Charlie Horse

Television (Full Length) – 1978

A Perspective

It is only a little over 30 years since this oddly affecting little documentary was made, yet it already feels like a relic from an ancient time.

This impression is heightened by the weathered texture of the 16mm celluloid medium, which has faded to a dirty monochrome. Mouldy blotches and crackly sound also add to the notion this movie wasn't so much made, as found in an attic somewhere.

Martyn Sanderson was a vital part of the extended family of Blerta creatives who set themselves up in a loose commune at Waimarama Beach in the 1970s.

Assisted by some of the other residents, notably cameraman Alun Bollinger, Sanderson documented his vexing experiences breaking and training a young horse named Charlie. Derek Morton, Geoff Murphy, Annie Collins and Pat Cox are credited with helping Sanderson with the edit.

The breaking-in process was not terribly successful. Charlie was eventually sold to owners better suited to handling him. To try and make something of all the film he'd shot, Sanderson screened a mute rough cut to locals at the Waimarama Marae Social Club, and made audio recordings of their reactions.

Essentially then, Charlie Horse is a home movie, with narration spliced together from live commentaries.

Some film historians have tagged the film experimental; whether this is so is debatable given the largely straightforward breaking-in story. Either way, TV documentaries sure as hell don't look like this any more. Amazingly, the film was produced for TV One, with initial funding from the Arts Council.

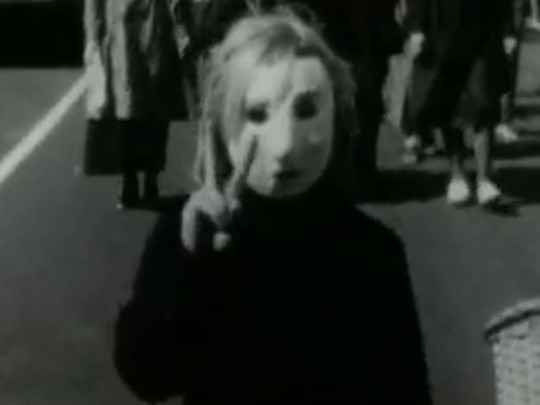

Charlie Horse exerts fascination through the simple power of its narrative and there is some haunting imagery. As we watch an animal being castrated and hobbled, a little voice on the soundtrack says, "some people don't know that animals have feelings..." The counterpoint of a horse breaker's casual cruelty, with a child's commentary is almost unbearably poignant.

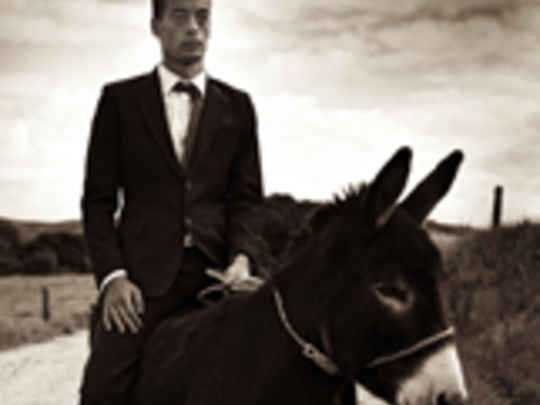

Beyond summing up the fate of one horse, Sanderson perhaps unwittingly makes a bigger statement about the quixotic aspirations of the Waimarama commune. A subtext of paternalism, and even contempt can be detected in the attitudes of the Hawkes Bay locals against the hippies in their midst.

Sanderson's failure to ‘break' Charlie was probably inevitable. He's too much of a romantic. Too ‘soft'. One can see that in his images of Charlie hobbled, dejected and pathetic. He revels instead in pictures of the horse running wild and free after breaking loose.

The too vast distance between the commune's idealised view of country life and the pragmatic outlook of seasoned rural dwellers is summed up in the horse breaker's parting shot, "animals are clever. They can abuse kindness, or ignorance. Charlie did that".