Part one of six from this documentary (for viewers within New Zealand).

Part two of six from this documentary (for viewers within New Zealand).

Part three of six from this documentary (for viewers within New Zealand).

Part four of six from this documentary (for viewers within New Zealand).

Part five of six from this documentary (for viewers within New Zealand).

Part six of six from this documentary (for viewers within New Zealand).

Three New Zealanders: Janet Frame

Television (Excerpts) – 1975

A perspective on Three New Zealanders: Janet Frame

Three New Zealanders: Janet Frame is Endeavour Television's first documentary in the series of three made to mark United Nation's International Women's Year in 1975 - the other two are about Dame Ngaio Marsh and Sylvia Ashton-Warner.

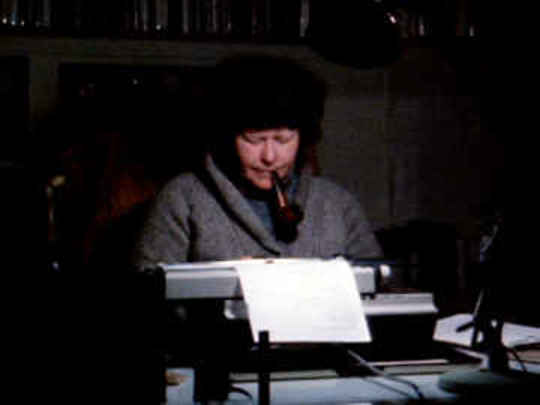

"Some authors are articulate and some aren't. We need to acknowledge those that aren't", Janet Frame says at the beginning of this film. The interview that is central to this piece negates any stereotypes about Frame's inarticulacy or shyness. The extensive rare footage of this internationally acclaimed and much loved New Zealand writer presents a confident writer in her prime.

The interview by Michael Noonan was conducted at Whangaparoa Peninsula where Frame (aged 50) was living at the time, in a fibrolite bach on a hill surrounded by the sea and tides, and amongst fruit trees, manuka hedges, vegetables, Kauri gum and pipis and the "useful material" for her writing that her neighbours presented. She'd moved there in 1972 for its relative seclusion from the "penis-motormowers being worked in the weekend" of suburban Dunedin.

Frame's most recent novel was Daughter Buffalo (1972). She was awarded the Winn-Manson Menton Fellowship to France in 1974 (later renamed the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Fellowship). When the interview took place in February 1975 she was struggling to find a writing groove amidst an invasion of summertime holiday-makers, and the encroaching construction noise of a new subdivision.

She told her friend, American painter Bill Brown, in a letter that she had spent, "eight solid hours being filmed and today I'm sunburnt on my face and my eyes and my lips and there's the usual reaction after such experiences ... I appeared as what I am, a complete ninny with not a word in my head."

But despite Frame's apprehension, on screen she is confident and self-assured, with no hint of the well-known tragedies (poverty, death and mental illness) that marred her early life. She discusses the sources for her stories, energizing experiences in America (several periods spent in East Coast writers' colonies), herself as a young writer (winning a year's subscription to Oamaru Athenaeum), and her family (her Mother's love of poetry), amongst other things. There are shots of her and Noonan clearly at ease in each other's company, drifting along a Northland beach in high summer.

Some of Noonan's questions reflect nationalistic concerns of the time. "Have you ever considered the supposition that you are one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century?" he gushes. Frame looks distinctly uncomfortable. She replies, "That question doesn't reach me. No it doesn't reach me. It's out of my province." (No doubt we were still marvelling that New Zealand had managed to produce such a talent).

Nonetheless throughout the interview, Noonan elicits considered and open responses: the warm, funny, brainy Frame comes across strongly. On what provokes her stories, she says, "They arise, one uses one's feelings." Frame gives as an example a visit to a Camberwell dentist, which eventually inspired characters and plot in The Adaptable Man. "Of course one doesn't write unless one is haunted. I don't write unless ... an idea haunts me."

"When I wrote Owls Do Cry, for instance, I'd never been to bed with a man. I'd never had all those experiences I've had since ... one learns a tremendous lot by living those things."

The recent documentary Wrestling with the Angel (2004), based on Michael King's comprehensive biography, was structured around a life survey. That is not attempted here. Instead Frame's stories are used to allude to her life. Excerpts from Faces in the Water, an early collection of short stories, are dramatised, as well as Intensive Care, and another unidentified story set in America.

The dramatisations [not featured on NZ On Screen] have dated and lean a little too heavily on the supposed connection between Frame's fiction and biography. But they hint at the emotional world of Frame's characters, and the ‘ordinary' dramas that provide the tension and interest in her stories.

With a freshness, and an unhurried sense of doing justice to its subject, the framing interview in Three New Zealanders: Janet Frame avoids the familiar ‘madwoman to genius' arc and provides an intriguing moving image screen-grab of Frame's life and world, circa 1975.