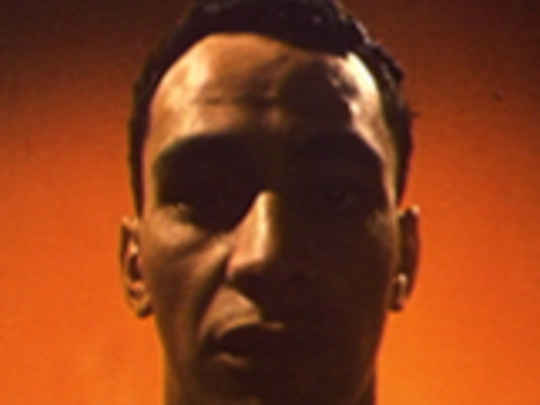

Barry Brickell: Potter

Short Film (Full Length) – 1970

A Perspective

"I make these sculptures because they're abstract forms related somewhere to organic shapes . . . they are exercises in form. Purely form. Very little else. This is what excites me, making new forms bring together images that have never been seen before. Perhaps they are a kind of anthropomorphic engineering that has grown out of being of the Pacific — open, generous and abundant." So said potter Barry Brickell in the programme for 1992 ceramics and glass exhibition Treasures of the Underworld.

Lynton Diggle's award-winning National Film Unit short features Brickell at work on the Coromandel Peninsula. It was here he developed his two great interests into lifelong pursuits — ceramics and rail.

Brickell established himself in the Coromandel in 1962. He had moved there the previous year to teach at the local high school, but by year's end he recognised that teaching was not for him. Instead Brickell threw himself into full-time ceramics production — and the development of a narrow gauge railway on the property, to help him shift clay and sculptural pots, between his studio and the kiln.

Government policy of the day aided this choice. British art historian Peter Tomory (quoted in Christine Leov-Lealand's 1996 book Barry Brickell: A Head of Steam) describes the context: "Barry and his generation benefited in enormous measure from the [1950s Finance Minister Arnold] Nordmeyer so-called ‘black budget', for it banned all imports except those of general need. This included the banning of all overseas domestic and decorative ceramics." People turned to locally-produced ceramics, and Brickell was able to sell enough work to live off.

Ceramic artists in New Zealand largely had to find their own way. Available technical information focused primarily on British and European resources, and wasn't necessarily applicable to New Zealand conditions. Starting in the late 1950s, Brickell built his own pottery wheels and kilns, and always erected one wherever he lived. He also travelled around the country (by rail) helping other artists set up their kilns — notably fellow contemporary ceramicists Yvonne Rust and Helen Mason — and could always be relied on to help out.

Brickell was also an early innovator in the ceramics field. His work combines whimsy and levity with complex technical knowledge and ability, and his forms developed into something completely original. In her book 100 New Zealand Craft Artists (1998), Helen Schamroth argues he brought "integrity and adventure to the whole craft scene" in New Zealand. At the time this film was made, Brickell was already exhibiting his work regularly in the four main centres.

Rail was Brickell's other great love — his fascination for furnaces and steam engines dated back to his childhood. He founded the NZ Society of Potters in 1963, and in 1966 the NZ Railway Preservation Society. The Coromandel railway featured in this film was the prototype for what became the famous Driving Creek Railway, established on 24 hectares of land nearby. Brickell bought the larger piece of land in 1973, and began building the narrow-gauge railway. It has since become something of a tourist attraction in the area. Brickell passed away in January 2016, at the age of 80.

Barry Brickell: Potter was one of a number of short films on New Zealand artists made by the National Film Unit in the early 1970s. It won an award from the Educational Film Library Association in the United States, and a Mercury Film Prize in Italy.

- Mary-Jane Duffy has written for magazines (The Listener), museums (Te Papa) and art galleries. She wrote an arts column for Wellington magazine FishHead, and now works at workplace development council Toi Mai.