Whale Rider

Film (Trailer and Excerpts) – 2002

A Perspective

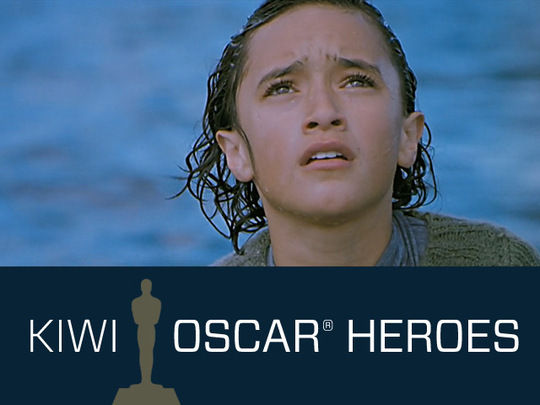

Based on Witi Ihimaera's novel of the same name, Whale Rider follows Pai (Keisha Castle-Hughes), a spirited young Māori girl who challenges her staunchly traditional koro (Rawiri Paratene) to claim her birthright and become leader of her tribe.

The title of writer-director Niki Caro's first short film Sure to Rise seems prophetic. Coupling a specific sense of place and culture with a universal coming of age story, Whale Rider met with sizeable success worldwide.

"The genius of the movie is the way it sidesteps all of the obvious clichés of the underlying story and makes itself fresh, observant, tough and genuinely moving" wrote American critic Roger Ebert. Rolling Stone's Peter Travers described Whale Rider as "a film of female empowerment that resonates deeply."

Whale Rider's journey to screen was not a quick or easy one. The rights to Ihimaera's novel were acquired by producers Murray Newey and John Barnett in the early 90s. The screenplay went through multiple drafts. At one stage Ian Mune was attached to direct.

It was almost a decade after the novel was originally optioned that Niki Caro took up the reins, under the umbrella of Barnett's company South Pacific Pictures. "I read all the previous drafts but they didn't speak to me." Caro says in one interview. She rewrote, focussing on the relationship between Pai and her koro; old and new forms of leadership.

Producer John Barnett recalls "I always believed that Whale Rider's themes are relevant to societies and cultures throughout the world. What she [Caro] did was so fantastic, we offered her the opportunity to direct the film."

Seen by over 850,000 New Zealanders, Whale Rider was also an international hit, winning the People's Choice award (from 344 films) at Toronto, and a standing ovation, and the World Cinema Audience Award at Sundance. And the accolades kept on coming. What's more, Whale Rider was a financial triumph: in the United States it made $21 million at the box office (excluding Peter Jackson's Hollywood epics, a record for a New Zealand feature). It also fared well in Australia and at home making A$8 million, and NZ$6.4 million respectively.

A New Zealand-German co-production, Whale Rider's success also lifted the New Zealand film industry's international profile. And it provided a lyrical alternative vision to the Once Were Warriors-dominated perception (gritty, violent, urban) of Māori culture.

Eight years before Whale Rider, Lee Tamahori's Once Were Warriors had unflinchingly depicted the plight of urban Māori, economically disenfranchised and dislocated from the land and their culture. What Warriors has in fire, Whale Rider has in water. Cinematographer Leon Narbey's camera is constantly swung seaward, evoking the spiritual relationship between the ocean and the Ngāti Konohi people.

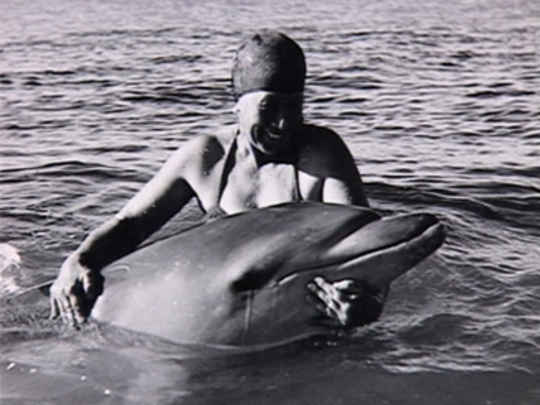

Ngāti Konohi legend tells of how their ancestor Paikea rode from Hawaiki to Aotearoa, on the back of the whale. This mythic element is threaded through the narrative. As in Warriors, the potency of a people's connection with their history and environment is the fundament of the story.

There was some resistance to Caro, a Pākehā, telling a Māori story. "The Māori have a very high bullshit detector," said Caro in an interview with website Indiewire. In order to make Whale Rider, she first needed to gain the trust of Ngāti Konohi; they had to know she could tell their story, and she needed to understand them in order to successfully tell it. She succeeded.

Caro shot the film in the small East Coast settlement of Whāngārā, the novel's original setting. Its seaside pace and Narbey's restrained palette of East Coast blues and greens, recalls Barry Barclay's Ngāti, another strong Coast story. Many of the extras and some of the smaller parts were played by local Māori. "I got nothing but incredible love and support" says Caro.

Picked by casting agent extraordinaire Diana Rowan, Castle-Hughes, who was eleven at the time of shooting, shot to international prominence for her performance in the lead role as Pai. In 2005 she was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actress. She was at that time the youngest person to be nominated in that category (in 2013 Quvenzhané Wallis was just nine when she got nominated for Beasts of the Southern Wild).

The pivotal scene where Pai performs a school speech dedicated to her Koro (Rawiri Paratene) is deeply moving. Her Koro's empty seat powerfully states his absence, and Castle-Hughes's evocation of Pai's courage, disappointment and defiance, is palpable. This is superb cinema.

Caro's efficient and assured negotiation of the pitfalls of a "feel good" story got her noticed. All the big moments are honestly won. Though her first feature Memory and Desire had won Best Film at the NZ Film Awards, and had shown at some international festivals (including Cannes), Whale Rider catapulted her into Hollywood; now a director of international renown, she was able to pull some serious star power. Her next feature, North Country, starred Charlize Theron; it was another story of someone told what she can't do because she is a female, who rises up to prove otherwise.

Whale Rider shows the confusion of a culture in transition, asks how the old ways work in with the new. It ends on a note of hope: Pai's father Porourangi's half finished waka, which had sat idle and rotting throughout the film, is launched on sparkling blue calm. Pai puts it like this:

"I'm not a prophet, but I know our people will keep going forward, all together, with all of our strength."

- Catherine Bisley is a writer and filmmaker.