Ngāti

Film (Excerpts) – 1987

A perspective

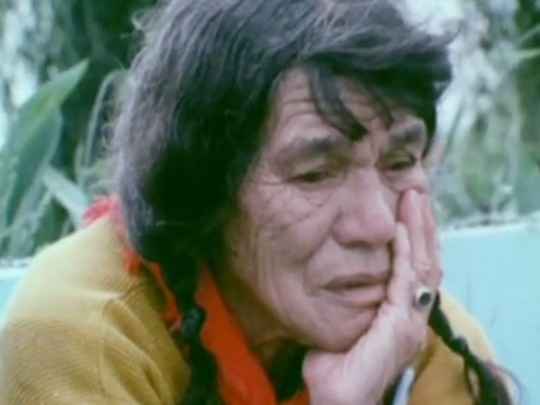

Toward the end of Ngāti, wahine toa Sally (played by Connie Pewhairangi) speaks about Māori autonomy; she calls for the community to reclaim ownership of its farms and fisheries. This polemic sums up the intention of director Barry Barclay (Ngāti Apa) and writer Tama Poata (Ngāti Porou): the need for Māori to take back ownership of their image and story. Ngāti holds an important place in New Zealand screen history as ithe first feature film to be written and directed by Māori.

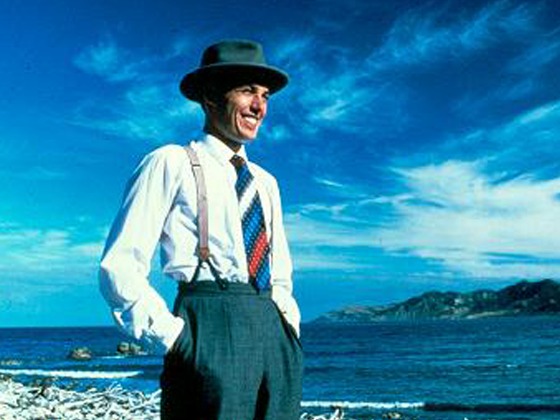

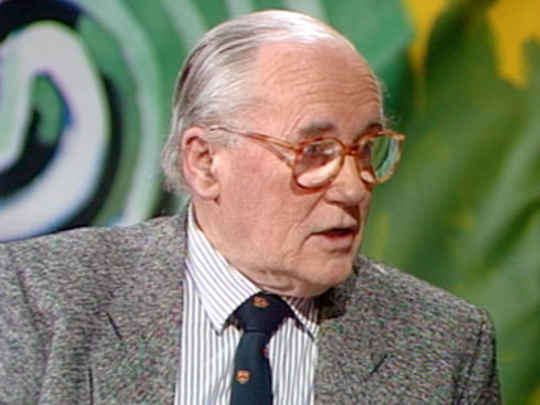

Ngāti was produced by NZ film industry icon John O'Shea, founder of legendary indie production company Pacific Films. O'Shea would go on to produce Te Rua, Barclay's second feature.

Screened as part of Critics Week at the Cannes Film Festival, Ngāti also won a best film award at Taormina Film Festival in Italy. French newspaper Le Monde called it "a victory"! Following its positive international reception and the discussions that came up regarding "the role of indigenous communicators working within a majority culture," Barclay wrote a book, Our Own Image. In it, he describes how he wanted to make a film that reflected the values of Māori culture, which involved a shift in attitude — or as John O'Shea put it, "from white to brown".

Barclay wasn't looking to a model, not Hollywood nor any New Zealand film that preceded it. Ngāti is a portrait of a community. As Barclay writes, "in a Māori community everybody counts." In an NZ Herald interview Barclay restated Poata's insistence that there should be no stars in the story: "It's the community, the whānau, that counts." This sense also infuses Ngāti's production. O'Shea describes "half crayfish for everyone" at lunch time.

Dalvanius, of Poi-E and Patea-cultural-revival fame, scored the film's music: unmistakably 80s bass and synth, with some traditional Māori waiata in the mix. The soundtrack was awarded top spot at the NZ Music Awards that year. Poata's script is filled with memorable lines. "Greetings to the ears being pissed in by that lot there," says Iwi (played in strong silence by Wi Kuki Kaa) of the bosses trying to close the freezing works. He goes on: "We hear the sound of our young people but we never hear the message."

Concerned with the lack of young Māori in the film industry, a wānanga was set up in Taradale in the year before the shoot. This initiative garnered wide support, with involvement from the Department of Labour, Hawkes Bay Community College, Pacific Films, Kodak and the National Film Unit. Graduates went on to crew Ngāti, forming a collective, Te Awa Marama. Ngāti was more than a good film — it was the beginning of a movement.

In a contemporary interview in Illusions, Barclay said:

"It's about being Māori - and that is political [...] political in the way it was made; a serious attempt to have Māori attitudes control the film. Political in having as many Māori as possible on it or being trained on it. Political in physically distributing the film or speaking about it and showing the film in our own way. Political in going in the face of a long tradition in the film industry here and abroad saying these simple things, without car chases or without a rape scene, actually have appeal, maybe it won't work ... I think a lot of the political struggle is to get through to Pākehā and Pākehā institutions that this is the way we think, therefore change your manners. This is the Māori world, take it or leave it ..."

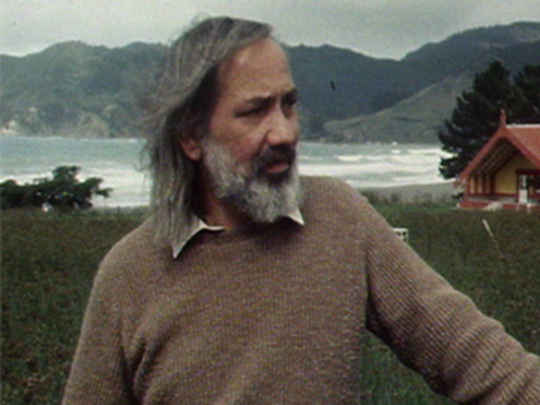

Before Ngāti, Barclay had worked extensively in television and film. This included Tangata Whenua, a series of television documentaries for which he collaborated with historian Michael King. The influence of Barclay's documentary past is evident in Ngāti's realist styling. Many extras and actors were East Coast locals.

Barclay details custom and daily life often using repetition and circuitous scenography: one by one the mourners wash off the tapu at a tap on a post as they leave the urupa; musterers move cattle along beaches and roads; at different points throughout the film characters stop on the road and call up to the sick Ropata.

Barclay said in a contemporary NZ Herald interview: "It was the biggest compliment to hear the Ngāti Porou elders say, ‘yes, that's us,' and to hear the young people say, ‘yep, that's us'."

Shot in Tologa Bay by Rory O'Shea, the landscape is dominant: dramatic cliffs rise to the top of the frame; tiny houses perch on the edge of the ocean. The atmosphere is thick with heat and dust. Critic Peter Calder commented in his 1987 NZ Herald review: "Its images are composed with a wistful and pensive restraint and its pace is easy and friendly. Yet bubbling beneath its surface is the most powerful political statement about Māoridom — and by extension all indigenous culture — our cinema has yet managed."

The international praise was reiterated locally. After being the only local feature chosen for the 1987 NZ International Film Festival, Ngāti went on to scoop the awards at the 1988 New Zealand Listener Film and Television Awards: winning Best Film, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Male Actor (for Wi Kuki Kaa).

The unique tone of Ngāti has not been repeated in New Zealand cinema. Though suffering from the odd didactic moment of dialogue, the film is defiantly lyrical, leaving a strong and lasting impression.

Sources include

Barry Barclay, Our Own Image (Auckland: Longman Paul, 1990)

Barry Barclay, 'The Control of One's Image' - Illusions no 8, June 1988, page 8

Barbara Rogers, 'Making movies 'for us' ' ( Barry Barclay interview) - The NZ Herald, 28 August 1987, Section 3, page 6