Making Utu

Making Utu is Gaylene Preston's documentary about the making of 1983 movie Utu (directed by Geoff Murphy). Preston doesn't impose any narrative on the footage, but simply observes the goings-on of the production and captures Murphy's motivation for filming the story.

An opening title, "100 years ago is today — the past is the present — the future is now", makes clear Utu's consciousness-raising ambitions, and hints at the undercurrent of unease that has existed between Māori and Pākehā. This unease was particularly felt during the time of Utu's 1982 production, in the wake of the 1981 Springbok Tour protests and the arrests at Bastion Point.

Making Utu explores the kaupapa behind the movie. It includes interviews with Joe Malcolm, Utu's cultural advisor, while Murphy, casting director Merata Mita and actor Martyn Sanderson share their understanding of the story's exploration of New Zealand's racial past.

Back when Utu was made, few films in New Zealand's relatively brief screen history (with notable exceptions, such as Rudall Hayward's Rewi's Last Stand, and TV epic The Governor, made six years before Utu) had openly explored the effects of colonisation, negative or otherwise.

Utu's way into the New Zealand land wars was to look at the motivations and actions of individuals on the frontier of history, where "the good guys aren't necessarily the boys in blue and bad guys aren't always in harakeke skirts".

As Merata Mita remarks in Making Utu: "we [still] have Māori fighting Māori, we have Māori fighting Pākehā, we have Pākehā fighting Pākehā ... it's very hard to draw the line." Sanderson remarks that the film "will inevitably be seen as symbolic of the whole land wars, the whole relationship between Pākehā and Māori at that time". Even so, the filmmakers are up for the challenge, and the documentary shows director Murphy's willingness to front up to history.

There's almost an activist zeal behind the project — understandable, given that much of New Zealand's history was not being taught in schools (kings and queens from England still reigned). Many of the Land Wars stories had been preserved in the Māori oral tradition but, aside from academics, weren't widely known amongst a mainstream Pākehā audience. Historian James Belich's influential The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1986) had yet to be published, and the major TV series based on the book was still 15 years away.

Mita said in a newspaper interview at the time: "we still regard our [New Zealand's] history with a sense of shame. Otherwise things wouldn't have been kept hidden for so long". So Utu was a frontrunner for getting these stories — our stories — out there. In the doco, there's a strong sense of the mission Utu bears ,and Murphy is a stickler for respecting cultural sensitivities. Preparing to shoot a tangi he notes that "there's no point showing it, if you show it wrong".

After the breakthrough success of Murphy's previous movie Goodbye Pork Pie, expectations were high. Murphy and his Swannie-clad crew not only had to be faithful to culture, they were also keen to deliver a blockbusting good yarn. The ambitious melding of big themes with the genre demands of a big-screen action film made Utu something of an aspiring 'Once Upon a Time in the South', and resulted in unprecedented production demands.

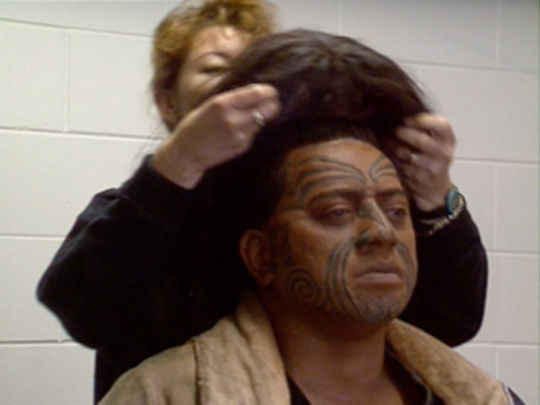

In Making Utu scenes from the finished film are included, and Preston deconstructs how they were made. Young assistant director Lee Tamahori is seen staying calm under pressure, and the art department make cardboard hats with spray-painted badges for the British militia. Tā moko artists etch tattoos on Zac Wallace (starring as Te Wheke), and there's the filming of the infamous "What's the time Mr Wolf" scene, where Te Wheke beheads the vicar (Martyn Sanderson) in a church.

Large scale action scenes set amongst steep central North Island bush and on the volcanic plateau are rehearsed, with actors, extras and explosions all wrangled into order. Actor Kelly Johnson cajoles a horse to move, with a little less assurance than he managed with Goodbye Pork Pie's yellow mini. A nice time-lapse shows the resourcefulness of the production crew as a house is burnt down, trucked away, then reconstructed as a pub in another location. Corralling it all is Murphy: candid and wry, inevitably with a ciggie hanging out of his mouth, grinning at the chance to pull it off.

Without commentary, the mood and energy of Utu's creation is captured effectively. Making Utu screened on TV in early 1983. Director Preston later recalled that it "went down surprisingly well with the general population, who, as it turns out, don't mind if there isn't an actual linear story".

It's compulsive stuff, and a valuable study of the challenges of shooting of a endemic epic in the 1980s — on the same rugged terrain where in the 1870s New Zealanders were shooting each other.

[Additional writing by Paul Stanley Ward]

Back to top

Utu

If there was a renaissance, or 'new wave' of New Zealand filmmaking, then Geoff Murphy was riding it; and ride it he did, tall in the saddle with this vastly ambitious, but sometimes vexing ‘puha western'.

The film's antecedents are clear. Murphy wears his love for Sergio Leone's spaghetti westerns, and the countercultural attitudes of 1970s Hollywood cinema on his sleeve. But the cultural markers of NZ history poke through all the same, and give the picture a defining sense of uniqueness.

Released in 1983, when memories of Bastion Point and the Springbok Tour were fresh, Utu's mix of unresolved colonial conflict and Murphy's energetic direction promised to be as potent as the quadruple-barreled shot-gun Williamson (Bruno Lawrence) brandishes in the film.

The zeitgeist was ripe for a revisionist, genre-challenging epic made from our own muddy, blood-stained whenua. After the one-two punch of Murphy's Goodbye Pork Pie (1981) and Roger Donaldson's Smash Palace (1982), there was a palpable air of expectation. The indications were that this was going to be a breakthrough picture.

It had scale, action and adventure, played out in the wild places of the volcanic plateau; a big rich symphonic score, composed by John Charles, and performed by our very own national orchestra; it had a bunch of well-loved Kiwi thespians, led by the immortal Bruno Lawrence, who revels in the role of the avenging farmer. Most of all it had Anzac Wallace — union delegate-turned-actor (starring as guerilla leader Te Wheke) — and what an impact he made in his sporadic career.

There's much to like in the film, starting with the raw subject matter — which was inspired by real characters and events. A church scene where a Vicar loses his head, and the attack on the Williamson farm are both outstanding sequences, showing what Murphy was capable of. There is great energy and flair in the action scenes.

In The New Yorker, legendary critic Pauline Kael gave Utu an extended rave. She praised Murphy as a filmmaker with an eye for "a deracinated kind of hip lyricism", and argued that he seemed to be directing with a grin on his face. Wrote Kael: "We know this basic story of colonialism from books and movies about other countries, but the ferocity of these skirmishes and raids is played off against an Arcadian beauty that makes your head swim".

There are also moments of Murphy's trademark laconic humour, for example when a post-coital Kura (Tania Bristowe) remarks "didn't you say your gun could fire seven times without stopping?"

Utu's scale is impressive and Murphy crams it all into lavishly shot and composed scenes: threatened frontiersmen, disgruntled natives, lusty wahine, bible-bashing priests, idealistic upper crust officers and traitorous kupapa.

Murphy's work had always existed in the space between popular film genres, and a specifically Kiwi sensibility. But for the first time, he arguably failed to bridge the gap. Utu's shotgun approach to the great New Zealand (colonial) film ultimately leaves the narrative feeling episodic and tangled in the supplejack.

Yet, despite local critical ambivalence, the New Zealand public responded well; for a time it was Aotearoa's second highest grossing film after Murphy's Goodbye Pork Pie. Utu's revisionist take on 'The New Zealand Wars' helped rewire popular perceptions of our history, thanks partly to complexly motivated characters (where the good guys aren't necessarily the boys in blue, and the bad guys aren't always in harakeke skirts).

Roger Horrocks later wrote that although it was an uneven film, Utu "succeeded in stirring up more discussion of New Zealand history than any recent book has done."

Utu was the second Kiwi film officially invited to Cannes (out of competition in 1983; The Scarecrow had been invited to the Director's Fortnight the year before). Variety reviewed it promisingly: "Murphy has produced powerful images and strong performances. Action sequences, special effects, and visual exploitation of a rugged, high country location in central New Zealand are superb ..."

In early 1984 Utu producer Don Blakeney asked Murphy to recut the film to make it "more accessible", arguing that a big sale to France hinged on doing so. The recut has been referred to as 'The Director's Cut', although Geoff Murphy had nothing to do with it, and later regretted allowing it to happen. In a 1985 interview for Onfilm magazine he remarked: "I declined to recut it myself because I was absolutely exhausted and saturated with it. I couldn't face it."

The film was shortened by almost 20 minutes, and the final fireside court martial scene intercut throughout the narrative. The consensus on this cut is that it is tidier, but lacks the personality of the original version.

It would be years until others seriously essayed the territory of the colonial wars. Unfortunately, Vincent Ward's River Queen walked into some of the same holes. The challenge of large scale period recreations on low Kiwi budgets, and of reconciling story conventions with a sense of historic truth that's both respectful and accurate, remains unfulfilled.

Nevertheless in Utu there is a true raw excitement to be had in the risk; at seeing on screen the archetypes of the Western turned to post-colonial New Zealand themes for the first time. It is passionate filmmaking, and with talents like Murphy, Lawrence, Cowley and Wallace firing, a propulsively engaging attempt.

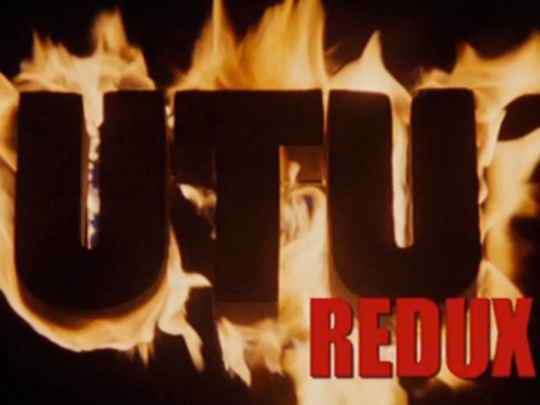

Thirty years after its initial release, Utu Redux introduced the film to a new generation of Kiwi cinema-goers. In 2013, the "enhanced and restored" cut, produced by Utu cinematographer Graeme Cowley with Murphy and editor Mike Horton, premiered on the opening night of the Wellington leg of the NZ International Film Festival, and won rave reviews.

The programme guide to the Festival touted the relevance of this "elegiac, absurdist vision of the devil's spirit in paradise", with the final campfire scene speaking "more clearly than ever to a New Zealand audience now".

Said Geoff Murphy in 1982: "When you make a film about racial conflict, you are living dangerously. When you make a film about racial conflict in a country that congratulates itself on what a successful bicultural society it is, the danger heightens."

Note: This piece was originally written in 2008 when clips from Utu were first uploaded to NZ On Screen. It has since been updated by NZ On Screen.

Sources include

Roger Horrocks, 'Moving Images in New Zealand' in Headlands: Thinking Through New Zealand Art. Editor Mary Barr (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1992)

Pauline Kael, State of the Art: Film Writings 1983-1985 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1985)

Geoff Murphy, A Life on Film (Auckland: Harper Collins Publishers, 2015)

Roy Murphy, 'Film Maker's Philosophy' (Interview with Geoff Murphy) - Onfilm Magazine, 1985

'Variety Staff', Review: Utu' - Variety, 31 December 1982

Back to top