Off the Edge

Film (Excerpts) – 1977

Off the Edge - original 1977 production notes

"A beautiful and awesome film [...] Off the Edge is a stunner with one amazing vista following another [...] a thoroughly exhilarating experience and one that can be shared by the entire family." Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times.

The Story:

The story is a depiction of the longing in each of us to be free and to be part of the natural world around us. It is a fresh statement, a picture on a human scale, not the filming of an impossible dream. It confirms that fact that such experiences exist and are within our grasp.

The humour, the friendship and characters of these two comrades bonded together here amid the awesome power of nature, where they experience the contrasts of beauty and danger, solitude and exciting adventure, unfolds before us in a series of inspiring events.

The film provides a glimpse and an understanding of the joy in taking those calculated risks to experience a realm, a part of life most people have forgotten. We feel that everyone would like to be an explorer. It is an inheritance from the past and from childhood days when everything around us was new and exciting. The lure of adventure has been an irresistible force through the ages.

The production:

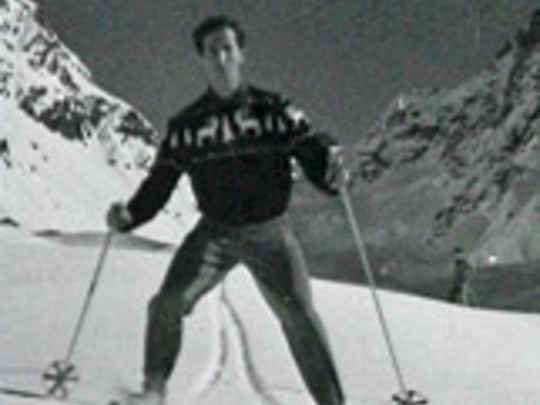

Every film has its own history of traumas and production and highlights, but in some respects we had more than our share. Because of the treacherous terrain and remote locations, we encountered nearly insurmountable filming difficulties, not to mention the recurrent risk to the life and limb of our cast and crew. Unpredictable weather conditions and the inherent hardships in filming on skis and hang-gliders at altitudes of over 1,000 feet, make our production story an exciting one to read.

Mike Firth, a New Zealander; Jeff Campbell, an American; and Blair Trenholme, a Canadian; all met while skiing in Val d'Isere, France, during the winter of 1970/71. Because of their English speaking origins and mutual love of skiing they all became close friends in a comparatively short time.

They returned to their respective countries and two years passed with no correspondence between them, then in 1973 Jeff and Blair received a telegram from Mike explaining an idea he had for a film, asking them if they could spend the New Zealand winter filming in the Southern Alps.

Jeff was heavily involved in hang gliding and brought two gilders with him. Mike and Blair were soon initiated and and it was then decided to incorporate hang gliding into the film. As Mike said, after seeing the first hang gliding footage: "We were wildly excited at seeing the potential of this new visual form."

The production covered a two-year span with nine months spent on location in the Southern Alps. In those nine months only 45 days were spent filming. The close proximity of the mountains to the Tasman Sea, only 20 miles away, caused frequent adverse weather conditions with winds sometimes in excess of 200 miles an hour. The fine weather, however, did much to compensate for their recurrent waits.

The crew flew up each day by ski-plane or helicopter to the head of the Tasman Glacier 15 miles away. Camera equipment was loaded into backpacks for mobility as the cameramen skied to the various locations. Geoff Cocks, second cameraman and sound recorder, had never skied nor been in the snow before. Nonetheless, some sequences required him to be dropped off in isolated snowy regions and perilous rock outcrops, thousands of feet above sea level.

On the first day's filming, our alpine guide, Gavin Wills, was testing out a slope for possible avalanche danger. Above him, a huge slab of ice cracked off under Mike's feet, starting an avalanche. Fortunately, Mike broke through to the base and did not fall into the rushing snow, but Gavin, standing further down the slope, was swept 1800 feet down the side of the mountain.

Fearing that Gavin was dead, the crew skied down quickly to find Gavin digging his way out of the debris which had spread out over an acre. Minutes later, while skiing further down this glacier, Mike fell into a crevasse. "I was poling my way across the glacier when suddenly the surface gave way beneath my skis. I spread my arms quickly to save myself, and found my feet dangling over a seemingly bottomless blue hole". To avoid similar situations, the crew roped themselves together to negotiate seracs and crevasses on their journey back to the waiting ski-plane.

Some sequences had to be filmed quickly due to the danger of the locations. The ice caves sequence was filmed in 20 minutes, wading through icy water under the overhanging cracking ice, setting up camera shots without any prior planning. Before filming, these caves had never been visited before, and to this day no one else has been in them. Giving the audience a Jules Verne voyage into the depths of the glacier that they would never otherwise see.

Because of our remote location, the film dailies were sometimes not returned from the labs for up to six weeks, and we had to go out and shoot blind, not knowing what our previous work had been like, or if our footage was any good. "Filming procedures were complex for the hang gliding sequences as there was no such thing as a second take. The kites would fly over a three mile distance through 5000 vertical feet.

The cameramen - there was usually two on the ground - would be strung along the flight path. A climber, with no previous experience in filming was trained as a cameraman to film in the more difficult locations. Mike Firth was filming the aerials from the helicopter which followed the kites, and as he put it, "Out there, whirling along the peak tops, thousands of feet above the glacier floor, the spectacular panoramic view made it difficult to keep my eye on the viewfinder while filming." He was not alone.

Jeff and Blair were finding it equally difficult. "Skiing in the mountains was one thing, flying in them, well it was something totally apart. We were no longer bound by the rules of the slope and found a new sense of freedom with this sport. It allowed us to venture places that have never been visited, except by our feathered friends."

Jeff commented, "I can remember the difficulties I had in executing my flight as planned. It seemed as though when my skis left the snow, my mind, in turn, left the carefully thought-out flights behind. All I knew was the beauty around me, the sensation of drifting so high above a landscape which had become so unreal. I had become part of it and that seemed enough. Finding camera positions and manoeuvering at predetermined points seemed so unnecessary. It wasn't until after we had landed that I found just how necessary it was. The filming, after all, was our purpose."

In walking, skiing, flying and filming amidst this strange land, we found ourselves closer to the forces at hand. We hope with Off the Edge you will re-experience and enjoy that thrill of discovery as much as we did.