The Piano

Film (Trailer and Excerpts) – 1993

A Perspective

They are instantly recognisable images: a grand piano sitting on a wild New Zealand beach; a pale-skinned and windswept mother and daughter in black bonnets; a piano tumbling off a waka and descending into the Pacific, its owner tethered to it. And who can forget the finger chopping; the corseted yet graceful collapse of Holly Hunter's Ada into the copious mud of 19th century New Zealand?

The opening shot of The Piano establishes a strong point of view, with Ada looking through her fingers in a child-like game. Her internal voice narrates: "I have not spoken since I was six years old. Nobody knows why, least of all myself." The fiercely strong-willed protagonist's father is sending her across the world, from Scotland to an unknown New Zealand. There she is to marry Stewart (Sam Neill), a man she has never met.

Critic Roger Ebert describes The Piano as "one of those rare movies that is not just about a story, or some characters, but about a whole universe of feeling." Vincent Canby's New York Times' review echoed Ebert: "Ms. Campion somehow suggests states of mind you've never before recognized on the screen." On website Rotten Tomatoes, The Piano scored 100% in its summary of top critics' reviews.

The Piano's combination of sexual awakening, music (the renowned score, by Michael Nyman, figures as Ada's surrogate voice), and an isolated colonial New Zealand bush setting proved a killer combination. And not just with the critics; Jane Campion became the first female director, and only New Zealander (to date) to clinch Cannes' prestigious Palme d'Or award (shared with Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine).

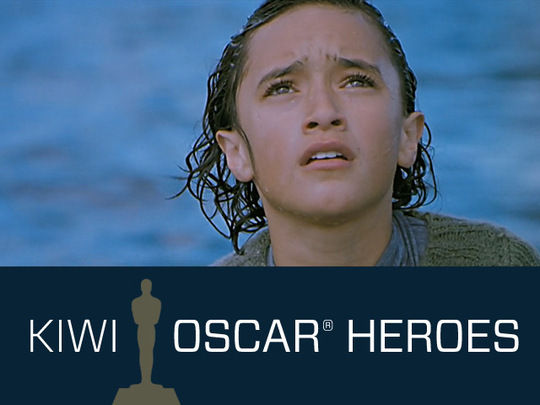

Campion was also awarded Best Original Screenplay at the Oscars, and Hunter's performance as Ada won for Best Actress. The most memorable Oscar The Piano collected went to Anna Paquin, who was awarded Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Flora, Ada's equally wilful and spirited daughter; 11-years-old and fresh from Lower Hutt, Paquin was beamed out to millions, sweetly gasping as she accepted the award.

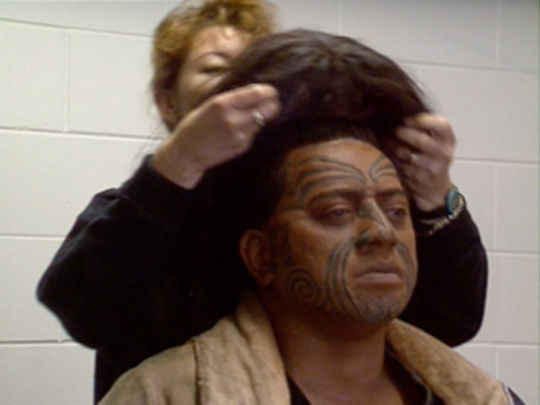

Cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh, who had collaborated with Campion on An Angel at My Table, was also nominated for an Oscar for his Piano work. Other staples of the Kiwi screen industry involved in the film included Alun Bollinger (renowned as a cinematographer in his own right) operating the camera, a young Cliff Curtis in a minor role, and the casting agent with the magic touch, Diana Rowan (who also discovered Keisha Castle-Hughes for Whale Rider).

The Piano grossed US $34 million in its first five months of international release. In his book Selling New Zealand Movies, Lindsay Shelton describes how this was "ten times as much as any earlier New Zealand feature had earned in the United States." The film was especially successful in Europe, and in France it broke records for a foreign release. The Piano was an art film that was also internationally commercial; an achievement that is almost exceptional in local film (arguably Once Were Warriors straddles the same divide).

Indeed The Piano was acquired by American production and distribution company Miramax and, along with Pulp Fiction (1994), was key in establishing that company's reputation for being able to mix box office success with indie distinction. Locally The Piano's success added to ongoing 'culture wars' debates about the sorts of movies that New Zealand's small industry 'ought' to be producing. Prescriptions were broadly divided into two camps: 'idyosyncratic arthouse', and 'mainstream genre', with The Piano defiantly pegging its tent in the former.

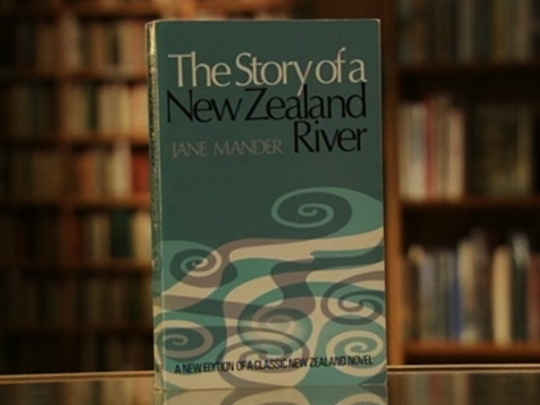

With success comes controversy. Some people found the similarities between The Piano and Jane Mander's novel Story of a New Zealand River (1920) too close for comfort. Others, such as Leonie Pihama, were critical of the way Māori were represented in the film's final cut, with their presence — as maids and man-servants or the source of an exotic ta moko for Keitel's Baines — described as being little more than ‘blackground'.

Financed by French construction magnate Francis Bouygues' CiBy 2000, and produced by Australian Jan Chapman (Campion was also living in Australia by this point), the customary trans-Tasman Phar Lap-ian battle also ensued. New Zealand arguably came out on top, with Campion commenting in an interview with The Herald, "[i]t's a film made in New Zealand by New Zealanders and it's very obviously a New Zealand film."

Certainly The Piano captured a palpable sense of Pākehā experience in 19th Century New Zealand. The landscape on which Ada's melodrama plays out is one with which the settlers are unfamiliar. They are aliens in the rain-soaked bush, amongst giant looming trees; Sam Neill's Stewart struggles to discipline it with his axe and English manners.

The details evoke what Campion called the "subconscious" of the land: strange bird sounds (kōkako, ruru, kiwi) peal through the forest persistently, underscoring the piano. It is a place in which Ada wrestles for identity.

Production designer Andrew McAlpine recalls: "we often altered the landscape to heighten the feeling of a particular scene, as in the scene where Stewart attacks Ada [see third clip], where the setting was too open so we gave it a web of supplejack, an anarchical tough black-branched creeper which we devised into a web, a huge net, like a tentacled nightmare in which Ada and Stewart struggle."

The Piano raised New Zealand's profile abroad. People were intrigued by the representation of New Zealand as a primeval brooding landscape — "at one point we are staring at a vast, virgin beach, as it might have looked at the beginning of time" (Vincent Canby in The New York Times). That attention was satirised in Topless Women Talk About Their Lives when a lost German tourist looking for the black sand west coast beach on which Flora pirouettes, becomes a key part of the film's plot.

Following its success, Paquin, Campion, Dryburgh and others have forged highly successful international careers. Back home The Piano is etched in our cinematic consciousness.

- Catherine Bisley is a Wellington-based director, writer and photographer.

Sources include

Peter Calder, 'Playing from the Heart' (Interview with Jane Campion) - The NZ Herald, 16 September 1993, Section 3, page 1

Jane Campion, The Piano (Andrew McAlpine quote) (New York: Hyperion, 1993)

Vincent Canby, 'The Piano (1993)' (Review) - The New York Times, 16 October 1993

Roger Ebert, 'The Piano' (Review) - The Chicago Sun-Times, 19 November 1993

Lindsay Shelton, The Selling of New Zealand Movies (Wellington: Awa Press, 2005)