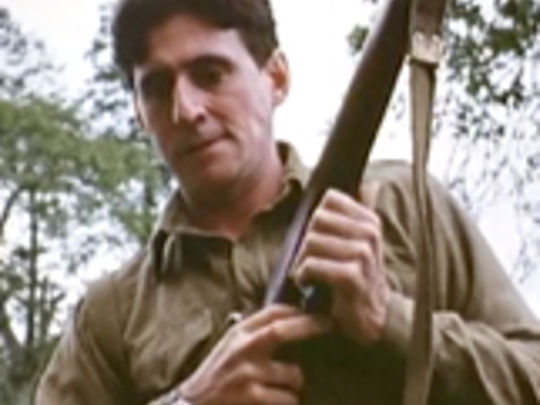

John McKay

John McKay is a veteran sound editor, sound designer, and mixer. He abandoned an early focus on directing to build a diverse, respected career in post-production. His credits include significant contributions to iconic films The Quiet Earth, Footrot Flats, Kitchen Sink, and Lord of the Rings. McKay is notable for an approach which combines creativity with a high level of technical craft and organisational rigour.

The worst thing you can do is just put your hand on the last thing that worked. I have always run on instinct – all my best moments have been mistakes or things done by chance, that I then recognise and explore. John McKay

The Rule of Jenny Pen

2024, Sound Design - Film

Coming Home in the Dark

2021, Sound Editor, Sound Design - Film

Lowdown Dirty Criminals

2020, Supervising Sound Editor - Film

The Turn of the Screw

2020, Executive Producer, Supervising Sound Editor - Film

Helen Kelly - Together

2019, Sound Mix - Film

Births, Deaths & Marriages

2019, Sound Designer - Film

Wellington Paranormal

2018 - 2022, Supervising Sound Editor - Television

Loading Docs 2016 - Same But Different

2016, Sound Design - Web

Pot Luck - Series One

2015 - 2016, Sound Edit Supervisor - Web

3 Mile Limit

2014, Sound Editor/Supervising Sound Editor - Film

Romeo and Juliet: A Love Song

2013, Sound Design, Sound Editor - Film

Gardening with Soul

2013, Sound Designer/Sound Mix - Film

Shopping

2013, Sound Editor - Film

Fresh Meat

2012, Sound Editor - Film

Netherwood

2011, Sound Mix - Film

Bogans

2004, Sound Mix - Short Film

Kombi Nation

2003, Sound - Film

Back River Road

2001, Sound Editor - Film

Crooked Earth

2001, Sound Designer, Sound Editor - Film

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

2001, Sound Mix - Film

Jubilee

2000, Sound Designer/Sound Mix - Film

Lawless: Beyond Justice

2000, Sound Mix - Television

Lawless: Dead Evidence

2000, Supervising Sound Editor/Sound Mix - Television

Magik and Rose

2000, Sound Design, Sound Mix - Film

What Becomes of the Broken Hearted?

1999, Sound Designer, Sound Mix - Film

Lament for Barney Flanagan

1998, Additional Sound Mix & Sound Editing - Short Film

City Life

1996 - 1998, Supervising Sound Editor - Television

Peach

1995, Sound Editor/Sound Re-recording Mix - Short Film

Plainclothes - First Episode

1995, Sound Mix - Television

Riding High

1995, Supervising Sound Editor - Television

Fallout

1994, Sound Editor - Television

Fallout - Part Two

1994, Supervising Sound Editor/Mixer - Television

Fallout - Part One

1994, Supervising Sound Editor, Sound Mix - Television

Marlin Bay - Series Three, Episode 11

1994, Sound Mix - Television

Bradman

1993, Sound Mix - Short Film

Deepwater Haven - First Episode

1993, Sound Mix - Television

Marlin Bay

1992, Sound Mixer/Supervising Sound Editor - Television

Moonrise (aka Grampire)

1992, Supervising Sound Editor - Film

The End of the Golden Weather

1991, Sound Editor - Film

Star Runner - First Episode

1990, Sound Mix - Television

Star Runner

1990, Supervising Sound Editor - Television

Piano Lessons

1990, Sound Mix - Short Film

Raider of the South Seas - First Episode

1990, Sound Editor - Television

User Friendly

1990, Sound Effects Editor - Film

Zilch!

1989, Sound Editor - Film

A Soldier's Tale

1988, Supervising Sound Editor - Film

Rushes

1988, Sound Design - Short Film

Hey Paris

1987, Sound Design - Short Film

Starlight Hotel

1987, Supervising Sound Editor - Film

The Making of Footrot Flats - The Dog's Tale

1986, Subject - Television

Bridge to Nowhere

1986, Supervising Sound Editor - Film

Footrot Flats - The Dog's Tale

1986, Sound Design - Film

About Face - Universal Drive

1985, Editor - Television

The Quiet Earth

1985, Sound Editor - Film

Death Warmed Up

1984, Sound Effects Designer - Film

Heart of the Stag

1984, First Assistant Director, First Assistant Director - Film

The Lost Tribe

1983, First Assistant Director - Film

Pheno was Here

1982, Editor - Short Film

Flight 901 - The Erebus Disaster

1981, Sound Editor - Television