Pictorial Parade No. 195 - After Ninety Years

Short Film (Full Length) – 1967

On Denniston

Making this film was something I'd wanted to do since seeing the Denniston Incline in action as a 16-year-old boy. The experience of making it and then 25 years later its successor, remain two of my most treasured filmmaking memories.

When I approached National Film Unit manager Geoffrey Scott with the idea of making a Pictorial Parade about the Denniston Incline, his first response was “we don’t make films about things that are dying”. I persisted, telling him what a unique piece of engineering it was, how difficult life was for the people who lived at Denniston, and that shortly this would all disappear. He relented, and told me to go for it. This was one of the great things about working at the NFU in the 60s: we were frequently allowed to play with ideas we had.

The film’s cameraman, Brian Cross, was the key individual to insist we film the incline before it closed. The NZ Broadcasting Service, the infant Government TV broadcaster, had only a few 16mm shots of it, which were progressively getting shorter as they got nibbled away at for re-use. Cross was a senior cameraman, rail enthusiast and accomplished rail model-maker.

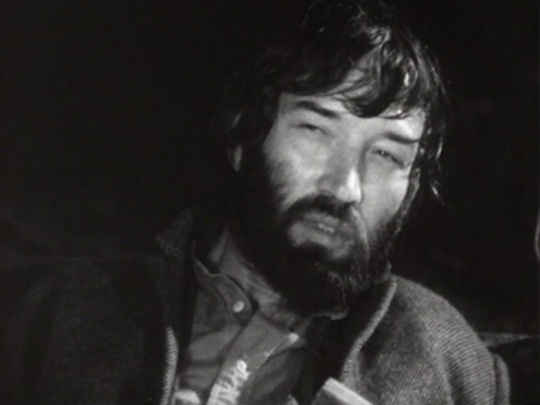

During our two weeks of filming in 1967, Cross, soundman Brian Shennan and I rode up and down the incline many times. Shennan and I stood on the back of the Q wagon, which as the incline pitched forward, was easy (although Shennan had heavy, bulky sound equipment to contend with). Brian Cross was sitting high on the loaded wagon, with the wooden legs of his tripod buried deep in the coal. Cameraman, camera and tripod were secured by ropes to the sides of the wagon.

The story of the cameraman on the Q wagon has taken a new twist on the Coast. A few years ago I heard one of the legends: that the cameraman was so scared he had to be tied down! So much for the courage of sitting on top of a shifting load of coal for a ride down which reached a nearly 45 degree angle.

Once we’d travelled down both sections of the incline, we had to get back up again. This time we were pitched backwards, maintaining our position by locking our arms hard over the rim of the wagon, and placing our feet behind short upraised bars on the footplate. It was exhilarating to be whisked uphill at thrilling speeds, lurching from side to side with branches literally whipping over our heads. As the upper incline reached its top and most steep section, we eventually were riding in a nearly horizontal backwards position.

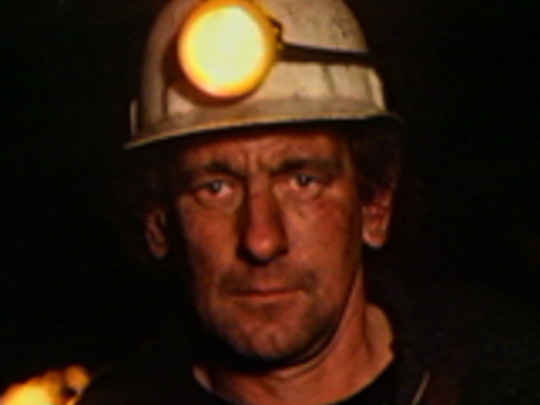

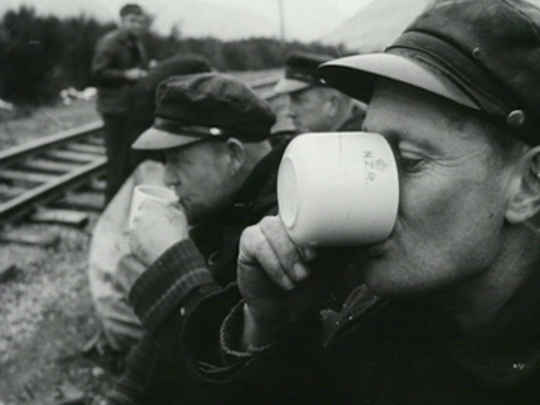

Our days of filming in the escarpment mine and on the operations of the incline and railway to Westport usually began around seven am. As mining ceased at three pm and the operation of the incline about an hour later, we would sometimes join the miners at the Red Dog Saloon — the last bar at Denniston, which was operating in an old shop as a relic of the Mount Rochfort Hotel, which had burned down a few years earlier.

Denniston was a sort of industrial version of a decaying wild west town, with its rusted tangles of abandoned machinery and almost total lack of vegetation. The general air of abandonment was further emphasised by the late afternoon fog creeping over the streets. Brian Cross would rhapsodise about the surreal ghost town scenes outside, and I would shout “let’s shoot it!”. But Brian had settled into the Red Dog’s hospitable atmosphere, and declared that he couldn’t operate a camera as he’d just had a beer. Strangely enough, this didn’t seem to affect his ability to drive back to Westport later, but it was the West Coast in 1967…

The third time this occurred, I announced that the following day we were not entering the pub until we’d captured all the romantic images of Denniston under fog that I wanted for the film — or the fog failed to arrive. To some, these rather desolate and dank images may be the essence of human isolation and deprivation. To us they were the atmosphere of pioneering legend and romance (later to be aided by one of most effective and satisfying scores on any of my films, by Max Winnie).

At the same time we were making After Ninety Years (a slight historical exaggeration, as the incline operated for 88 years) Brian Cross and my fellow NFU director David Sims were making KB Country, another Pictorial Parade about the last days of steam on the line linking Christchurch with the West Coast. Both shorts screened before feature films of the time (although some months apart). Both were very popular with cinema audiences. At the Embassy Theatre in Wellington, After Ninety Years was held over to screen with three successive feature films.

In the 1980s I left the NFU and with fellow ex-NFU colleagues David Sims and Kit Rollings, formed company Memory Lane Productions, using an overdraft to fund a film about the Rimutaka Incline. Our second film On Denniston utilised material from my original Denniston film, plus unused shots and sound tapes which colleague David Sims had saved in the 1980s, just as they were about to be thrown out before the Film Unit was sold to TVNZ.

On Denniston proved to be our best-selling video/DVD, with an estimated 15,000 VHS and DVD copies sold. And they still do.

- Hugh Macdonald spent over two decades making films for the Government's National Film Unit, including three-screen spectacular This is New Zealand and as co-producer of Oscar nominated short The Frog, the Dog and the Devil. Since leaving the NFU in the mid 80s, his work has included a number of films for rail aficionados.