Wrestling with the Angel

Television (Excerpts) – 2004

A perspective

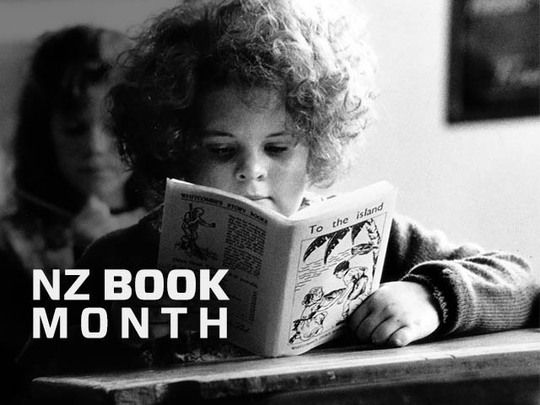

Wrestling with the Angel is a documentary based on the 2000 biography by historian Michael King, about New Zealand novelist, Janet Frame. It was made after her death in 2004. Actor Geraldine Brophy reads from Frame's autobiographies To the Is-land, An Angel at My Table, and The Envoy from Mirror City and these excerpts form the framework of the film.

The well-known aspects of Frame's life are recounted - the traumatic childhood (poverty and the deaths by drowning of two sisters); her sessions with John Money while studying at University; her breakdown, internments at psychiatric institutions, over 200 electroshock treatments and a misdiagnosis of schizophrenia; her residency with writer Frank Sargeson; her cathartic overseas migration; her international critical, then later popular (with the release of her autobiography and Jane Campion's award-winning film adaptation) recognition - but new material also emerges.

Frame avoided publicity throughout much of her life. With the exception of the 1975 documentary Three New Zealanders: Janet Frame, there is little filmed footage of Frame to draw on. Luckily she had a great capacity for friendship, maintaining strong relationships with family and friends locally and internationally.

It is these people that illuminate Frame the person - her American publisher George Braziller, sister June Gordon, niece Pamela Gordon, writers Frank Sargeson and CK Stead, friend and doctor Bob Cawley, as well as other New Zealand and American friends. Frame's sly sense of humour is a common theme: "people say ... 'Why don't you go out and mix?' - as if I were a pudding." (Frame, quoted in the King biography).

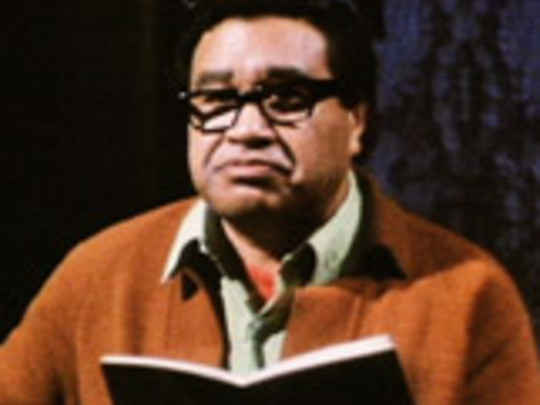

Stead talks about sessions spent bantering and joking and discussing literature with Frame at Sargeson's Takapuna house, where she composed her debut, Owls Do Cry. In an archive clip of Sargeson there's a wonderfully affectionate moment of literary envy as he recollects watching her write on a typewriter in his backyard army hut.

The interview with King in particular, provides an affectionate account of Frame's life. This was his last screen interview - he was tragically killed in a car accident in 2004, midway through the documentary's production.

That Frame escaped a lobotomy only because shortly before it was scheduled to take place she won a major literary prize, has long been an unavoidable part of the Frame story. But through the interviews excerpted here, it is mid-20th century New Zealand society that comes across as a key part of Frame's early context, as much as the fact of her near-encounter with the scalpel. 1950s New Zealand presents as a conformist, claustrophobic place, un-accepting of difference or eccentricity.

Sheila Natusch (nee Traill), a friend of Frame's and fellow teacher trainee, talks of the intense milieu at university: "the air was heavy with psychology in those years. Freud was still very much to fore, we all used to go on about complexes ... and of course, being young, we'd wonder if we had all these things the matter with us."

Frame had become infatuated with Money at the time of her breakdown, and King raises the intriguing possibility that things for Frame might have "worked out rather better" without Money's influence at this time. Contrary to common belief, Money, was not qualified as a medical doctor or psychiatrist - he was her psychology tutor and was roughly the same age as Frame when he was counseling her.

The importance of Frank Sargeson as a mentor is conveyed (Sargeson befriended Frame after she was released from Seacliff Asylum). In excerpts here, he is seen empowering Frame's belief in the world of words: "you don't have to be something else and a writer in your spare time ... just, be a writer," and he establishes the importance of routine and of "forming, holding, maintaining our [writerly] inner world."

Director Peter Bell and cinematographer Wayne Vinten both have long resumes of television programmes to their name - documentaries in Bell's case, and both drama and documentaries in Vinten's. Wrestling with the Angel was the first arts-related subject for them both.

Sometimes this documentary's framing narration falls into the trap of aping well-trodden Frame myths (the mad-woman to genius stigma), summarising her life into broad telly-friendly bites. This is apparent when covering her period at university. Frame is described as finding emotional outlet "only in writing", then shortly afterwards the narration states that her psychology course with Money was her "only escape from her increasing alienation."

But King et al are able to colour one of the central questions of Frame's life - how a shy person gifted with a unique ability to express her interior world in words, overcame misunderstanding to become "New Zealand's greatest writer" (Rachel Cooke, in a 2008 Guardian review of Frame's Towards Another Summer).

Clarifying the perception of Frame as reclusive (Frame was described in Time magazine as "an antipodean J.D. Salinger"), Scottish writer Elspeth Barker talks of the awe with which Frame was held amongst their group of bohemian writers and artists: "she just couldn't tolerate insincerity or hypocrisy ... she just used her capability to be withdrawn as her protection ... she didn't put on anything else. She could be very silent. Thinking. I never felt that she was staring out of a window vacantly. [She was just] always thinking."

Director Jane Campion wrote, with regard to Frame's life story, that, "a poetic soul has rarely come better disguised." The remembrances in Wrestling with the Angel are illuminating essays at disarming that disguise. Frame's fiction often deals with the construction of reality ("the magic of words"); she laid out her own identity road-map - self-conscious, but typically eloquent - in the well-known words that begin To the Is-Land:

"From the first place of liquid darkness, within the second place of air and light, I set down the following record with its mixture of fact and truths and memories of truths and its direction toward the Third Place, where the starting point is myth."