identifiable genre beats, but none of them feel anything less than 100% pure Kiwi. This ability to consistently fuse commercial filmmaking instincts with uniquely New Zealand stories is unmatched in our industry. It's understandable that many Kiwi filmmakers reject traditional genre tropes in the name of telling a 'New Zealand' story, but Murphy was always able to serve both ends, at the expense of neither.

It is perhaps ironic that New Zealand's first commercially successful film director mastered the skill in a context born entirely out of a decidedly non-commercial impulse to cruise the country in a bus with a bunch of mates, and play music, make films and put on shows. I am of course referring to Blerta — 'The Bruno Lawrence Electric Revelation and Travelling Apparition' — a collection of actors, filmmakers and musicians (usually all three at once) who went on to dance around the world and form the basis of the modern NZ film industry. From 1970 to 1975, Murphy, Lawrence and other notable friends fused music, live performance and film to the delight of audiences all around the country.

It's impossible not to draw a connection between this communal enterprise and the inherently collaborative nature of feature filmmaking. Plus the everyone-does-everything Blerta experience helped render Murphy a master of a huge variety of skills, both practical and artistic — a defining trait of the most assured directors.

A huge pile of the Monty Python meets Soul Train meets A Hard Day's Night material can be seen in the relentlessly fascinating full-length compilation, Blerta Revisited. Further insight into the Blerta days can be found in this episode of 1980s current affairs show Close Up.

Murphy's storytelling acumen can be easily identified in a notable pre-Blerta short, Tank Busters — a kind of proto-Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels effort from 1969, in which Murphy himself (looking like a handsomer George Harrison) commands the screen in a central role. Bruno Lawrence also appears of course — as 'Bruno'.

Going back even further, Lawrence, Murphy and co were clearly having a good time with the 1965 short film/music video Hurry Hurry Faster Faster. Lawrence incarnates 'Dr Brunowski', and Murphy propels the action at a footloose pace (a baton later picked up by The Front Lawn in films like Walkshort).

Murphy's first directorial brush with a wide audience came with the stunning, rarely-seen TV drama Uenuku, now available to view by the wider public for the first time since it was first broadcast in 1974. This groundbreaking adaptation of the Māori legend was the first TV programme to be broadcast entirely in te reo. It's a fascinating watch — Murphy ensures the storytelling sustains itself visually, and the whole enterprise (complete with vertiginous finalė) has the quality of a Māori-specific episode of the original black and white Twilight Zone. It's a spooky treasure.

Another often overlooked bridge between the Blerta days and the firecracker that was to be Goodbye Pork Pie is the 1977 Murphy-directed Wild Man. The ramshackle pioneer tale full of familiar faces (check out John Clarke's accent!) can be viewed in its entirety here.

Geoff Steven, a contemporary of Murphy's who directed the 1978 feature Skin Deep, charts this fertile period in his illuminating 1990 documentary Cowboys of Culture, carrying on through to the success of films like Sleeping Dogs, Smash Palace and of course Goodbye Pork Pie.

Sleeping Dogs got there first, Once Were Warriors got all the critical love, and more people have seen Whale Rider; but you'd be hard pressed to find anyone who would argue with the assertion that 1981's Goodbye Pork Pie is New Zealand's most iconic film. Murphy's crowd-pleasing filmmaking instincts were finely honed by the time Pork Pie hit. It easily functions as New Zealand's Bonnie and Clyde, Easy Rider, Jules and Jim, Smokey and the Bandit and Police Academy, all rolled into one. But it's also got an enduring anarchic flavour of its own that defies specific articulation.

The gender politics may be a little, er ... dated, but the entertainment value has remained wholly intact in the three decades since it was released, as has the sheer fist-pump-inducing fervour of its anti-authoritarian message.

A trailer, excerpts and a wealth of interviews with people involved in the making of the film can be found on the Goodbye Pork Pie page, none more entertaining than Radio New Zealand film critic Simon Morris' brief talk with the director. After Morris introduces their interview by presenting his articulate but lengthy summation of how Goodbye Pork Pie's underlying message was initially overlooked by the filmgoing public, the eternally laconic Murphy patiently awaits his chance to talk, then responds with: "Well I'm very pleased you brought that up. What was it again?"

Murphy's follow-up to Pork Pie was the ambitious historical drama Utu, which got renewed attention thanks to the release of a re-edited and remastered version known as Utu Redux. At the time, it was New Zealand's biggest ever local production, and the scale of the film can be easily discerned in Making Utu, a full-length look behind the scenes of the film from director Gaylene Preston (Mr Wrong).

Future Once Were Warriors director Lee Tamahori can be seen as the first assistant director, while the awesomely low-key Murphy looks like someone who wandered in off the street to see what all the fuss was about.

Although Utu is often cited as his masterpiece, Murphy's subsequent film is his defining work in my eyes. It currently stands as my all-time favourite New Zealand film. I'm talking about 1986's The Quiet Earth — an enduring sci-fi thriller with a reputation that continues to spread globally. There's even a reasonably popular sci-fi film website named after it.

No film better exemplifies Murphy's ability to tell propulsive, affecting genre stories within a New Zealand setting. This is a masterwork of its form in global terms, a haunting thriller that effectively harnessed the eeriness of going into central Auckland on a Sunday before 1990. For an insight into how The Quiet Earth (and Murphy's other works) were viewed compared to contemporaneous films, check out this 1987 episode of Kaleidoscope which looks at the boom in New Zealand filmmaking that followed 1977's Sleeping Dogs.

Murphy's next film would be his last downunder for a while. 1988's Never Say Die was a valiant attempt to mount an American-style 80s action film in New Zealand. The Temuera Morrison-starring movie isn't as well remembered as Murphy's other works, but I have a soft spot for it, and wish modern local filmmakers would attempt something with similar intentions. Along with 1985's Shaker Run, this comprises New Zealand action cinema's golden period.

Murphy's talents at this point took him to Hollywood, where he directed a string of efficient studio genre films, the best examples of which all had "two" in the title: Young Guns II, Fortress 2 and Under Siege II: Dark Territory — a criminally under-appreciated action thriller that stands as Steven Seagal's best ever film.

When Peter Jackson began mounting the Lord of the Rings trilogy in 1999, he wasn't about to let someone with Murphy's skills go to waste, and Murphy was employed as a second unit director. Murphy performed similar duties on American action film xXx: The Next Level; returning the favour to Lee Tamahori (who was Murphy's first assistant director on Utu and The Quiet Earth).

But Murphy wasn't done mounting his own movies, and in 2004 released Spooked. Officially a fictional tale, Spooked was inspired by events detailed in journalist Ian Wishart's book The Paradise Conspiracy. It's undeniable fun seeing conspiracy thriller tropes play out in a New Zealand context, and with its first person voice-over, jazzy score and shady shenanigans, it's possibly the closest thing we've ever seen to an example of Kiwi film noir.

It's been gratifying seeing the attention Murphy has been getting thanks to the release of Utu Redux. Even within the context of New Zealand's persistently problematic relationships with its major artists, it's hard to shake the feeling he is underrated [notwithstanding his 2013 Arts Icon Award].

Murphy's major works effortlessly straddle a line that every Kiwi filmmaker struggles with, and with them he played the largest single role in establishing what passes for a New Zealand cinematic identity.

If I was forced to look beyond the 'commercial-instincts-infusing-New-Zealand-stories' dynamic, and identify exactly why his films endure, I would say it's because they posed questions rather than provided answers. That kind of storytelling doesn't age.

It's an approach perfectly encapsulated by another (cleaner) quote from Goodbye Pork Pie, this one spoken by the immortal Bruno Lawrence as Mulvaney: "There's only one sure thing in life Blondini, and that's doubt. I think."

- Dominic Corry writes about film for The NZ Herald and Flicks, and is West Coast (of America) editor for website Letterboxd.

Lead trumpet for NZ film

By Derek Morton 23 Sep 2013

I'm very grateful to the cosmic lottery (or whatever it is) that arranged for my path to cross with Geoff's when I was 18.

Entering adulthood, people often discover others of similar outlook and inclination, to establish connections that can last for life. I hit a jackpot.

The anarchic, subversive and often outrageous approach that characterised the Victoria University jazz club clique immediately seemed like home to me, but I was only 'the kid' latching on to a group of musicians who already knew each other, mostly from Catholic schools. They were all slightly older than me, and Geoff was slightly older still. Whether because of that (married, with a baby and a respectable job) or just his natural organising ability, he always seemed to be at the centre of whatever was happening. And lots was.

I'd been playing around with 16mm film, but nobody else in that mob gave a toss about such things then. The next year Ian Mune and I shared a flat, and after I'd introduced Ian to the clique, some theatrical performance awareness began to infiltrate 'jazz club' activity (to emerge again much later via Blerta).

That same year Bruno and I ended up in Christchurch by accident (after quite a few too many while seeing some mates off to an arts festival on the inter island ferry) and in the course of various adventures there in the next few weeks I met my soon-to-be wife, so the wild underground lifestyle settled down. A bit.

Geoff and Pat and their children later bought a house in the dull suburb of Paparangi, and Di and I and our children were persuaded to buy one nearby. By this stage I'd had a full time 'day job' at WNTV-1 for some time, and had shot location film with young AlBol (at first based in Christchurch, later in Wellington).

It's true, as AlBol mentions, that I introduced Geoff to screen production (it took a while) but much of the innovation and creativity came from him, and his indefatigable approach meant that we took on logistic challenges that more cautious (sensible?) people would have shied away from: a huge interior set, a huge exterior set, designing and building equipment including lights, a dolly and tracks, a camera crane ...

That crane is usually confused in historical accounts with a later Acme Sausage Company one, but this was the first, knocked up with Danny, an Aussie welder, at Alliance Engineering, based on a cardboard model I'd made.

As with everything else, it got built because Geoff assumed that whatever we needed (even if the 'need' had only emerged as a rave from me about some grandiose shooting style a crane would allow) must be a possibility, somehow. And, as it turned out, it usually was.

Geoff's organisational and mechanical aptitude was vital (and anything involving explosions good fun) but the two key elements were his ability to gather people and make use of whatever talents and abilities they possessed, and his consistently fresh ideas for storylines and characters.

His patience when dealing with the worthy amateurs of funding committees, and his good grace while sitting through their sometimes nonsensical procedures, allowed larger productions to get up. Though support of Geoff back when support was needed was not always forthcoming, decades later it's good to see all now scramble to recognise him.

That he could get anything up at all while never holding a regular job in the screen production biz is testament to Geoff's persistence, plus his ability to rapidly comprehend whatever creative, technical and logistic details needed to be assimilated.

Even without the benefit of experience from a constant corporate production flow, he got on top of the process, and I observed his growing visual sophistication in off-work hours while hanging around on location for The Box, or pushing a car over a cliff at Houghton Bay for Tank Busters, or shooting rainbows for Uenuku.

Working within corporate television had its advantages. At a time when TV drama was a rarity, I got away with shooting a movie-length drama called Cereal (expanded from an original outline by, you guessed it, Geoff) as six episodes of about 20 minutes each — but only because it had been snuck into a children's series [Kid Set], and produced with the help of some dedicated crew, often working unofficially, plus 'jazz club' mates and the (by then) ASC crane.

When drama proposals had to be put up officially, such as a script developed from a James Cowan story (My Name is Mackay) that had been the subject of much late night raving with Geoff, the timid TV executives wouldn't have a bar of it. So it was very satisfying to see similar material eventually find its way to the big screen as Utu.

Goodbye Pork Pie drew in some very capable mates from other backgrounds to join the evolved 'jazz club' mob (by then the Waimarama mob): ex WNTV-1 (Mike Horton, Ian Paul) ex Pacific (Graeme Cowley, Mike Hardcastle) ex NFU (Don Reynolds, Sam Pillsbury) and ex Talking Pictures (Alister Barry), plus Annie Collins, Lee Tamahori, et al. But the energetic 'underground' approach remained unchanged.

I didn't see the Pork Pie shoot, being in the other hemisphere (though later entrusted with the international recut). But afterwards that able band, with a few variations, continued on gloriously, also overlapping into Roger's productions.

One day in Los Angeles years later I needed to get the signature of a Kiwi citizen for an official form. It asked "how long has the referee known the applicant" (the referee being Geoff) and "35 years" was filled in, followed by the thought "hey, that can't be right", but after a quick calculation, yep, it was. It's more than 50 now (and still, to 'the kid', unbelievable).

Back when I idly picked up Geoff's father's 8mm camera in the middle of the night at the Dominion pub (where we were all goofing around, stunned) to dream up an improvised Hammer Horror-style spoof starring Bruno in his first screen performance, the possibility that such nonsense could eventually lead to Utu would have seemed utterly ridiculous.

I should have known that with Geoff leading the charge — though battles may be tough — the goodies were always a good chance to win through.

- Australian-based Kiwi Derek Morton has been a cameraman, director (The Dominant Species, Roche) and writer (Carry Me Back). He has also run his own production company.