The Tony Williams Collection

The Tony Williams Collection

This collection has three backgrounds:

A convention challenging career

An Interview with Tony Williams

Michael Heath on collaborating with Tony

A convention challenging career

By Lindsay Shelton 17 Nov 2010

Tony Williams' reputation as an innovative and imaginative director is built on a unique series of documentaries which he made for New Zealand television in the 70s, and on his persuasive and memorable commercials. He directed two features, industry frontrunner Solo in Wellington at the end of the 70s, and cult horror Next of Kin in the early 80s, after he had moved to Australia.

He was one of a group of inspired filmmakers whose careers were made possible by the encouragement of pioneering Wellington producer John O’Shea. “John fired my passion for film and became my mentor,” wrote Tony, who borrowed a film and camera from O’Shea to make his first short film, The Sound of Seeing, soon after leaving Hutt Valley High School.

The 1963 non-narrative film shows the different ways that an artist and a composer are inspired by objects and events. A year later, O’Shea ended up giving him the job of director of photography for the 1964 feature Runaway, and he also shot O’Shea’s Don’t Let It Get You in 1966. He and camera assistant Michael Seresin were “barely past their 21st birthdays,” wrote O’Shea in his memoir.

In 1967, Williams received an Arts Council scholarship to study cinema at UCLA; then he moved to London, working as an editor, including helping make two documentaries — Takis Unlimited (1969) about a sculptor, and Sound The Trumpets Beat the Drums (also in 1969) about a music festival in Iran hosted by Empress Farah and the Shah.

His return home, enthusiastic about the new wave of BBC television films being made by directors such as Ken Russell and Ken Loach, was well timed — years of pleading by John O’Shea had persuaded New Zealand television to reverse its closed-shop production policy and to offer a chance for independent documentaries. The films which Williams directed were the highlights of what O’Shea (who produced all of them) described as “a few short glorious years of television documentaries.” For those of us who remember the amazement of discovering them on television, they stood out as astoundingly different from the formulaic daily programmes.

The first was about service clubs, a subject in which television’s staff directors had no interest. With Tony directing, beginning a series of creative collaborations with playwright Michael Heath, Getting Together (1971) became not only “a catalogue of Wellington eccentrics” but also “a celebration of people who create any excuse to combat loneliness.” The film won the award for best television programme of the year, “which really put Television One’s nose out of joint.”

The collaboration continued with even more extraordinary results. The Day We Landed on the Most Perfect Planet in the Universe (also 1971) was a hymn to juvenile freedom, starring a class of Petone 11-year-olds. “I wanted to avoid attempts to analyse, rationalise or make judgements … rather it was free-flowing extemporised observations that came from the children’s own imaginations, with stimulus from their fictional teacher played by Michael Heath.”

The Unbelievable Glory of the Human Voice (1972) is a memorable exploration of the history of singing. For ‘If I Loved You’, the filmmakers got together as many singers as they could find, to sing the song in their own style, and then cut them together. Michael Heath appears in drag as Dame Florence Foster Jenkins, who hired Carnegie Hall for a concert, though she couldn’t sing. The final four-minute history of rock music uses a montage of thousands of stills. Extraordinary!

Each of Tony Williams’ documentaries challenges conventions.

In Deciding (1972) the unscripted subject is conservation. A fisherman is trapped in a labyrinth of government departments when he tries to find out why the fish have died in his local river. Peter Fyfe plays the fisherman. Everyone else is a real person, mainly public servants who were embarrassed to see themselves when the film was telecast.

Take Three Passions (1972) combines sport, art and science. The three men defending their obsessions are musician and choirmaster Maxwell Fernie, amateur astronomer Peter Read, and journalist Terry McLean. (He was “rhapsodising about rugby,” said O’Shea.) Williams filmed their pub debate with three cameras, and then used the art of editing to integrate all three passions.

Logistics were the challenge for Rally (1973) made with 16 cameramen including Roger Donaldson, Leon Narbey, Graeme Cowley, Alun Bollinger and Waka Attewell; Geoff Murphy worked on car rigs. The rally covered the North and South Islands – Tony controlled his crews from a helicopter.

The Hum (1974) was about yachtsman Geoff Stagg and his boat Whispers in the race from Wellington to Picton. Tony was on board with O’Shea’s son, cameraman Rory O’Shea. There were cameras in three chase boats, and Steve Locker-Lampson filmed from a helicopter. Producer O’Shea said the film captured the essence of an off-shore race.

1975 saw Tony Williams, Michael Heath, and mates get Lost in the Garden of the World (1975) at the Cannes Film Festival as they discover an event and a world which none of us at home knew anything about. They showed prescience in their choice of emerging filmmakers, interviewing Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, among others.

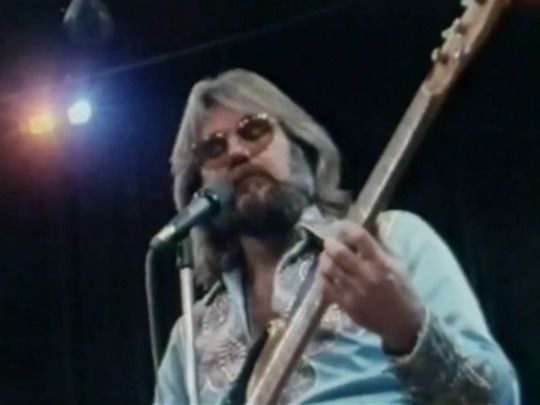

Tony Williams’ other documentary from this period was Rolling Through New Zealand, featuring Kenny Rogers and the First Edition. Another logistical challenge.

In 1975 he formed his own production company and two years later he started Solo, his first feature, with a budget of $140,000 and a script which he co-wrote with Martyn Sanderson. His Australian-shot feature, cult horror film Next of Kin, was another collaboration with Michael Heath.

His three decades of iconic commercials include Coke’s Sky Surfer which screened in 150 countries; SPOT for Telecom, featuring the tireless eponymous dog; the MASH-aping charm of Dear John, advertising BASF tapes; and possibly most famously the Cadbury Crunchie Bar gold rush promo, with a who’s who of 70s Kiwi acting talent having a rollicking time on a runaway train playing out a hammy western plot. In 1999 came the Bugger commercial, in which a dog has almost the last word.

In the same year he made one more documentary – Before the Operations Begin – about a middle-aged search for adventure in the South Pacific, for Australia’s ABC television.

- Lindsay Shelton spent over two decades in film distribution for the New Zealand Film Commission. He handled sales of over 60 features, including Goodbye Pork Pie, An Angel At My Table and Once Were Warriors. He is now the editor for current affairs website Wellington.scoop which he co-founded in 2008.

An Interview with Tony Williams

By Tony Williams 17 Nov 2010

Recorded on 11/10/2006

How do you see the Director’s role in making a commercial?

Experience has taught me a director has two responsibilities. The first is simply to translate a client’s idea into a piece of entertainment that will capture the attention and the hearts (if you’re lucky) of the public. The second responsibility is to the producer: to complete the shoot on time and on budget. A ‘People’s Choice’ award is for me far more significant than an industry award. It tells me I’ve done my job. The industry can get very hung up on its own ego and naval gazing, but we are simply story tellers.

When I was asked to make the Hyundai Restless (Baby) commercial, I made it clear the success of the ad hinged on the casting of the baby, rather than what I could do with special effects. Without the baby the ad shouldn’t be made. After exhausting the casting budget in Wellington and Auckland, I had no significant shortlist to offer Assignment’s Howard Grieves and Kim Thorpe.

It was getting tense, time was running out, but there was no child I was prepared to put my name to. My producer Maggie Lewis asked for more time, and more casting budget to hold sessions in Australia. At this stage, many other agencies might have asked to see all the casting tapes we had. But I have always had a terrific relationship of trust with Kim and Howard, and they dug deep and came up with the extra casting funding.

We went to surfboard city in Queensland and discovered Dante. Within seconds of seeing his test tape, I knew he was the one. I rang Maggie and said ‘we’ve got him’.

The same thing happened on the Toyota Bugger ad. We looked in Wellington, Auckland, Melbourne and Sydney. Time was running out once again. There were many actors who could have handled the role, but there was only one man who made me laugh. Without him, it wouldn’t have been the same ad. We found him at the last moment.

When did you begin making commercials and how did your career progress from there?

That’s a scary question. In the early 60s I actually worked as an assistant on the very first ad ever made for television in New Zealand. It featured a well dressed gentleman [Peter Harcourt] walking into a bank, and all his clothes suddenly pop off to reveal him standing with nothing on but Jockey underpants. It was banned. So we had to go back and reshoot the jockeys as a matte – the man disappears and the jockeys stay on screen on their own. It was tough learning how to do a matte on our first ever commercial.

I became a DoP, shooting a couple of early feature films with John O’Shea at Pacific Films. Mike Seresin was my focus puller. In the late 60s Mike and I went to the UK. He became a DoP and I went into editing, working initially at the BBC as an editor, then free-lancing on movies and commercials. Then I began to direct. I returned to NZ and rejoined Pacific Films and made a series of ads for Greggs coffee — Different Faces, Different Places — which was fairly unique in its day. We shot documentary cinema verité style in the streets with real people and available light.

Mid 70s I set up my own production company and the Great Crunchie Train Robbery was our first ad. We produced it out of my living room on a budget of about $15,000. A good friend of mine was Martin Scorsese’s editor in Hollywood, and he talked some major studios into letting us use footage from studio feature films at a very low cost. Crunchie must have become the longest running ad in Australasia. Unfortunately, the budget was very tight and as I had gone over budget and I couldn’t pay myself. However, Roger Macdonell took pity and gave me a Masport motor mower as a thank you. That mower became my fee.

The industry at this stage was made up of a few production companies who owned their own equipment and employed the crew on staff. I was keen to start a freelance system going, and Geoff Dixon was heading in the same direction at the same time.

So Geoff and I found a little old house in Oriental Bay Wellington. It was pink so we called it ‘The Pink Palace’. Geoff stuck a desk in one bedroom and called himself Silverscreen, and I took the other bedroom and called myself Tony Williams Productions. We jointly set about persuading film technicians to leave their permanent job and become freelance. And so our first freelance DOP was John Blick, who also took a bedroom at the Pink Palace and with Norman Elder set up New Zealand’s first lighting and grip company with one Bedford van called Filmobile.

Don Reynolds was our sound recordist and mixer and Pav Govand became New Zealand’s first freelance gaffer after we wrestled him out of his salaried job at the National Film Unit. Initially I edited all my own commercials but as things became busy, Pat Cox set up the first independent editing company in New Zealand and handled all of Geoff’s and my work. They was pioneering times!

In 1979 I was asked to make the Dear John BASF commercial for a retail offshoot of Colenso – it was strictly retail in budget so we were able to tack it on the end of a major Colenso shoot for BNZ. Art Director Ron Highfield had no money to create a set which was supposed to be somewhere between Vietnam and the Second World War, so at midnight he ‘borrowed’ a pile of Wellington city council 44 gallon drums, silver caps were removed from milk bottles (before dawn) to become dog tags for the soldiers, Italian Fishermen in Island Bay temporarily misplaced their fishing nets as they become camouflage nets on our set. It was hairy going, but it won best ad of the decade in Australia in 1990.

In 1980 I moved to Australia to make a feature film and in the early 80s set up Marmalade Films with Fred Schepisi, Robert Le Tet and Maggie Lewis. This finally became the Sydney Film Company with Maggie and myself .

How much change have you seen in commercial filmmaking over the years?

In shooting – very little, other than bigger crews. But in post production enormous changes. There was a time we had to shoot our own supers and mattes ‘in-camera’ – winding the film back and double exposing the image. Then we progressed to the Oxberry printer at the National Film Unit. We would sometimes wait two weeks to see a simple end super put onto a pack-shot – and the answer prints were made on 16mm, often burnt out and lacking definition.

Today’s post production techniques are awesome. Not only what the post production houses have to offer, but homework that a director can do with tools on a good laptop. I was recently on a ship on my way to Tasmania, and was able to supervise post production on the Bulls commercial for Toyota Hilux at the same time. I sat on deck, powerbook on my lap connected to the net by mobile phone, using Final Cut Pro, Adobe Photoshop and a digital camera to communicate notes and ideas to all the creative boys at Oktobor who were animating the Bulls. All that has only been possible in the last few years.

Other changes? Sadly a lot of trust and loyalty has gone out of the industry. There was a time when the client trusted the agency, and the agency trusted the filmmakers. Mutual respect made for some fabulous team work and great ads. In the early days in Wellington, working with creatives in Saatchis and Colenso was like being part of an extended family.

So looking back, what would you say is the winning recipe for great ads?

It hasn’t changed from the 60s to the 2000s.

1. Great ideas. Generally the simple ones are best.

2. Great casting. Don’t settle for second choice if a bit more money will buy better talent.

3. Trust. The clients must trust the agency. The agency must trust their director. If you don’t trust each other, don’t work together.

4. Styles, techniques and fads come and go. But good story-telling wins the hearts of the public - hands down every time.

5. Make ‘em laugh.

Michael Heath on collaborating with Tony

By Michael Heath 17 Nov 2010

1.

It was the early 70s, and Wellington's two ‘bug houses‘ — the Roxy and Princess on Manners Street — were churning out a parade of endless B-movies, noirs, westerns, horrors, and crazed Filipino war movies. Myself, and friends Peter Herbert and Mark Spratt, seemed to spend our days and nights inside these dark, dank, cat-piss-smelling palaces of wild and lurid dreams, amongst drunks sleeping off their indulgences. Little did we know that five years later the three of us would be rushing around Cannes making a film about some of our favourite directors (Herzog, Speilberg, Scorsese etc).

I was balancing a job of proof-reading for NZ Truth, helping with the running the Victoria University Film Society (it was DW Griffiths, Fritz Lang, Eisenstein, Pudovkin in those days!), writing film reviews with Nevil Gibson and Rex Benson for student rag Salient ... and decided to go for an audition for an acting role for a bank commercial that was being held out at Pacific Films. I met Tony Williams, John O'Shea and his team for the first time. Tony was a fun, approachable person who had just returned from working on exploitation films in the US, and in France with Alain Resnais, and also in Iran, and in the UK where the documentaries of the wonderful Ken Russell were shocking the nation.

I was vulnerably impressed, and excited by all of Tony's exploits and I remember that we shared a passionate love of cinema straight away. Not only commercial, mainstream fodder, but cinema from different cultures, with different styles of cinematography and editing, that broke all the rules.

For the ad I was dressed in dowdy farmer's clothes, with a silly hat, and they had set up a swing in the studio. I acted, and sang like a complete idiot, while they filmed me. What was really disconcerting was that everyone began pissing themselves with laughter so much I got the commercial, and so my marginally non-existent career began. In those days black and white television had a series called Survey, and Pacific Films were involved in making some of the most truly outrageous, and memorable social glimpses of that period.

Getting Together(1971) was the first film we did, and I experienced the bliss of true collaborative filmmaking with friends for the first time. The film still evokes an innocent time, with bizarre, and eccentric people with extreme obsessions — from the Flying Saucer Club, with its members who looked like they staggered out of an Edward D Wood film — to the highly-suspect but enthusiastic thespians of the Peter Pan Players, with their memorably incoherent melodrama How now Hecate. There was a wonderful freedom about this style of filmmaking that I have tried to retain to this day.

The largest work was The Day We Landed on the Most Perfect Planet in the Universe (1971) with my friend Robert Lord, who taught at a school in Petone. I was to play the teacher, and the film was a free-wheeling fantasy based on the imagination of children. I was also required to play the piano, and improvise scenes with the kids. Perhaps the most wonderful moments in this film take place out at Paekakariki on the beach, when the teacher is liberated from the constraints of the classroom, and leads the children out into a vast, natural world of freedom. We used the music of Georges Delerue here (whom both Tony and I loved), and I find these scenes very moving to look at still, as I ended up living by this same coastline in Raumati South.

2.

In 1972, Tony was shooting The Unbelievable Glory of the Human Voice. I had played Tony a recording of the ‘Queen of the Night’ aria from Mozart's Magic Flute, by the bizarre and highly-untalented Florence Foster Jenkins, and he asked me if I would like to impersonate her. This was shot in the Wellington Town Hall the day before I left for London. As well as coping with enormously-unmanageable strapped-on angel's wings, I also doubled as the accompanist, and this sequence still amuses people to this day.

During my years away, Tony and I remained in contact, and even though I immersed myself in watching, and studying films at the National Film Theatre, I had not started to write yet, despite a few monologues for theatre and some radio plays as a beginning. NZ still did not have a film industry, and I decided on the documentary idea of a group of Kiwis visiting the Cannes film festival, talking to filmmakers, actors, and directors, that might give some impetus to the Government at the time to set up an organisation to make New Zealand films.

Through John O'Shea, Pacific Films, and a commission from TVNZ, along with an interested television channel in the UK which would provide seedling money, Tony would fly to London to team up with us, and then we would head on down to the South of France in a kombi van. Disaster struck when the English Producer from the Television Company committed suicide by jumping off an inner-London building roof, just as Tony arrived to start pre-production.

Our seedling money was gone, and so through the miracle of bank cards Tony managed to get his cast and crew together, and we set off on our journey to pick up a camera (from Michael Seresin in Paris), and then drive all the way down to the South of France, shooting en route. It was a heady, mad time — as we basically winged it in every way possible, and through sheer Kiwi ingenuity, managed to secure our wondrous cast of young film directors, and an actor — Paul Bartel, Tobe Hooper, Werner Herzog, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg and Dustin Hoffman — who thought we were extremely unusual, down-to-earth and likeable in the way we approached them.

Tony and I had no idea what film would come out of this and we improvised every moment of it. It is was only later when we began editing back in London, when John O'Shea arrived to overlook the completion of the film, that the themes of the film emerged very strongly, and on being able to secure wonderful ‘clips’ we decided on the title Lost in the Garden of the World (1975).

There are many stories about what happened next: TVNZ banning the film, demanding cuts, then re-instating them, and eventually passing the film uncut for broadcast; but whatever happened the film still exists. It has been available to be screened at the NZ Film Archive (on request), turned up on Film Society's programmes, and is now available online courtesy of NZ On Screen to delight future generations of filmmakers.

John, his family and Tony were my main mentors, all through their lives, and I feel that perhaps it was serendipitous that we met when we did, as we all shared a love of world cinema, and tried through our work to show this love with films that stand the test of time, and hopefully will remain in their own small way a contribution to our film culture history in New Zealand.

Addenda:

Both Mark Spratt and Peter Herbert, who were on the crew of Lost in the Garden of the World, continue to work in the film industry. Peter is the curator and manager of the Arts Project in London, and Mark runs an Independent Film Distribution Company in Melbourne.

- Writer, Director and Producer Micheal Health’s contributions Kiwi cinema cross many genres, including the children’s vampire tale Moonrise/Grampire and the nostalgic chiller The Scarecrow. Heath has worked on several films with long-time friend and mentor Tony Williams.