Te Matakite o Aotearoa - The Māori Land March

Television (Full Length) – 1975

The Making of Te Matakite o Aotearoa

The 1970s were exciting and changing times. We had recovered from the 60s, and we baby boomers were flexing our muscles both culturally and politically. As the song said, “...the times they are a-changin'…”

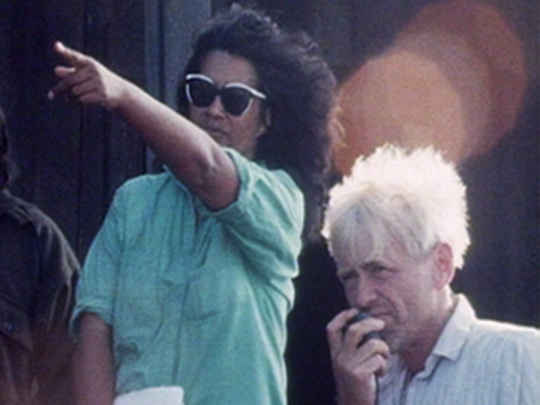

I was a young filmmaker, heading up a filmmakers' co-operative: Alternative Cinema.

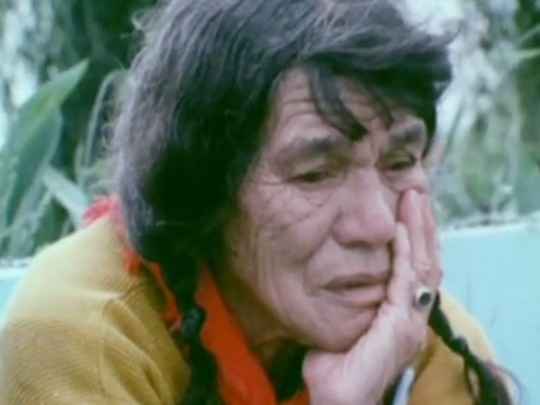

Being around the edge of the political scene that was active in Auckland at that time, I learned of plans by a group of Northern Māori to undertake a protest march from Te Hapua in the far north to Poneke (Wellington), to protest the alienation of Māori land. It was to be led by a matriarch and female leader of Ngāpuhi, Dame Whina Cooper.

This seemed to me an ideal opportunity to have a shot at making an observational type documentary, and at the same time help spread the message of the march to a wide audience.

I met with Whina and some of the march organisers, and explained my aims and filmmaking philosophy. It was basically to capture what happens when it happens, and attempt to portray the spirit and atmosphere of the undertaking as well as explain its underlying reasons and message. Eventually, I was given permission for my crew (as yet to be found) and I to travel with the marchers, as part of the core group. There were to be no other film people allowed to travel the whole distance, or to be given such close and intimate access.

The next challenge was to raise the money to make the film, as it was to be well beyond the hand to mouth productions I'd previously been involved in. I approached the newly established TV2 network; being set up in some old side streets in Auckland, the channel was in charge of its own programming. Eventually they agreed to help support the film, in return for New Zealand screening rights. It was to be the first ever NZ documentary to be shown on TV2.

The arrangement with TV2 was that they would supply the camera equipment and film and processing, but more importantly they would allow a good friend of mine and great cameraman, Leon Narbey to travel with us the whole march and be the main cinematographer. Leon was then a staff cameraman at TV2's Christchurch offices.

Phil Dadson was another friend and member of the Auckland co-op. We had worked on short films together; he became the documentary's sound recorder. The final member of our small team was an Australian filmmaker who was renting a basement room in the co-op's building, and surviving by making candles there to sell at the local hippie market. Gil Scrine had travelled on the protest boat Fri to Mururoa, when it sailed to confront the French over the Pacific H Bomb tests. He was to be the camera assistant and general hand on the road.

With the crew in place, we still had to fund the daily shooting expenses and the numerous post-production charges which making a documentary that was contracted to be delivered for screening in prime time entailed. I didn’t want to be associated with an unfinished programme.

Using contacts in some of the numerous political groups that were active at the time, I managed to scrape together enough funding to cover the basic budget we had. Anti-racism church groups, the Polynesian Panther Party and Ngā Tamatoa all helped get the film off the ground.

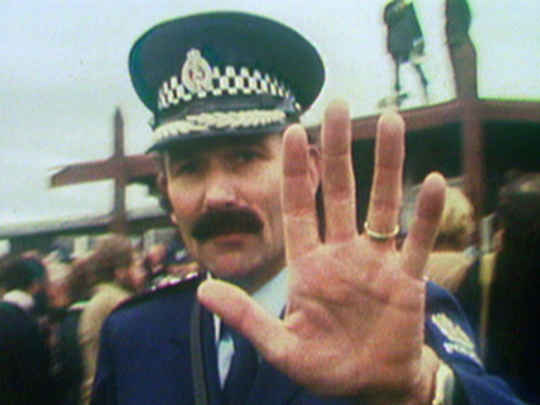

The great fear of making a documentary on an open-ended event such as a march that was planned to take at least a month to complete was we didn’t know what we would have to film, and what was going to be important. We had limited film stock, and lacked the freedom of today’s “when in doubt, shoot it” digital environment.

Also there was the background fear of what we'd get to film, and whether we'd get footage that made a good documentary, suitable for a TV audience. We didn’t know what might happen when we hit the road. Would anyone come? Would the march reach its destination as sore feet and the endless miles took their toll? I didn’t intend to use any narration to tell the audience what they were seeing, wanting to rely on what actually happened in front of the camera. It is a risky style for covering an open ended event (its interesting to note in hindsight that the completed hour-long film was made on a ratio of just 4:1 [the ratio of footage shot over how much ends up being used in the final cut] — ie we only shot just over four hours of total film time on an event that took so many weeks to unfold!)

After buying a secondhand Holden station wagon to use as a crew car and packing our few bags of gear, the four of us turned up in Te Hapua to start on our long journey south. We were to spend the next month eating and sleeping on marae down the length of the North Island, spending time with some remarkable and dedicated people; sharing their passion, humour and the kaupapa of the march. It was a remarkable journey, both personally and professionally and it would eventually lead to a finished documentary, Te Matakite O Aotearoa.

The story of a group of people with dedication, determination and dignity took their message to the country; a group of people who marched into history.

- Geoff Steven founded filmmaker's co-operative Alternative Cinema in 1972. He went on to direct documentaries on China, tattooing and Centrepoint, plus features Skin Deep and Strata. After time as a programme commissioner at TV3 and TVNZ, Steven now leads Our Place - World Heritage, a photographic databank of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.