The first of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The second of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The third of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The fourth of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The fifth of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The sixth of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The seventh of seven parts of this full length documentary.

The credits from this documentary.

Architect Athfield

Television (Full Length) – 1977

A Perspective

Note: this piece is taken from the 'Nine Documentaries' chapter, written by Russell Campbell for 1996 book Film in Aotearoa New Zealand.

During the 1970s there was a rebellious spirit abroad at the National Film Unit. Several directors broke away from the mould of tourism promotion which, as in the period prior to 1940, had again become the dire norm of government film making. Paul Maunder, for example, moved into the dramatised documentary with strong elements of social criticism (Gone Up North For A While, One Of Those People that Live In The World), and otherwise violated conventional publicity-film expectations (the deglamourised Games 74, which he co-directed and edited, provoked howls of outrage from the public).

Other directors, while sticking with straight documentary, took advantage of the new flexibility, which shooting on 16mm gave to make films which were more intimate, informal and personal than anything which had previously come from the NFU.

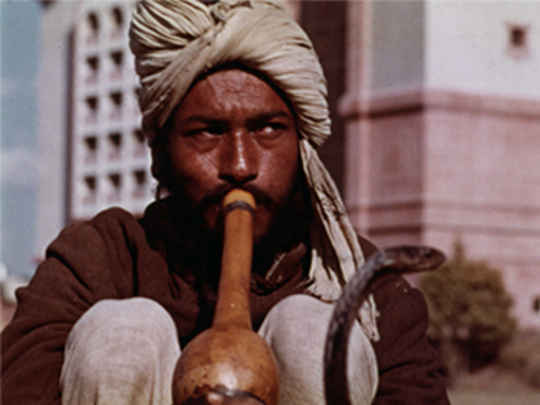

One such production is Sam Neill’s Architect Athfield (1977). It is a portrait of the innovative architect and his work both in Wellington and in relation to his award-winning design for community urban redevelopment in the Philippines. What is immediately apparent — after a long prologue documenting the existing living conditions in the Tondo squatter area of Manila — is the relaxed rapport which the filmmaker enjoys with his subject.

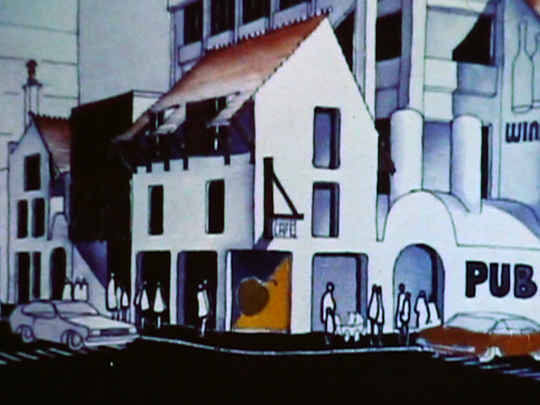

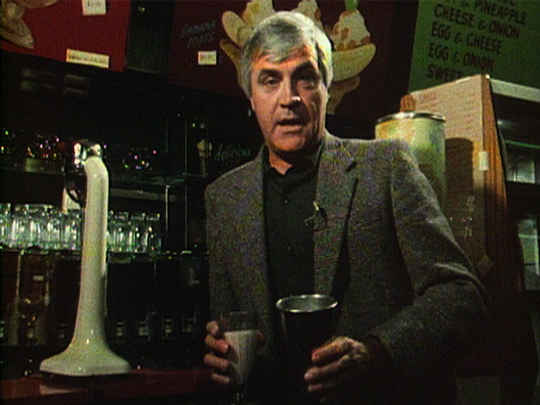

Asked, "What would you like in a film about you?" the architect replies: "I really don’t know . . . I suppose being with the people, some sort of physical contact, ah, drinking, laughing . . . " (The director will oblige with a sequence shot in the pub after work.) When Athfield gets tongue-tied as he is about to launch into a discussion of his high-rise projects, he says, "Oh look no, you’ll have to start me off again," and instead of cutting out this subsequently supplanted Take 1, the editor leaves it in.

The advantages of being freed from the cumbersome 35mm gear which NFU crews had had to work with in the past, in the days when virtually all their productions were aimed at cinema release rather than television, are evident in the free-flowing handheld camerawork of much of the film. This is particularly striking in the cinéma-vérité style of Athfield’s visit to the Tondo (when he chats with the local people who may be relocated into the new urban village he has designed for them if the Philippines Government ever gets around to building it).

The laid-back spontaneity matches Athfield’s personality, and also captures a certain quality in his design work. Throughout, the visual approach accords with the subject: for example, a nice conjunction of images occurs when the film cuts from a shot of a pot created by Athfield’s client Neville Porteous, a form characterised by tubular accretions and excrescences, to an aerial shot of an Athfield house with just the same characteristics.

An appealing, offbeat character with scraggly long hair and bermudas, Athfield is presented as an imaginative architect critical of orthodox Kiwi design and planning (like the standardised suburban sprawl of state-house Porirua), a provocateur whose work provokes aggressive reactions (Porteous remarks: "I think we live in a community which is particularly hostile to change, and perhaps even to originality"), a thinker whose Third World housing project encompasses a whole range of social and economic considerations (centring on local control) way beyond the aesthetics of design.

Yet there are some other opinions. Architect Miles Warren suggests that the forms of an Athfield building may be imposed from outside rather than derived from its function, and comments that the "extraordinary wit and amusement" which his former employee brings to his design work is a dangerous quality: "What is amusing one year is a bore even a year later." And without naming names, sociologist Alan Levett speaks of a group of "selfish professionals", architects among them, who service an élite clientele and "have added to growing inequality in New Zealand by their orientation to marketplace demands."

These comments are explored no further, not thrown at Athfield to respond to. Yet they are remarkably corrosive. Given that the traditional NFU film offered an account of the world which, like most products of the public relations business, excluded contradiction and conflict, what is most novel about Architect Athfield is perhaps not its camera style, its informality or its somewhat iconoclastic subject, but simply that at the end it leaves a question mark hanging.

- Russell Campbell is an author, academic and filmmaker, whose books include Observations: Studies in New Zealand Documentary. This excerpt is taken from Campbell's chapter 'Nine Documentaries', found on page 105 of the 1996 edition of Film in Aotearoa New Zealand (Victoria University Press), edited by Jonathan Dennis and Jan Bieringa.