Pictorial Parade No. 200 - Kb Country

Short Film (Full Length) – 1968

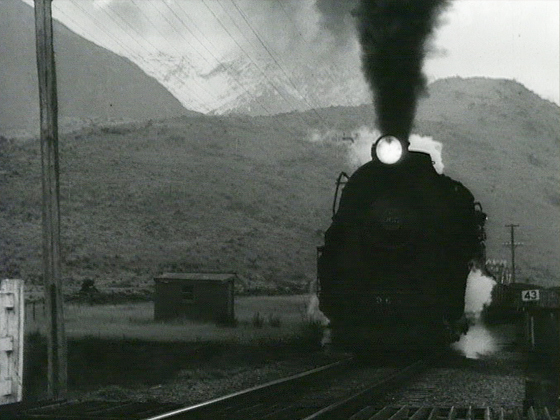

Racing a Locomotive Through Five Tunnels in Broken River Gorge

This excerpt on the making of Kb Country is taken from director David Sims' yet to be published memoir A Doodle in Prose - Jottings of a Premature Baby Boomer.

Back at Auckland Grammar School, I’d been a keen photographer of steam trains. After a few months working at the National Film Unit, I decided to come out of the closet about my interest. I had a railway project I hoped they’d let me make. But if they agreed — and it was a big if — we’d need to start soon.

I wrote up a proposal for a documentary on the massive Kb steam locomotives working the railway route from Springfield through the Southern Alps, up to Arthur’s Pass. I submitted it as a Pictorial Parade special to Ron Bowie, who was then the NFU’s Assistant Producer.

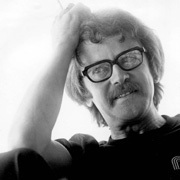

Ron was keen to assess the potential of new trainees, and an enthusiastic advocate for new ideas. Already colleague Hugh Macdonald, was away on the West Coast shooting the final days of the famous Denniston line. Macdonald’s cameraman was Brian Cross, who’d carved a formidable reputation risking life and limb to get the innovative shots for which the NFU had become famous. And Brian happened to share my passion for steam railways.

But could the National Film Unit be persuaded to make yet another film about dying technologies? The unit was known for touristy type films overcrowded with images of Milford Sound, plopping mudpools and mobs of sheep. Certain that this winter would be our last chance to shoot steam in action in the Southern Alps, I was careful to load my proposal with mouth-watering phrases like “magnificent scenic vistas”, “history in the making” and “tourist appeal”. This sort of stuff sat worthily within the Unit’s promotional brief.

The day before we left to shoot Kb Country, producer Oxley Hughan called me for a personal briefing. This was to be my very first location directing assignment; it was always a daunting moment for a junior to be summoned along the corridor to enter the office of the grand old man, in his sunset professional year. Hughan rose slowly to his full height behind his desk. Prominent forehead and eyes enlarged through the thick lenses of his horn-rimmed spectacles, shadowed by bushy hedgerow eyebrows above and a magnificent moustache — he looked like he’d been hacked from granite. When it came, his utterance bore a challenging message:

“Beware! Brian Cross is a maverick!”

*****

We flew in a turboprop Vickers Viscount to Christchurch, where we picked up a rental car, drove 40 miles west across the Canterbury Plains, and entered the dimly-lit hallway of the old Springfield Hotel, which would be our base of operations. I didn’t have to wait long to get firsthand experience of the legendary cameraman I’d been fortunate to inherit for the project. The next day we got down to business, traveling on a shunting service up to Arthur's Pass.

The night before I’d detected a certain reserve amongst the locals in the bar. This was quite natural in a country pub. We were ‘townies’ from up north and — even worse — a film crew. That was all to change. The locals hadn’t reckoned on the drinking and conversational skills acquired by the Gnome (as Brian was known) over a decade of filming around the country. Rounding out the crew, Vladimir (Val) Federoff was as skillful handling any type of drinking utensil thrust at him, as he was with a Mark Three Kudelski Nagra tape recorder.

Within a night or two they’d won over this vital patch of local territory. Although it was still the time of six o’clock closing, throughout the South Island friendly lights in public bars could be seen twinkling their hospitality across frosty paddocks, long into the night.

*****

It was appropriate we were shooting this movie depicting the last hurrah of steam, using technology that was “steam age” too. Our film stock and camera had direct family lines going back some 70 years before with the Lumière Brothers. Known in the industry as "coffee grinders”, our Arriflex 2Cs made so much noise that sound recordists kept well clear. Although effective sound was a comparatively recent innovation, location recording technology had only recently begun to make rapid strides. The iconic clapper board was very much alive, and still the best way to help synchronise sound with the picture. I was to spend much of my time on Kb Country haring around with the thing in no man’s land, between Val and the Gnome.

The Cass bank was the longest steep grade confronting the coal trains. If you stood in the middle of the tracks, you could look straight down at the locomotives as they struggled up the last few hundred yards to the summit. This location was just crying out for a telephoto lens.

I’d been in awe of the 16 inch telephoto lens from the first time I beheld its huge circular focusing wheel. The Gnome must have been aware of its audience appeal too; as he readied the massive 406mm lens to attach to the Arriflex on its tripod — now firmly planted astride the tracks — he stretched out the ritual of assembling its various components with all the aplomb of a medieval knight vesting himself of his personal suit of armour.

It was perfectly still up on the plateau as we waited to shoot Kb 970 hauling train 168 coming up the steep grade. For this shot I was operating in my capacity as safety assistant. As Brian would be crouched in the middle of the tracks behind the eyepiece of the 2C camera, it was important to establish an effective way of getting him clear in the moment of need. I’d stand directly behind him, and administer a good old-fashioned prod on the shoulder when things started to hot up. I’d then dive in and assist with evacuation procedures.

In due course Kb 970 presented itself, towing a full load of coal as it pounded around the corner into the home straight towards us. George the driver had been told to pretend we weren’t standing on the tracks in front of him, and the fireman had promised to turn on plenty of smoke.

The big Kb continued to get nearer. When I figured I had about 10 seconds before extricating him from the firing line, the Gnome suddenly sprang out from behind the Arriflex, grabbed his caboodle and dived off right of screen. Unfortunately one of the tripod legs caught the rim of the rail and propelled him into the ditch. As he went down the big lens dug into the embankment, bending the front plate of the camera. Then the Kb came slogging past. The Gnome emerged glorious and grimy from the ditch, a dazed smile etching his weathered features. Thankfully he was uninjured.

It was only when we watched the rushes back in Miramar that I understood why this maverick risk-taker had abandoned his usual policy of keeping on rolling while the universe was imploding all around him. Whereas I had the benefit of judging distances, observed through his telephoto lens, the Gnome’s world was highly focussed and blown up. Kb 970’s smokebox and number plate were full frame and advancing! When the movie was released, the shot caused gasps of horror amongst the audience at Wellington’s Embassy Theatre. And going by the way George the driver was nearly falling out of the cab, Brian Cross hadn’t been the only worried man that day.

*****

When we found ourselves down at the locomotive depot shooting big close-ups of driving wheels spinning around, it was thanks to one of the fitters from the Springfield Hotel. After hearing over a beer that these were difficult shots to film, he came up with the bright idea of greasing the tracks on the coal siding, attaching Kb 965 to sister 968 which was out of steam with the brakes full on, and then opening out the regulator. Nobody liked watching the torments this big engine now went through, struggling and heaving and going nowhere. But all agreed it was for a good cause. When we filmed the track gang relaying and ballasting the rails in falling snow up in the mountains at Staircase, the Gnome got in amongst their labours amidst flying stones and sleepers, hand-holding the Arri right in under their noses. But they took no notice. He was just another one of the drinkers from the bar.

*****

I peeked into the old social hall next to the Springfield Hotel where the lighting equipment had been stored. In the middle of the dance floor stood two 2K (2 kilowatt) lights and their heavy steel tripods. A big job lay ahead for these mammoths. We were going to shoot the crossing of two freight trains late at night, up at Cass Railway Station.

We nosed the Holden down the gravel road leading into Cass station yard. The weather forecast was good. About five thirty it started to rain. By six it had really set in. When the railways electrician from Otira had turned up around three to arrange a power supply for our two big 2K lights, the temperature was already plummeting. Tiny snowflakes began falling in the yard, fluttering around in stark relief against the brooding stand of pine trees surrounding us.

Kb 970 turned up on the first westbound service around seven o’clock. What with lugging all that lighting equipment in the dark we were tired, cold, and numb. With our temporary film crew of four, we had to light each shot as we went.

I knew that these trains were already affectionately hailed for their hospitality, willingly collecting deer stalkers at remote places along the line. But tonight the cargo was not mortal flesh. Since departing Springfield yard an hour or two earlier, a large pot of stew prepared by the cook at the Springfield Hotel had been bubbling its way up through the Staircase and Broken River Gorges on the guard’s pot belly stove. We sat in our humble shelter by the tracks at Cass partaking of its reinvigorating properties, washed down by whisky from our enamel jugs.

With a 2K now mounted up on the water vat for our two train crossing scheduled for around midnight, we settled in with our whisky for the long wait. We should have counted ourselves privileged to have this Railways sparkie with us for the night. To come and help us out, this chap had thought nothing of chugging the first part of his journey up through the freezing five-mile Otira Tunnel on his open air motor trolley — the very same place Margaret Thomson had two decades earlier shot those pioneer night scenes for her film The Railway Worker.

When we first heard 970’s whistle coming back from the pass, we were taken by surprise. It sounded so near; yet the train was still a good five miles down the valley. The acoustics up here in the mountains could be deceptive. About the same time, out of the opposite direction 965 came clanking to a halt on the siding with the next westbound freight train. That was the thing about these country stations. After hours of nothing, suddenly it was all on.

It was now time for us to add our very own magic to the occasion. As 970 approached, the Gnome flicked the switch and Cass yard became an instant pool of light in the middle of blackness — a temporary film set with our lights defining a fairyland of snow flakes, a man with a movie camera, and a steam engine bursting through the frame with snow-covered coal wagons trailing along under a long wraith of pure white steam. As quickly as it had come about, the surreal vision was gone.

It was suddenly a cold wet night with two hours of derigging our equipment in the slushy darkness before we got back home about four am. Luckily we’d got away with lighting Cass yard, without anyone being electrocuted by the naked electric wiring in the freezing wet conditions.

*****

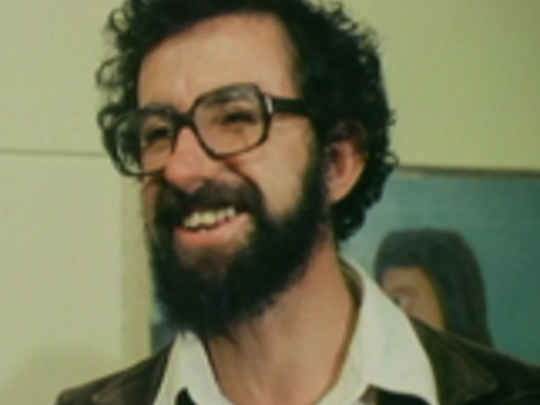

Ray lived at Kowhai Bush in one of those cute railway houses built as kitsets in Frankton, and shipped to the far corners of the Railways empire. From what I could see, Ray’s was the only house in Kowhai Bush. The tiny lean-to shelter out by the railway tracks housed his four wheel motor jigger. As the local ganger, he relied on it as the sole means of patrolling this lonely section of the Midland line, westbound up through Pattersons Creek, Staircase and the Broken River Gorge.

Ray was a lightly-built young man with a weather-beaten face. He didn’t mean to lean forward and peer past you when you were talking to him. It was just that he’d got so used to looking ahead around corners, what with all the tunnels and sharp curves on his patch. In a sense he’d evolved an ergonomic harmony with his jigger — a sort of human extension of the machine if you like. Ray was quick to point out that it wasn’t just a jigger. It was a velocipede, which was the correct Railways term for it. And it wasn’t just a velocipede. It was a sporting type of velocipede — one without any roof or encasing shelter — specially designed in case Ray needed to instantly vacate the premises if a train suddenly came roaring around the corner.

Ray was an approachable drinker at the Springfield Hotel, and we quickly struck up a fruitful alliance. Getting into Staircase and the Broken River Gorge with our camera gear would have been difficult unless you went by trolley, so by prior arrangement Ray would drop us off while patrolling his patch, and pick us up on his way back.

Recognising something in the spry little fellow, we quickly improvised a sequence with Ray and his velocipede, in the style of comedian Buster Keaton. It went so well, we decided to mention that bigger things lay in store for Ray and his machine. His stint as Keaton was only a shakedown for the big show. Over a few drinks one night we got to talking with him about how good it would be to get some “different sorts of shots” of a Kb on the way up to Slovens Creek Viaduct. Not the usual boring sort of stuff — no, this was something which only he could help us pull off.

“What if we tracked ahead of a Kb on a heavy freight train looking back as it pounded up through the tunnels along the cliff of the canyon overlooking the Broken River? And using him and his trolley as our camera vehicle?”

The following morning, with Val traveling back in the guards van, Brian and I presented ourselves with our official engine passes from Head Office to George (a different George), the driver of our train who after a cursory glance beckoned us to climb aboard. We were on our way towards our rendezvous point with Ray up in the mountains. As he brought the the Kb to a standstill across the Broken River viaduct, about 50 yards short of tunnel no 12 , George was to come out with some pretty powerful utterances.

The man had terse comments to make about the safety aspects of the proposed manoeuvres, which had been sprung at him out of the blue an hour or so before by the guard, who’d just got it in a telephone call from Ray. He wound his diatribe up along the lines that the strategic planning of train movements was not a practice usually conducted from a hotel bar — especially by people who were “one over the eight”.

Then he climbed down off the engine and strode over to Ray, who all this time was trying to have a quiet smoke on his trolley out of harm’s way. I only got to overhear snippets of what followed but in a nutshell he seemed to be trying to point out that this was a busy line and as our locomotive was due up in Arthur's Pass on a tight turnaround schedule to bring back an eastbound coal train, speed was of the essence. He rounded things up by saying “now let’s get this bloody circus over and done with!”

The driver likely understood only too well the calamity if things came unstuck. Beyond our small group, there was not another living soul with an inkling about what was being hatched at the entrance of tunnel 12. If there was an accident there’d be no rescue party hovering in the wings to whisk us out of such a remote spot. Ray’s jigger was now hastily positioned back on the rails in front of 970, and wheeled back and forth so that the Gnome (who was expertly roping the Arri 2C and tripod to the velocipede) could determine an acceptable distance looking back at the train.

After what must have been the shortest council of war ever held — it boiled down to the crucial issues of coordinating two moving objects, namely a flimsy jigger being hotly pursued by the heaviest item of transport ordinance which the nation could throw at it — we all set sail.

We must have presented a strange sight as we entered tunnel 12. Out in front, scuttling along the tracks like an ant ahead of the train, our tiny conveyance was completely obscured by a veritable pyramid of humanity. Somewhere in the middle, the Gnome straggled the centreboard, arms and legs enveloping the camera. Behind him, his microphone blindly pointing back over the Gnome’s head, Val crouched, head down enveloped with head phones monitoring his meters. Plus me also facing rearwards, half standing and half kneeling on numb knees, a protective hand clutching each of the crew’s shoulders. And last but not least, the only man on our conveyance who was actually looking in the direction we were going — Ray at the controls.

We hadn’t been under way for long before some serious flaws in the battle plan manifested themselves. For a start we were wasting all efforts deploying any kind of communication with the driver, even the most rudimentary of semaphore signals. Quite simply, none of us had any spare arms and legs to wave around. Anyway that was all academic. For all those great shots we’d come to get, we needed to be fairly close to the locomotive’s smokebox, meaning we’d be out of the driver’s line of vision. Also, the mile or so we’d chosen of this most spectacular section overlooking the Broken River Gorge happened to sport no fewer than five tunnels, some as long as a quarter of a mile. So we’d be hidden in the darkness a lot of the time anyway.

In any trolley man’s life the natural instinct is to avoid being in a tunnel when there's a train in the offing. By and large, unless one had suicidal tendencies it was unthinkable to go out of your way to be in a tunnel with a train, unless you were actually traveling on board the thing. Very soon after we plunged into the next tunnel — ominously numbered 13 — it became clear that Kb 970 was catching up with us.

I’m advised that in moments when one is confronted by a threat to life and limb, the hapless soul turns to salvation from the most immediate quarter. In this instance the driver of train Kb 970 could be quickly ruled out. He'd made it very clear that he’d be powerless to do much if our plans came unstuck. That being so, Ray was our only man. After all, had he not endorsed the whole scheme as a neat idea in the bar the night before? Surely it was just a matter of opening the throttle wide, and he'd have us out of this mess in a jiffy? Sadly, no. Within that supposition lay the second gaping hole in the battle plan.

It seems that what with the Kb gradually getting up to its operating speed, Ray would need to shift up a gear to stay at a safe operating speed for all our sakes. With the wisdom of hindsight, he wished he’d made that all-important gear change outside in the open where he could hear his engine revs before we plunged into tunnel 13, instead of being confronted with the problem when we were inside it.

On his usual beat, tootling along on a fine day with just the birds in the heavens and a river cascading below in the gorge, changing gear would be a doddle. But the cacophony of Kb 970 resounding inside the tunnel made for a hell where it was impossible for Ray to hear the pitch in his motor, so he could effect a successful gear change. Put simply, if he failed and it stalled, the Kb would be upon us in seconds and we’d all be mincemeat.

With the fiery monster bearing down upon us, Ray had but one option and that was to run his motor well up beyond the range of revs permitted in the instruction book — going faster than it had ever turned over in its life — in the hope we’d reach broad daylight before the inevitable happened. We thanked our lucky stars as we burst free into daylight, just seconds before a huge cloud of steam came billowing out of the hellhole tunnel, pushed by the bulk of the steamer’s massive ramrod boiler. Then the behemoth itself made its appearance, popping menacingly out through its self-inflicted shroud.

At this moment it’s opportune to turn our attention for a fleeting few seconds to the Gnome — lest we forget this blessed man — crouched down, right eye inside the viewfinder of his trusty Arriflex, blazing away selective bursts of our precious black and white negative film to the bitter end. A Gnome impervious to the dangers all around him.

In the few seconds before the monster came at us out of the tunnel, Ray had been making the most of the comparative silence to gauge the pitch of his motor and rearrange the cogs in his gearbox. With the crucial gear change now in the bag we took off. It had been a close thing. For the remaining three tunnels up to our planned halt at the end of the Slovens Creek viaduct, we puttered along the tracks at a safe distance, where the worried train driver could keep an eye on us.

Suddenly it was another normal morning again. Away in the mountains, a kea screeched. Below us in the ravine, Slovens Creek gurgled its way into Broken River, just as it had been doing for thousands of years. At the appointed place by the viaduct Ray had the jigger off the tracks as the big steamer lumbered up to a stop beside us, simmering agreeably away, just a tame pant now and again from its two big brake pumps, and the odd gush of hot water onto the tracks. Nobody would believe that just moments before this leviathan had been trying to run us down.

Soon the train was gone. The peace and calm were uncanny. The Gnome, who’d stuck to his post throughout the drama like a musician on board the Titanic, had conjured a cigarette from its packet and was reclining lackadaisically against the motor trolley. Smoke wafted lazily out of his nostrils into the still air.

Val was the same. Easing the headphones from his ears, he reached for a tailor-made Matinee out of a cream packet, while the lines on his face rearranged things until he was smiling like a lizard which had been sunning itself on a rock all morning. You never knew with Val. After all those years in a Japanese concentration camp during the war, any other ordeal would pale in significance. Both these old pros had got through some pretty sticky situations in their time; I was sure they wouldn’t flinch, even if you dropped a bomb next to either of them.

But I had another theory. Having heard about the dangerous antics cameramen like the Gnome had been getting up to over the years, I think I knew why he was so fearless during our charge into the valley of death. Face buried in the viewfinder, the Gnome had passed through the portals into another world...Movieland.

All the time I’d been terrified for our lives, he wasn’t with us at all. The boy in the man had triumphed, and the Gnome had become another one of those kids jumping up and down in a suburban flea pit, on a Saturday afternoon. And up there on the silver screen, causing all the excitement, a big steam train was bursting out of a row of tunnels. In this hallowed temple devoted to the filmmaker’s art, there was little risk to life and limb. And certainly no show of getting killed by a steam train.

Perhaps the Gnome could sense what was passing through my mind. While we got the gear stowed onto Ray’s trolley, he turned to me and with one of those succinct verbal outbursts so popular with locals in these parts, summed up the morning’s activities:

“Christ, that’s going to look bloody good on the big screen!”

- David Sims worked for government filmmaking organisation the National Film Unit for over 20 years. The longtime train enthusiast was able to make further train films as part of company Memory Line Productions, and as director of The Truth About Tangiwai.