The Matariki Collection

The Matariki Collection

This collection has two backgrounds:

About Matariki

A Selection of Iconic Māori Programmes on Television

About Matariki

By Whai Ngata 04 Jun 2010

The term Matariki as we know it now is based on the appearance of the new moon after the helical rising of the constellation known as the Pleiades (a helical rising is when the constellation first becomes visible above the horizon). The first appearance of this group before sunrise signified the greeting, for Māori, of the new year. The festival to celebrate Matariki was a very important one in Māori eyes.

The New Year's Day was not fixed. It might occur in June or in May. In 2016 Matariki is celebrated on 6 June.

In the Far North, South Island and Chatham Islands the New Year was marked by the rising of Rigel in Orion. This does not make much difference to the date of the New Year. Note that stars in the constellations or the constellations themselves may not have been visible to coastal, inland, northern and southern tribes.

Matariki was not a time to plant, as I have heard many say (even at Te Papa). The harvests (such as kumara) were in and it was time to do other things. This played an important part for coastal dwellers as species of fish were seen to run at particular times of their lunar calendar.

The lucky or favourable times in the calendar were the fourth, 11th and 28th nights, with the most favourable period between the 23rd and 28th nights. Matariki was a time for learning (during the cold part of the year) and, because their enemies' storehouses were full of food, a time for war.

The main point to remember is there are many variations of the calendar and many ways the different tribes used stellar guides for their own specific environment. Given that, there are significant links in the calendars collected by the Dominion Museum from Māori and their related Polynesian cultures, the Moriori on the Chatham Islands, and those living in Tahiti, Hawaii and the Cook Islands.

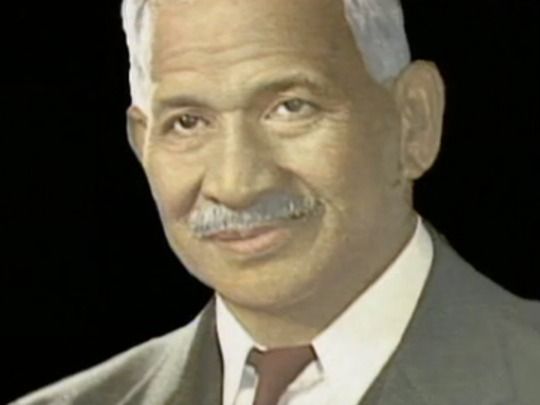

-Whai Ngata, ONZM, who passed away in April 2016, became a newspaper journalist after various jobs, including time on the family farm in Ruatoria. After seven years at Radio New Zealand, he joined Television New Zealand in 1983. Recruited by Ernie Leonard to help establish TVNZ's Māori Department, he would spend 14 years as its head.

A Selection of Iconic Māori Programmes on Television

By Whai Ngata 04 Jun 2010

During the first decade of television in this country, the Māori presence on our television sets was in the area of light entertainment. There had been a fairly liberal Māori presence on our screens as entertainers until a short drama series showing Māori in a real workplace situation in 1971. But really until until the Tangata Whenua series, the landscape was pretty much European.

This series was seen as a "window into the Māori world". It also provided urban Māori a spiritual re-engagement with their 'taha Māori' or their 'Māoriness'. After WW11, Māori trickled into the cities. By the 60s and 70s it had become a flood. This audience was to play an important role in the decades to come for Māori television.

Among the first to make their way into the cities were the 28th Māori Battalion men and their families. Three generations down they would start to lose their iwi and hapu identities. In 1980, when Koha went to air, there was a feeling of renewed ownership and pride in their Māori identity.

For Pākehā, Koha was a window through which the eye made connection (they may not have fully understood what they were hearing as many now-familiar Māori terms were not yet part of everyday New Zealand conversation). Māori felt a strong feeling of 'wairua' or spiritual connection, a feeling that multiplied many times over when they saw their own whanau or hapu on screen.

That wairua — which can also be very critical — grew stronger when Te Karere, the first regular Māori language programme went to air during Māori Language Week in 1982, then became a regular part of the TV schedule in 1983.

In 1985, a group called the Māori Broadcasting Association urged TVNZ to give the Māori Production Unit, (which then came under 'Special Projects') the same mana as other production departments. Hugh Rennie, chairman of the TVNZ Board, said at the end of a three page letter, "I assure you and your members of our commitment to succeed in the development of Māori programming in this country."

The independent Māori production houses were a product of the late 80s and 90s, with many of the company principals coming out of the department that was formed the next year, in 1986. As producers became more proficient, some were able to bring in extra sponsors for parts of the shows we were making. In the 90s they used this confidence to begin to form their own companies.

Protest was a strong part of the process which saw Māori language progress in statutes, in broadcasting and education. Land issues and their environment also played an important part for iwi. The early Māori broadcasts were expected to give an understanding of what was being said; they provided a Māori perspective that may have been lacking in the years before.

The setting up and the launch of Whakaata Māori or the Māori Television Service was a huge milestone for Māori, one which was seen by many as one of the 'taonga' that would help with the protection of the Māori language and tikanga. Many court sittings, The Waitangi Tribunal and a lot of agitation by Māori finally led to a Māori Television Service actually getting to air on 28 March, 2004.

Five years on, the government has received a report suggesting amendments to the Act that enables the channel to operate. Among the suggested changes is to give the service an obligation to strengthen the processes that not only protects te reo, but gives voice to the Māori people.

-Whai Ngata, ONZM, who passed away in April 2016, became a newspaper journalist after various jobs, including time on the family farm in Ruatoria. After seven years at Radio New Zealand, he joined Television New Zealand in 1983. Recruited by Ernie Leonard to help establish TVNZ's Māori Department, he would spend 14 years as its head.