The director's perspective

Working with Hone was a blast. I stayed friends with him for the rest of his life, and he certainly enriched mine — and thousands of others through his words — and deeds.

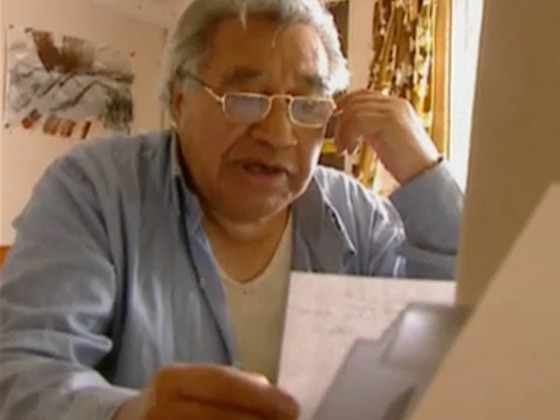

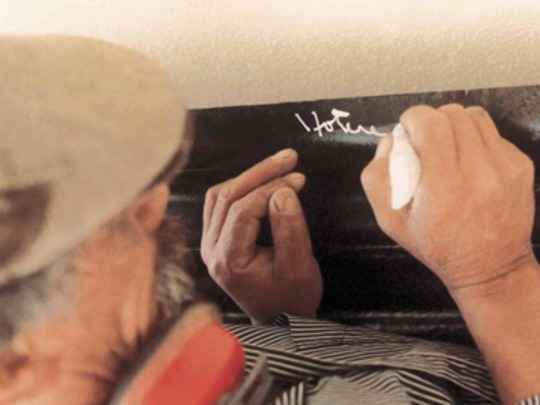

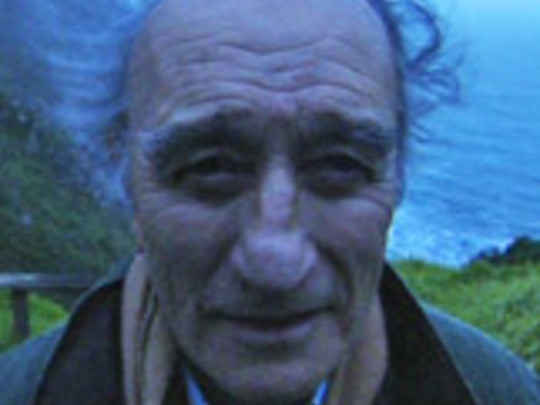

I like the bit in the film where Hone put on his straw hat, and carted us off to film him at the government offices in Balclutha. He told us he wanted to be filmed in front of a tapestry a friend of his had made for the wall there. What he was really doing, was making sure the IRD ladies were going to do his tax return for him, so he wouldn't have to pay any! The wily old cove maintains he hasn't got school certificate maths (true) and implies he is a helpless old man (not true).

He showed us many masks as we travelled around with him. I think that is what makes the documentary so agile — you can't cut Hone straight. He must go round. He didn't want to talk about the past. When [Tuwahre's biographer] Janet Paul saw the film, she thanked me for it and made the comment that Hone wasn't good at talking about the past. "Emotional amnesia," she said.

One of the things I love about making documentaries is how one can travel so completely into someone else's world. I was lucky with my team — Mark Derby, Simon Reece, Brian Shennan, and Alun Bollinger.

Hone knew AlBol's father Max, from their days as [Communists] Comrades. Hone naturally ganged up with AlBol to resist my plans, but by day two he was amazed at how compliant AlBol was. "She's pretty bossy," Hone told him, "She bosses you around." AlBol emerged from behind his camera and cheerfully agreed. "Yeah, she's got much better at it."

Glenis and Norm (the diary owning couple featured in the film) looked after Hone until the day he died, well after they had sold their dairy. Norm would take him his newspaper and get him up in the morning — lots of jokes. When I arrived to see him just before he died, Norm went over to tell him I was there, and Hone was still in bed. "Tell her to f**k off," he told Norm, but when he was reminded I had two fat muttonbirds with me, he said, "Goodness gracious! get me up!"

- Gaylene Preston directed Hone Tuwhare, and other things besides.

Back to top

A perspective

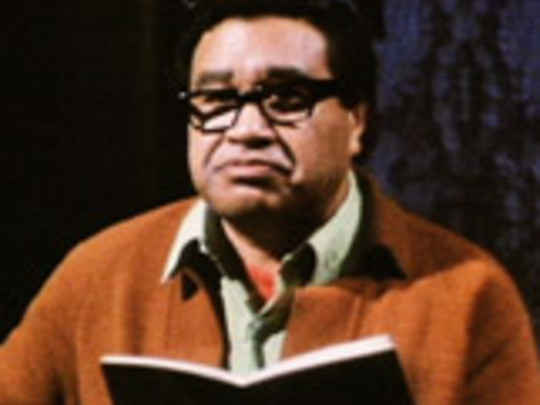

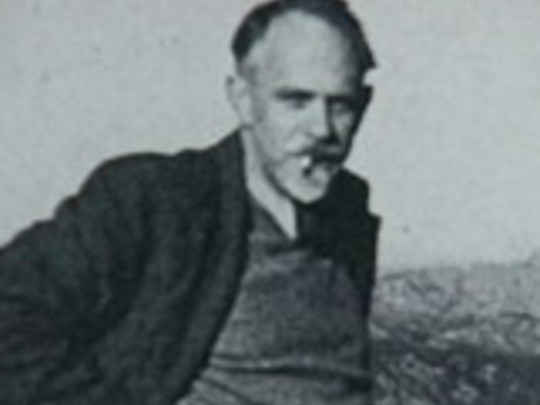

Hone Tuwhare (1922-2008) — much-loved poet laureate (New Zealand's second), Māori, socialist, boilermaker, local character, sly shit-stirrer — has been described as, "New Zealand's most distinguished Māori poet writing in English" (Terry Sturm in the Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature). His well-known poems, particularly No Ordinary Sun, with its earthy articulation of nuclear horror, are taonga of New Zealand poetry. He is one of the handful of New Zealand poets to have a recognised public persona.

Tuwhare spent his final years in a tiny house in the South Otago settlement of Kaka Point, and in 1996 he allowed director Gaylene Preston and a film crew to observe him at home, and travelling the country reading his work. The result is this punchy, warts and all film. It screened as part of TV One's Work of Art series, and snares Tuwhare's colourful character and his lifelong fascination with words.

As Janet Hunt describes in her book Hone Tuwhare - A Biography, for him "words are musical notes of bells, of nose flutes. They are the rattle of milk bottles in crates, the hiss of tyres on a wet road, the stir of trees creaking in a storm." The readings recorded here capture Tuwhare's unique synthesis of Kiwi vernacular with the oratorical.

Old friends, colleagues and neighbours give their impressions of Tuwhare and Preston allows him to speak for himself, even to the point where he, typically, subverts proceedings.

There are lovely moments in this documentary, including a subtly hilarious bit of tomfoolery which underscores both the film's achievement, and the difficulty of Tuwhare as a subject. I can speak about it with some authority, as I was there. The occasion was the videotaping of a short item about Hone Tuwhare for TV3 arts show, Sunday. I was the director, and I was there with a camera crew, and presenter Kerre Woodham. Preston had asked if she could shoot the filming, as part of coverage for this documentary.

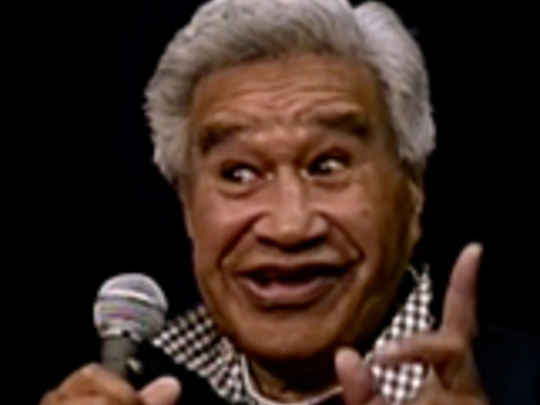

What I found interesting and highly amusing at the time, was the way in which Tuwhare immediately subverted the conventions of this exercise. He largely ignored poor Kerre, instinctively playing instead to the largest audience he could see — which was our combined camera crews. Of course, by doing this, he swung his eyeline away from our presenter.

Looking for less of a profile shot, my cameraman crabbed sideways to adjust his point of view. We all followed: director, sound recordist, and presenter. Behind me, Gaylene and company did the same thing. All of us were magnetically attached to Hone Tuwhare's chin. Did he realize what was going on? I think so. He proceeded to switch his eyeline back and forth, forcing us to pedal gently from one side of him to the other.

Preston captures the whole silly charade. It's funny, but also makes an important point. Like many New Zealanders, Tuwhare was not fond of talking about himself in the abstract; but he was a terrific performer. Give him a stage, a lectern, or even a modest green school desk, and he could go off.

One on one, he could be a difficult subject. Preston chooses her moments carefully to either surround him with an active context — doing things natural to his routine — or capturing him in the act of creation and performance. He had a wicked wit, and a rare talent for combining lofty thought with down to earth connections. The film is alert to the smallest introspective bon mots. Unlike himself, says Tuwhare, Shakespeare would not rhyme the word 'allegories' with 'groceries'.

Preston and her longtime collaborator, cinematographer Alun Bollinger, stretch out and make full use of the opportunities afforded by the poet's environment for capturing some strongly iconic rural imagery — shots that perfectly complement the man's words.

- Costa Botes has directed many documentaries, including portraits of poet Sam Hunt (Catching the Tide) and novelist Michael Morrissey (Daytime Tiger).

Back to top