Once Were Warriors

Film (Trailer, Excerpts, and Extras) – 1994

This title has three backgrounds:

A perspective

This is a brutal tale of an urban Māori whānau falling apart, as patriarch Jake abuses his rage and Beth struggles to hold the family together in a South Auckland slum. The film captured the attention of not only "shaken and silent" audiences worldwide, but confronted New Zealanders with life beyond the cliches of sheep and pretty scenery. The opening shot (South Island alpine scenery revealed to be a billboard above a grey industrial landscape) signals the film's intent. The New York Times called the result "social realism with a savage kick."

If one New Zealand film can claim to have effected social change and stirred debate, Once Were Warriors is it.

Before the Second World War 80% of Māori lived in rural areas. By the mid-1990s that statistic was reversed. The drift was driven by employment opportunities, but as Dr Pita Sharples says: "The change from the rural to an urban way of life was a huge culture shock. So many families were soon run down and the children were in trouble. They were broke, they had their power and water cut off, they owed rates and stuff like this. The discipline of the city was totally different from the discipline of the country. So there were huge problems."

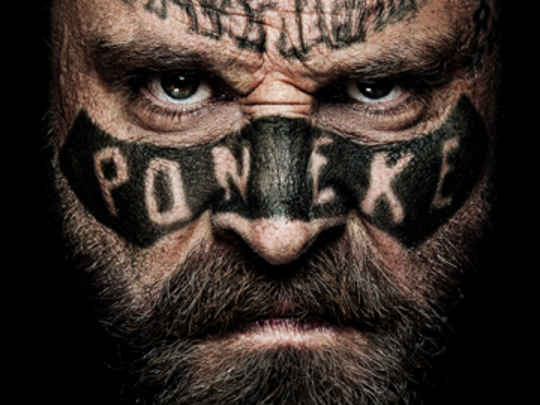

Gangs attracted some young Māori who lacked a sense of belonging and purpose. Many found themselves more connected to a rootless global subculture than their own history. This was the context in which Alan Duff's bestselling novel Once Were Warriors (his first) was published in 1990.

Production company Communicado was looking for a first feature to develop, and producer Robin Scholes secured the rights to the novel. Ian Mune was approached but felt the book was too difficult to adapt. The mantle was passed to Lee Tamahori, who agreed to direct immediately after reading Duff's draft. Although Tamahori hadn't directed any features, he had experience working as a crew member on several key NZ films and was one of the A-list commercials directors at the time.

Tamahori introduced Riwia Brown as a possible writer. Brown, Tamahori and Scholes thrashed out a basic outline for a new screenplay over a long weekend, and Brown was commissioned to write the new screenplay. They were determined to shape the novel's focus more to Beth's story and to make it more positive; the story about the clash of traditional and modern values became as much about the breakdown (and redemption) of family as reinvigoration of "warrior pride".

Brown says she saw it as a universal story, "but because this family is Māori there's another dimension to this story and that is, people finding their cultural identity ... [it] gave me a huge opportunity to make a Māori woman the heroine of this story and to write about what affects us as Māori, and that [includes] the good, the bad, and the ugly."

Tamahori's experience and contacts opened up the resources he needed for his feature directing debut. Advertising was booming, providing plenty of opportunities for Tamahori and his heads of department to put ideas into practice on big-budget commercials. The self-styled "classic hybrid" child of a European mother and Māori father, Tamahori had a privileged perspective from which to direct the story.

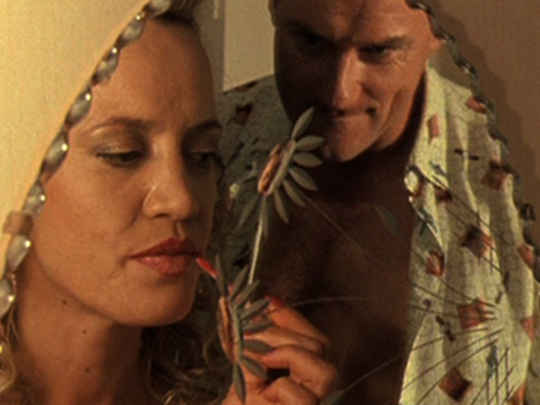

Once Were Warriors' unflinching depiction of domestic violence matched his professed keenness for films that evoke a response: films that "make you reel out of the theatre and you have to go to a bar and have a drink". Tamahori paired the film's social realist themes with a propulsive energy and style: quick-fire editing, rap music, and burnished black and red tinged visuals ("Māori colours"). Cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh evoked the badges and power symbols of the characters' world: work-out weights look like they come from a scrap metal yard and gang patches are lit with the same impact as corporate brands. Cast members were sent to the suntan clinic as part of the mission to have the cast "look as glamorous and as beautiful as the mafia did in The Godfather."

The powerful message struck a chord: that a family living in a hard and uncompromising new world wasteland might find hope in the strong traditions of their people and history. Pākehā and Māori audiences were stirred to acknowledge that this was one of "our" stories as much as Footrot Flats or Came a Hot Friday. Some men were provoked by the film to turn themselves in and seek treatment for violent behaviour.

It had nearly not gotten made: Scholes recalled in a 2010 ScreenTalk interview that the film only secured NZ Film Commission funding (after repeated turndowns) thanks to an impassioned speech by Gisborne police commander Rana Waitai. He stressed the project's timeliness in front of the Film Commission board. Scholes remembered distributors at the movie's premiere making bets on how little money it would make. The belief at the time was that "Māori stories would not succeed" commercially.

Warriors was such a success, some small town cinemas even reopened so that they could screen it. Until being knocked off its perch by The World's Fastest Indian in 2005, it was the highest grossing New Zealand-made film released in Aotearoa. It also scooped most of the film awards going at the 1995 NZ Film and Television Awards.

It was the first Māori story to find a sizeable international audience (taking $25 million at the international box office). Although some had heard of art exhibition Te Māori a decade earlier, for most overseas audiences Once Were Warriors was the first alternative image of NZ (to the cliches of scenery, sheep and All Blacks) they'd seen. The Lord of Rings trilogy and Whale Rider would later prove much more palatable advocates for New Zealand tourism.

Among numerous festival prizes Warriors took the Most Popular Film, Best Actress, Grand Prix des Amériques and Ecumenical Jury Prize at Montreal, and Best First Film at Venice. American critic Roger Ebert raved that Tamahori's "powerful and chilling" film was directed "with such narrative momentum that we are swept along in the enveloping tragedy of the family's life".

"Director, stars and writers all come from backgrounds that are at least part Māori, and together they create a powerful sense of longing [...]. None of these principals are familiar here, which makes the film's furiously energetic performances seem that much more intense." wrote Janet Maslin in the New York Times.

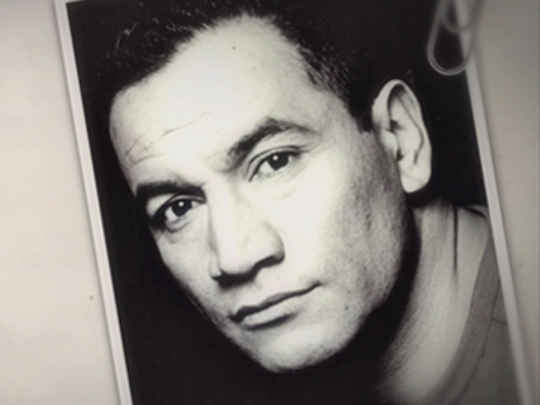

For actors Temuera Morrison and Rena Owen the roles of Jake and Beth represented career defining roles. Warriors launched the careers of Julian Arahanga, Taungaroa Emile and Calvin Tutaeo, and provided a Hollywood calling card for Morrison, Cliff Curtis and director Tamahori.

The casting of novices in the support roles was due to the tireless efforts of Don Selwyn. Selwyn toured the country auditioning kids from schools and men from gyms. He also coached Morrison nightly on set, demonstrating how Jake could be portrayed as a tragic, complex character.

The soundtrack effectively mixed pop gems pulled from the vault by Scholes (Poi E and What's the Time Mr Wolf?); commercial know-how in the hands of Murray Grindlay; and traditional instrument sounds, inspired by Hirini Melbourne's collection of taonga pūoro.

Dialogue from the film entered the culture. Jake Heke's order to Beth to "cook me some eggs" — with its mix of the mundane and a barely disguised subtext of threat — said much about New Zealand. The phrase was recognisable to real-life victims of abuse; at the same time it was mindlessly adopted by drunk scarfies who opening bottles of Speights with a fish slice in imitation of Jake the Mus. As with much of Once Were Warriors, it was an invocation to look in the mirror.