Mortimer's Patch - Day of Judgement (First Episode)

Television (Full Length Episode) – 1980

NZ's First Police Drama - A Long Shot Ratings Winner

Mortimer’s Patch was part of the local television renaissance, which began with the arrival of the two channel structure. With the surge in energy came fierce competition between Avalon and Auckland. The programmers — Des Monaghan on TV1, and Kevan Moore on TV2 — chanced reputation and budget to win market share. Successful productions, Close to Home and The Governor on TV1, and Hunter’s Gold, Gather your Dreams, Children of Fire Mountain on TV2 were the drama flag-bearers.

John McRae, back at TV2 from the BBC with an Emmy under his belt, argued that drama, being so expensive, had to be saleable internationally to be viable. He shrewdly picked the kidult genre, in period costume, as most likely to sell; period pieces wouldn’t date. But Mortimer’s Patch was to take TV drama in an uncharted direction. The prospect of it competing on an international market was slim, so it was a huge and expensive risk to increase TV2’s viewer numbers and loyalty, especially since neither I as producer, nor the first season's directors, had any experience in the genre.

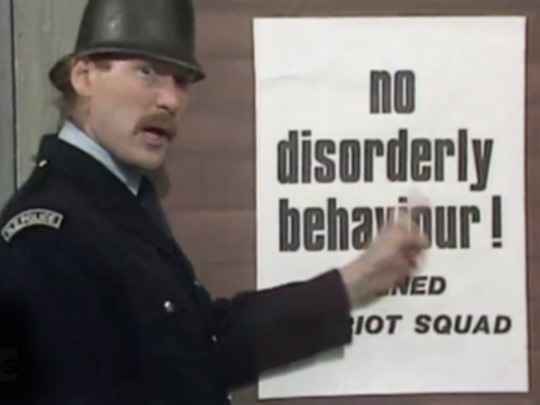

The local police series genre was by no means new to Australasia: Channel 7’s Homicide and Channel 9‘s Division 4 had been programme anchors for 14 and seven years respectively. In New Zealand, TV1 had the British Softly Softly, and TV2 had done well with Starsky and Hutch and Kojak: all hard acts to follow. My view was that we shouldn’t even try aping them. They were not a good fit for an essentially provincial and parochial New Zealand. A country setting would be much more familiar, and could be “your town”, thus eliminating any negative JAFA connotations.

A country setting also presented far fewer logistic issues for filming, such as noise, traffic and crowd control. Within an hour’s drive of Auckland was a wealth of settings: farms, vineyards, bush, beaches, fishing ports, wetlands, small towns, gravel roads, and countless villas and bungalows set in generous properties. I don’t recall any reference in the scripts to the geographic location of the eponymous patch — Cobham. The town was deliberately ‘Kiwi anytown’.

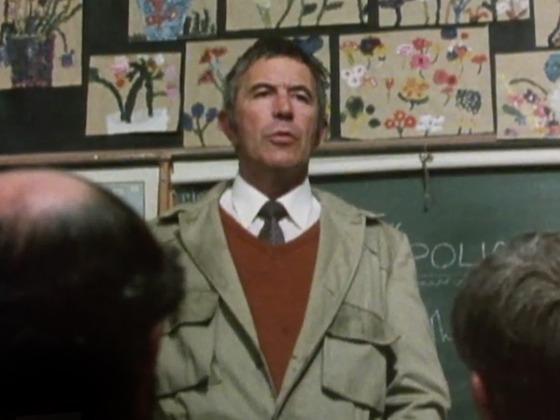

Script editor Christine McCourt was one of the only members of the team to have previously worked on a police show — she had started training in Australia on Division 4. The two of us built the format around the star qualities of Terence Cooper, who was about to come off Children of Fire Mountain. But Cooper’s persona was hardly that of a small town police sergeant, so we developed the character of Mortimer as someone who after a “spot of bother” in the city, had been sent to the town of Cobham to reflect on his future. This back-story begged an episode, but we never made it. However Keith Aberdein visited it in a great script, 'Friends and Relations', the last episode of series two.

Persuading Maurice Gee to write for us was a big plus, but not easy. Happily, he was attracted to the small town setting. His novels breathed provincial New Zealand, imbued with dark undercurrents, and voiced in pitch perfect idiom. Maurice freely said his love and vocation was the novel, and that television was a job which helped pay for his primary passion. But he also learned the magic of what actors do, what the camera does, and how much of his written dialogue could be replaced by their modalities [the various types of spoken communication, including interruptions, pauses, gestures, etc]. I got Maurice up from Nelson, to watch the cutting of a few scenes in an early episode. He soon grasped the alchemy that the director brews between the typewriter and the performances captured on film. Maurice started to trust what happened ‘downstream’ from his pages and came to both enjoy it, and write for it.

Terence Cooper was a highly intelligent, multi-talented and easily bored man. A bass baritone, a painter, a rugby player in Ireland, a fine cook and carpenter (he fitted out and opened his own Indian restaurant in Auckland). With his sharp mind and mischievous energy, he could be extremely trying and assertive for the much younger directors and assistant directors. Chris Bailey recalls that Cooper would use his large persona to try to push young directors as far as he could, to make them see it his way. But “if you stood up to him, he would respect you and then show enormous support”. Peter Sharp says that "you had to tell him to “f**k off” or he would swamp you".

Our police advisor, Assistant Commissioner Ross Dallow, told us that a key characteristic of an experienced cop was that “nothing could surprise him”. That was a tip that Cooper took to Mortimer: his close-ups, in suspect or witness interview scenes, were brilliant. His intense, intelligent eyes projected a sense of bemusement playing just below the surface.

Script editor McCourt suggested that Sergeant Storey should be Māori. Bastion Point had happened a year earlier, but the Springbok tour was two years away. TV drama, as we were developing it in 1978, was essentially Anglo-centric, and mono-cultural. Don Selwyn, as Sergeant Bob Storey, basically took on the mantle of making sure that his character would reflect a Māori ethos. He regularly asked for changes to dialogue to reflect that. Director Keith Hunter believed that, “Simply having Don as a major casting meant you had a strong, underlying Māori element”. We had no Māori script writers in our stable, and we didn't seek one. It wasn't until series three, under producer Logan Brewer, that two episodes were developed with distinct Māori storylines. Even then, they were not written by Māori, but by Dean Parker and Greg McGee. Director Chris Bailey's feeling is that it was Don Selwyn’s performance in Parker’s script about the 1981 tour which brought a visceral Māori sensibility.

Sean Duffy was working as a film editor when Keith Hunter backed him as Constable ‘Dimp’ Gilchrist. I think ‘Dimp’ was Cooper’s marvellous tag. Anyway, it stuck, and the axis of Mortimer and Dimp developed as pivotal.

Brian Walden, as production manager, had steered the logistics of all the kidult series and played a key role in developing a crew ethos. Although we had built up solid technical skills in Hunter’s Gold and others, fundamentally there was precious little experience in, or knowledge of the police genre.

Mortimer’s Patch was dropped after the first two series, caught up in the amalgamation of the Avalon and Auckland drama departments. The new head of drama, Ross Jennings, wanted a series which could be made faster and cheaper with a mix of film and video production, and with an urban edge to it. Both Sides of the Fence emerged. Whilst I accepted that Patch was expensive, it seemed a shame to drop it after just 14 episodes, when it was regularly topping the ratings. When you hit on the right chemistry — concept, writing, casting, directors, photography, sound, editing, music — it seems foolhardy to chuck it at the top of its game.

A year after Mortimer’s Patch was dropped, I explored the possibility of making an independent feature film based on it. The principal cast were up for it, and Maurice Gee developed a script. The BCNZ (ie the combined TV1 and TV2) agreed to license the concept and also to put up valuable services, including the NZSO, to perform Bernie Allen’s score. Peter Sharp directed and we were able to cast the brilliant Patrick McGoohan (Danger Man and The Prisoner) and young Brit Emma Piper as leads. As a cross-over genre film, Trespasses sat uncomfortably between TV and cinema and was not successful at the movies. It ran a couple of times on TV, and helped to keep the Mortimer ‘brand’ alive until it got a reprieve and a third series was made in 1983 (which screened in 1984).

All of us involved in Patch appreciated the confidence shown in us and the freedom given to us make our own judgements — luxuries rarely experienced today.

— After a decade working in news and current affairs, Tom Finlayson moved into producing TV drama, with Radio Waves, Under the Mountain and Mortimer's Patch. He did time as an independant producer then returned to TVNZ in 1993, to spend three years as head of production. Finlayson has also directed a number of documentaries.