Moriori

Television (Full Length Episode) – 1980

This title has two backgrounds:

Moriori

I believe that one of the most creative elements of Moriori is the beautiful and haunting soundtrack, written by Sir William Southgate. He used voices singing in the Moriori language to create music that conjures up beauty and bleakness, happiness and despair, horror and tragedy — but offering no note of hope. That’s because what happened to the Moriori offered no hope. Tommy Solomon, the last full-blooded Moriori, died in 1933. The race was declared extinct.

Our dramatised documentary revealed the history of the Moriori race, up to that point in time (1979). But it also offered some slivers of hope. We took two members of the Solomon family living in Temuka — Tommy’s descendants — on a pilgrimage to trace the ancestry they knew very little about. Brother and sister Charles and Margaret Solomon are 25 per cent Moriori. Their journey through this documentary was the flame that rekindled the renaissance of a race of people, once numbering around 2000, that had lived peacefully for centuries among their subtribes on \ in The Chatham Islands. This utopian existence in a harsh land was destroyed with a terrible massacre and enslavement in 1835.

Behind the scenes on 1980 documentary Moriori. All photos supplied by Wayne Tourell

This is the story that writer/producer Bill Saunders asked me to direct for him in 1979, for Television Two. We were a good team, having made many documentaries together.

Bill’s great, great grandfather Samuel Deighton was appointed as magistrate to the Chatham Islands in 1873. In 1889 he wrote and published A Moriori Vocabulary; hence Bill’s knowledge and interest. Academics and anthropologists had investigated and written about the Moriori story for many years, and archaeological digs had excavated ancient villages revealing Moriori life on the islands, over the centuries. Yet it seemed to have remained purely as a documented history — one that had never been fully revealed or appreciated by general New Zealand. That is until Bill and researcher Julienne Stretton did a bit of digging of their own.

Filming at the Moriori village. Graham Smith is behind the camera. Director Wayne Tourell sits to his right, with his arm out, then sound recordist Rod Wilson (standing), writer/ producer Bill Saunders (in white) and Margaret Solomon, a grandchild of the last full-blooded Moriori.

We filmed most of our interviews and dramatic reenactments on the mainland, before flying to Rēkohu. Margaret had never flown before. Sitting in a container with windows, which itself sat inside the rumbling bumblebee of a Bristol freighter, probably wasn’t the ideal introduction to flying. The twice-weekly flights were the islands' major link to the mainland, but the plane's limited payload meant we had to spread our crew, equipment and sets out; it took a week or so to get sorted as a complete production unit. We also had a replica of a waka kōrari — a Moriori wash-through raft — built for us by Murray Thacker from Okains Bay Museum.

We were a crew of 12, shooting on 16mm reversal film. We shot on board the plane, and during the heartfelt welcome Margaret and Charles got from their extended family upon landing. It was the first time they'd met some of their relatives, and the first time they'd set foot on their ancestral homeland.

Charles Solomon Rehe and Margaret Solomon (Margaret Hamilton) in the Moriori village. Margaret passed away in 1997.

In those days The hub of Chathams social life was the only hotel on the islands — in Waitangi, the main settlement and fishing port. There was very little transport, few rental vehicles, and apart from one road in Waitanga, all roads were unsealed. Our unit manager Doug Hamilton had managed to cobble together enough assorted vehicles to get us everywhere we needed to be —hopefully! So our first meeting with many of the locals was at the Waitangi Hotel. A warm party atmosphere — lots of good cheer, singing and raucous laughter — seemed to set us off on the right foot with the Chatham Islanders. We'd been warned some were not happy with the telling of the Moriori story. We didn’t feel any animosity that night.

Auckland Museum anthropologist Dave Simmons had given Margaret and Charles a 1923 book by Dr H G Skinner. It was the definitive history of the Moriori civilisation. Skinner dispels many myths and stories about who the Moriori were, and their origins. The book became a valuable guide to Margaret and Charles on their journey of discovery. Following the pair — mostly shooting from the hip, in real time — was our task. The Solomon whānau accompanied us on most of the journey; their knowledge helped us enormously.

While we were filming the documentary side of the story, our designer Mark White and his crew built a working Moriori village. It replicated one excavated a few years earlier on an archaeological dig by Doug Sutton and his team from Otago University. All that work and expertise would later be burnt to the ground for the cameras.

The Moriori village recreated on the Chatham Islands, including a replica waka kōrari— a Moriori wash-through raft.

Then unusual things started to happen. A Land Rover was rolled (but nobody was hurt). Minor accidents happened to crew. Some became ill. One had to be returned to Christchurch. We were told that a tapu had been placed upon us by a small faction of disgruntled Islanders. Charles arrived on location one morning a little battered and bruised, after an altercation in the hotel the night before.

However the majority of islanders were very cooperative. In the dramatised scenes, they played everything from village families, to slaves working kūmara gardens, and dead bodies. They couldn’t do enough for us. For example, I desperately wanted a tracking shot from the point of view shot of a swan in flight, during a scene of a stick game. There were no professional dollies [a wheeled platform used to capture moving shots] available. So what did Mark and the islanders scrounge? A couple of lengths of railway line and an old railway jigger, complete with bogey wheels. Presto: a brilliant tracking platform, albeit a heavy one that took lots of manpower to set up. I used it a lot.

This camera dolly (moving platform) was made from old railway lines and a railway jigger found on Rēkohu.

The most frightening and dangerous part of filming was a boat trip to the Sisters Islands. The Sisters are north of the Chathams in the middle of nowhere; the albatross colony provided a food source for the Moriori. But what a voyage to get there! In our fishing boat, it was three hours each way. I have no idea how long it would have taken in a wash-through raft. Six of us made the journey: Charles and Margaret, Kay Darby, our PA, Graham Smith on camera, Rod Wilson on sound, and myself.

About 10 minutes after leaving Waitangi, we struck high winds and five to six metre swells. At times the sky was completely obliterated by the sea. It was impossible to stay on deck — we had to huddle inside the wheelhouse with the skipper and mate, who fortified themselves on the journey with copious amounts of beer drunk from the bottle which, when drained, was chucked out the window into the ocean (there must be a river of brown ABC bottles on the ocean floor, leading to the Sisters). The smell of diesel was overpowering. After about an hour and a half I was feeling fraught that I'd put all our lives in danger. Should we turn back?

Graham was so seasick we had to take him outside, and prop him somewhere safe. At least he had fresh air. There were no life jackets on this boat. Others in our film crew were starting to turn various shades of green. Fortunately I’m a good sailor. To the boat crew this voyage and weather was nothing unusual — they’d done the trip many times. So, after consultation and agreement, I made the decision to carry on.

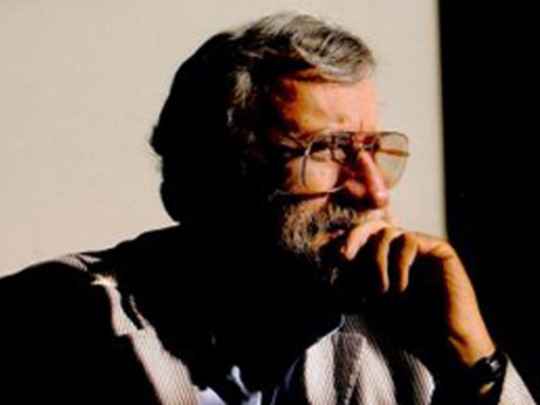

Director Wayne Tourell grabs a rare quiet moment on Rēkohu.

We arrived at the islands, and made it into the lee of the huge black sheer cliffs. Wow! It was utterly wild and beautiful. Above, albatross circled. How on earth had the Moriori landed on shore here in their wash-through rafts, let alone climbed these cliffs?. I was the only one capable of filming. Graham unsteadily checked the film and exposure for me, then I slung the CP16 on my shoulder and started shooting. The sky was grey white and very contrasty. The swell was rolling. There was no way I could get any closer shots with the long lens. I think I used every foot I shot in the finished documentary. I have absolutely no memory of our return journey.

The film crew: writer/producer Bill Saunders is front, centre.

Our final day of shooting was back on Chatham Island: a clifftop at a magnificent blowhole, sacred to the Moriori. They believed that upon dying, this was the place from which their spirits returned to their spiritual homeland. The day was blustery and stormy.

I’d asked Charles and Margaret to stand as close to the edge of the blowhole as was comfortable. As we lined up the shots, the spray from the blowhole got bigger and stronger. It appeared to be getting much too dangerous; they were getting blown around and drenched. I yelled to step back a bit, but they couldn’t hear me. Feeling slightly panicked, I ran over the slippery rocks towards them. Crack! My left leg buckled. I knew instantly that I’d broken a bone. Thankfully, I had on calf-high lace-up boots, which seemed to be holding me together. Not letting on (or admitting to being the last tapu victim) I just carried on. We got the scene shot and wrapped. Back at Waitangi Hospital, manned in those days by nursing nuns, an X-ray confirmed that I'd broken a bone in my ankle.

Filming the Moriori village constructed for the documentary.

Laid over these blowhole scenes were some of the last words spoken in the documentary.

Margaret: "At this moment I can’t identify strongly with the Māori as I used to — but then there’s nothing left of the Moriori culture to grasp on to."

Charles: "Our family and relations are the only living link with a people, a culture that’s virtually disappeared."

That was in 1979. In 1980 Moriori won Best Documentary at the local Feltex Television Awards. But it wasn’t until Bill Saunder's’s untimely death in 1995 that I began to learn there was indeed hope for Moriori. Maui Solomon, Charles and Margaret’s younger brother, had been a schoolboy when we filmed the Solomon family in Temuka. He became a leader in the Moriori renaissance.

At Bill’s funeral, I was asked by Te Iwi Moriori Trust Board to read their eulogy to Bill. It’s a beautiful tribute to the man, and to the documentary. Two quotes relay its essence.

"Since the screening of the documentary all those years ago, there have been other events which have marked the renaissance and revival of Moriori history and culture as a living reality. But it really started with filming of the Moriori documentary."

'Bill was instrumental in rekindling the flame of our almost forgotten heritage and bringing to light an important chapter in New Zealand’s history. Thanks to Bill, that chapter remains open and the text is being rewritten. This time the truth will be told."

Three weeks after his funeral, at the NZ Media Awards, Bill was awarded the Peace Prize for Moriori. A specially commissioned Moriori carving was proudly accepted on Bill's behalf by his wife, Catherine Saunders.

Twenty-six years later, in 2021, Moriori were finally recognised in a Treaty of Waitangi Settlement. Radio New Zealand reported that the settlement package included "a Crown apology, the transfer of culturally and spiritually significant lands to Moriori as cultural redress, financial redress of $18 million, and shared redress such as the vesting of 50 percent of Te Whanga Lagoon. Moriori chief negotiator Maui Solomon told Morning Report the settlement had taken 159 years."

I am so grateful and proud that in 1979, I was the director of a documentary that helped ignite the fuse that rekindled the flame of Moriori revival.

- Director Wayne Tourell has won awards for his documentaries (Moriori,Landmarks), TV series (passion project Hanlon), movies (Bonjour Timothy) and charity films (Missing).

More photos from the making of this documentary can be found here.