War Stories Our Mothers Never Told Us

Film (Trailer and Excerpts) – 1995

A perspective

The idea for War Stories germinated in about 1986, according to director Gaylene Preston, when she noticed her mother's eyes go misty listening to ‘As Time Goes By', the theme song from Casablanca. She told her daughter that it was a special song for her during the war, hastily adding "for me and for your father". The filmmaker put two and two together when she remembered that Casablanca didn't come out until 1943, and her father was interned in a prisoner-of-war camp from 1941. There was a story there, she realised, that her mother had never told her.

Gaylene asked her friend Judith Fyfe, an experienced oral historian, if she would interview her mother about her life during World War ll. Aware of the risks of stirring up issues within a family (and with little interest in the war) Fyfe said no. However Preston's famous persistence eventually paid off, and she finally agreed.

This initial interview led, in 1993, to the launch of a major oral history project, though Preston says she always had the idea of a film firmly in her mind. Being 100 years since New Zealand women got the vote, the project was an ideal candidate for funding from the Suffrage Fund, and this (along with Lotteries Commission money) allowed them to record 65 interviews over the next two years with women who were prepared to talk about their wartime experiences.

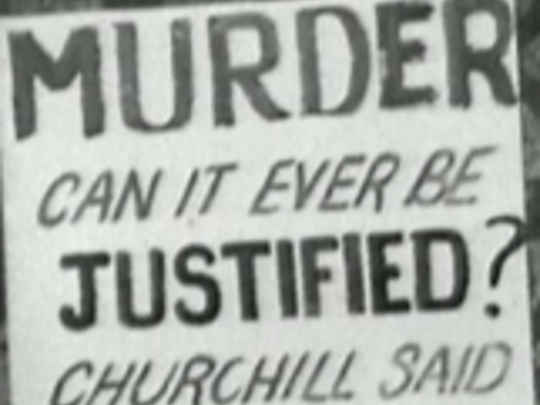

Until that time, the majority of women who had been interviewed for the historical record were nurses or servicewomen. The women Preston and Fyfe were interested in were not necessarily uniform-wearers; they wanted to know more about the small personal details than the big events. When approached, the women's response was frequently "but I wasn't at the war dear". The resulting film was an ‘unofficial version' of the war, overturning many of the myths about what women had gone through during this tumultuous time.

Raising money for the film that came out of this oral history project was always going to be a challenge, as Preston was convinced that it needed to be filmed on 35mm and recorded in Dolby Stereo. She was also aware that a film about New Zealand women talking about their WWll experiences would probably have little currency beyond this country, and with no international sales to rely on, it would be unlikely to get its money back. They were therefore not surprised to be turned down a number of times.

However some of the oral histories were transcribed and made part of an exhibition at the National Museum, and these transcriptions, with accompanying archival material, were submitted as a script to the NZ Film Commission. This time they were successful. Preston was concerned that as many of the women were elderly, there was no time to waste in getting their stories down on celluloid; in fact, she'd already begun filming some of them after tracking down some cheaper 16mm stock.

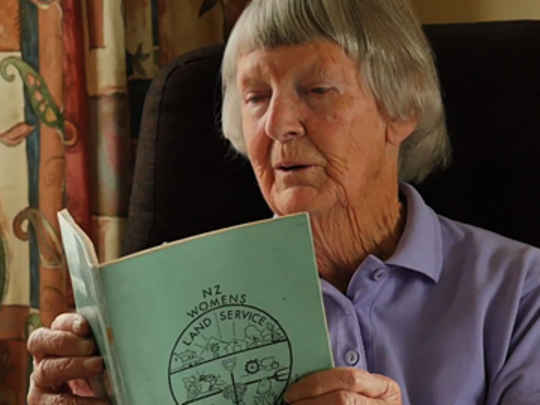

The seven women who ended up in the film were Pamela Quill, Flo Small, Jean Andrews, Rita Graham, Neva Clarke McKenna, Mabel Waititi, and Gaylene's mother Tui. They were recommended by the people who originally interviewed them for their oral histories; they were all felt to be women who had special stories to tell. When Preston invited them to participate in the film project, she expected at least half would say no. To her surprise, all said yes immediately.

From this point on, Preston made a special point of working very closely with all of the women, making sure they were fully aware of what they were getting themselves into. The film project was different in many ways from the oral history recordings, completed about two years earlier. The taped interviews were three hours long, whereas the filming was only 60 minutes— on six rolls of film, each lasting 10 minutes. They were also filmed in a studio setting, in Wellington. This was done primarily for financial reasons, as travelling a film crew around the country would have been a costly exercise. But it also allowed the interviews to take place in a neutral place, with no interruptions. It also meant the filmmakers could achieve a much higher quality sound recording, an undeniable strength of the film.

The interviews were filmed by cinematographer Alun Bollinger, in either medium-shot or close-up, in front of a black velvet curtain. Interviewer Judith Fyfe was positioned very close to the camera so that the subject's eye line was reasonably close to the lens, providing the viewer with a feeling of intimacy with the subjects.

Once the filming was completed, Preston took each interview to the families to view first, so that there were no surprises for anyone. She credits John O'Shea for teaching her about how valuable it is to take care of your documentary subjects in this way, and with such elderly subjects (including her own family) she was acutely aware of the importance of doing so for this film.

The film's credits end "in loving memory of Auntie Jean Andrews/He Tohu Aroha". Unbeknownst to Preston, Andrews had galloping lung cancer and her interview took place on the last day she was able to talk. She died shortly afterwards.

Interspersed with the interviews are clips from newsreels. Many of these tell the 'official' story. However by hunting through offcuts, Preston and Fyfe also found footage of scenes such as mothers and lovers visibly upset as they farewelled their men — as opposed to the flag waving and jubilation that the government wanted people to see.

Many popular songs of the time are incorporated, providing a very real sense of time and place along with the personal photographs and original film footage.

Reviews were uniformly positive, mostly commenting on the simplicity of the filmmaker's approach and the unacknowledged heroism of the women. The Listener referred to them as "passionate, funny and incredibly inspiring". North & South called War Stories "moving, compassionate, truthful — and powerful evidence that the strongest effects are created by sheer simplicity". The NZ Herald found "these war stories, unadorned and told with heart and soul, are mesmerising".

International journals were equally upbeat. Variety said "while its treatment is simple, the effect is profoundly moving" and The Washington Post described the film as "distinctive not only for its frankness and intelligence but also for a restraint that verges on grace".

War Stories was selected for many major international film festivals, including Venice, Toronto, Sundance, Seattle and London. It had a theatrical release in New Zealand that lasted more than five months, setting house records at Wellington's Paramount Theatre during it's first two months.

In 1995 War Stories was judged Best Documentary at the Melbourne International Film Festival; it won the Audience Award and Best Documentary at the Sydney Film Festival, and Best Film at the NZ Film and Television Awards.

A DVD was produced 10 years after the film's release. This contains an additional interview with well-known ceramicist and teacher Doreen Blumhardt, which wasn't included in the original film. She tells what it was like to be the daughter of a German immigrant who was incarcerated during the war as a possible Nazi sympathiser — even though he had been living in New Zealand for 50 years.

In 1997, the six surviving women in the film travelled to the United States for the film's release, as guests of the American Film Institute. The DVD also includes a featurette about their trip.