The Merata Mita Collection

The Merata Mita Collection

This collection has three backgrounds:

Life and Art Intertwined

Keeping the Promise

A Journey around Merata

Life and Art Intertwined

By Heperi Mita 30 May 2024

When it comes to releasing a collection of Merata Mita’s works, life and art are intertwined. Her political and personal struggles manifest not only within the content she made, but in the very process of compiling her films to make them publicly accessible. You need look no further than her very first television appearance as an example.

Māori Women in a Pākehā World (1977) is a restricted item from the TVNZ archives that, until now, has not been publicly accessible. As one of the subjects of this documentary, Merata speaks candidly about her own personal experiences with abortion and exploitation, in an emotional interview about the hardships of city life as a Māori woman and solo mother.

The first time I saw this piece was one of the few times I ever shed tears while researching my mother’s work, and there is a part of me that would prefer for this item to remain restricted.

But almost 50 years after it was first recorded, there is an enduring truth to that interview that remains as just relevant now as it was then. There are many today who continue to suffer the same plight as she did. For this reason alone it must be made accessible — not merely as a historic record, but for its potential to inspire hope.

The raw honesty exhibited in that interview would set the tone for the rest of her career — making her work noteworthy, but also sometimes difficult to access.

This is embodied most dramatically in her landmark documentary Patu! on the 1981 Springbok Tour, the film that defined her career. While it won its share of newspaper headlines, Patu! was made at a time when documentaries rarely screened in New Zealand cinemas. The dominant cinema chains, Amalgamated and Kerridge Odeon, showed no interest. Patu! played in independent venues, and many international festivals; it wouldn’t be televised for another eight years. However it has long been part of NZ On Screen’s catalogue, and its place within this collection is inevitable.

Unlike Māori Women in a Pākehā World, there is very little of Merata in Patu!. Her stylistic preference in all of her documentary work was to let issues unfold for the audience, with her presence minimised to brief narration on political or historical context.

Beyond the films that she made herself, programmes made by others that profile her and her work provide fascinating context. Close Up - Patu: Completing the Picture (1983) reveals the toll Patu! took on her and her family, and more broadly examines the burden she carried of making controversial and challenging work as a filmmaker.

"What you're fighting are these kinds of entrenched attitudes that come from people who control money in the film industry . . . you become very angry, because it’s an unfair fight, and a lot of your energy that can be going into making a fantastic film, a better film, a much more deserving film, is being diverted into fighting these institutions."

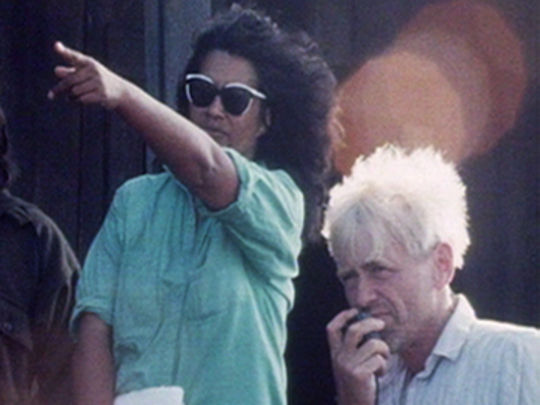

Merata Mita and her son Heperi. Heperi would later direct documentary Merata: How Mum Declonised the Screen

These battles sharpened her mentality, influenced her career and have shaped what can be included in this collection.

The rights to much of Merata's early work were often shared with collaborators and institutions, and while these arrangements were usually amicable, she also felt that they were at times imposed on her. In interviews she often commented on the institutionalised racism and misogyny within New Zealand’s film industry that prevented her from obtaining funding and hiring equipment as a Māori woman.

It was these battles that helped drive her desire for story sovereignty. But, there were also tikanga frameworks that guided her.

Her two most significant works from a purely Māori perspective are arguably her 1990 documentary Mana Waka, an archival film using footage shot in 1937 that documents the construction of three waka taua commissioned by Princess Te Puea Hērangi, and Bastion: Point Day 507, which captures the forcible eviction of Ngāti Whātua from Takaparawhau in May 1978.

While these projects are not without their own controversies, a major factor in their omission from this collection is their status as taonga to the respective iwi that they document, and their public exhibition is rare. The ongoing kaitiakitanga of these taonga is part of a lasting agreement that was integral to the creation of these films, and embodies Merata’s Māori worldview and approach to filmmaking.

The most lamentable omission from her screenography — although I'm glad it is in this collection — is Cousins. From the release of Patricia Grace’s novel in 1992, to her twilight years, Merata dreamed of writing and directing a screen adaptation. She spent countless hours scripting and submitting funding proposals without success. The rejection was disheartening and a source of prolonged frustration.

In 2021, 11 years after her death, Merata's vision was finally realised by two of her protégés: Ainsley Gardiner and Briar Grace-Smith. And although that film does not appear in her official screenography, it is a representation of the greater legacy she left. The list of indigenous filmmakers, both in New Zealand and internationally, that she mentored and/or influenced is illustrious. The battles she fought — even the ones that she lost — have helped to pave the pathway for the generations that have come after her.

In this way, the Merata Mita Collection can only encompass a fraction of her work. The ongoing, living legacy of creatives and mahi that she continues to inspire has a whakapapa of its own.

- Heperi Mita (Ngāti Pikiao/Ngāi Te Rangi) began making feature documentary Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen during a nine year stint as an archivist at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision. In mid 2020, he joined NZ On Air as a funding advisor.

Keeping the Promise

By Ainsley Gardiner 30 May 2024

As I write this on Mother's Day 2024, I'm thinking about Merata. I've heard her described as the godmother of New Zealand film. I've met all of her adult children, and I know how beloved, if sometimes tough, a mother she was. My favourite image of her, which she herself described, is of Merata preparing dinner for her young children whilst living and teaching in Kawerau: stirring the pot on the stove and reading, an open book perched above the hot elements.

Merata Mita in 1977 documentary series Women.

It captured for me the image of a woman whose role as mother only strengthened her capacity and determination for other endeavours. As a mother who struggled to embrace the job, and who always longed to be making films, not school lunches, that image was an early inspiration for me. She was a mentor to many around the world. Many of us must think of her as I do, as a mother of a kind.

I met Merata first through her films, while I was studying film in the 90s. When writing about her for an essay, I was encouraged to speak with her directly. That was a no from me — even then, I was intimidated by the idea of her. Seeing Merata on screen in Utu and Bastion: Point Day 507, the sheer beauty of her, the power, her articulation of te reo Pākehā, her passion for te ao Māori, were more than intimidating — she was an enigma to me, because she was so different to anyone I’d ever encountered.

Merata Mita as Matu in 1983 movie Utu.

Once I came to know her, Merata taught me many things. She taught me that filmmaking could be a political act. When making Mauri, she prioritised the hiring of local Måori over more experienced crew, which many would see as a creative compromise. It is a principle I hold to still. She taught me that filmmaking is a privilege. She taught me that not everyone is in a position to do it, and if I was fortunate enough to be able to do so, then I should stop being a little baby and get over myself.

She was renowned for telling it like it is. The aforementioned telling-off was one of only two times I saw that side of her; at all other times she was so kind to me. She knew I was vulnerable and uncertain about my place in the world, my place in the industry, and my place in te ao Māori. I think she also knew I was essential to the industry, as one of only a few wāhine Māori producers getting films made at that time. I'm certain that her nurturing of me was just one of the ways she worked to build the industry she loved and long championed.

In 2004 I was invited to attend a Māori directors hui in the Coromandel that she ran. We had to make a short film and edit it. Heperi, her youngest son, 18 at the time, and I worked long into the night, editing the short I had directed. We were delirious and behaving ridiculously, giggling and being disruptive and childish. This was the only other time I was chastised by Merata. She chastised me on both occasions as if I were a child, and I didn't mind that at all.

Even at 30, and a mother myself, I appreciated her mothering so much. It helped me survive in an industry which at that time (and sometimes now) could feel like a lonely place to be as a producer, as a young woman, as a Māori. I was also aware that she saw my potential beyond producing. She was certainly the embodiment of the multi-hyphenate: mother-writer-director-producer-mentor-etc.

On location for Geoff Murphy's The Magnificent Seven (1998).

I always wanted to be a writer/director. I fell into producing, when the film and TV course I was attending secured a work placement for me with another pioneering Måori filmmaker, Larry Parr, at Kahukura Productions. I think the quality Larry always admired most in me was my common sense. In 2005 Merata, Larry and Cliff Curtis sat me down at the inaugural Wairoa Film Festival when I was worn out, and again ready to quit the industry (it had, in my opinion let down my mentor, Larry — but that’s another story). I won’t say they forced me to hang in there, but me versus Mita/Parr/Curtis was never going to be great odds.

In the years that followed Merata was there for me. As I said, she was renowned for her ability to tear you a new one. I never experienced that. I understand much more now — the more I came to terms with how to be both a mother and a filmmaker — how much effort it took for her to give me that patient, encouraging side of her. And how important it was to her that I stay in the industry: that I find my own way to encourage and support other wåhine Måori producers to stay and keep working, ahakoa mo ngā piki me ngā heke!

We sat on Te Paepae Ataata together from 2007. She showed me how the principles of tikanga can and must be enforced in our processes, in order to strengthen te ao Māori and te āo whakaari Māori. She held us all on that paepae accountable to the highest level. I don’t think there was ever a time we could disagree with her point of view — it was always well-considered, crystal clear and laser-focussed. Her ability to be quiet and deadly is one I still aspire to, and fear I will never master.

In 2009 we made Boy. It was during that time that I got the other telling-off from her, when Cliff Curtis, another of the producers who was making the film with me, and I were at odds. She called us babies, and I once again felt the iron fist (albeit velvet-gloved in my case) that others were more familiar with. I appreciated her even more because of it. For the record we were being big babies, and we did, in the end, get over ourselves, but having a rangatira and a māmā deliver the blows was what made it possible for us to do so.

A few months before she passed away, Merata emailed me about succession planning on the Paepae. It worried me because we needed her, but also because it spoke to the fact that she was starting to weary. I suspect this happened to her many times in her life and career. But I had never seen her mana and power, and her energy, waiver. I was both surprised and not when we got the news of her passing. It has truly been an impossible loss to recover from.

A scene from acclaimed 2021 movie Cousins, directed by Ainsley Gardiner and Briar Grace-Smith.

I often play WWMMD — What Would Merata Mita Do — when making tough decisions in my career. I'm acutely aware that I almost never can do what she would do; I wasn't forged in the same fire. She would remind me that my way was my way, and hers was hers. She taught me that the best thing I could do, for myself, for my family and for te ao Måori, was to be successful in our industry. This was one promise that I could keep for her.

In 2013 I was also able to complete production of The Pā Boys — the first and only movie from Te Paepae Ataata — which Merata had been producing. And then Briar Grace-Smith and I were able to bring Merata's passion project Cousins to life. It may not have been Merata's vision for the film exactly, but I hope it was done in a way that would have made her proud. I am grateful to Merata’s family, who shared their mother with the world. She was a mother like no other, and a mentor who helped shape the course of my life.

- The list of producing credits for Ainsley Gardiner (Te-Whānau a Apanui, Ngāti Pikiao Ngāti Awa) includes Oscar-nominated short Two Cars, One Night, and movies Boy, The Pā Boys and The Breaker Upperers. She co-directed Cousins and anthology movie Waru.

A Journey around Merata

By Tainui Stephens 30 May 2024

We have many Māori pioneers in film. In every era someone is doing something for the first time, and forging a new pathway. But there are only three eponymous ancestors in our film whakapapa — three rangatira who first made Māori film happen.

Despite the hostile era in which they lived, Barry Barclay, Don Selwyn and Merata Mita became giants. Their intelligence, savvy and bravery reflected their need to make films that make us a better people. They created a template for indigenous screen storytelling.

I knew Barry and Don well, but I never worked with Merata. From the 90s we connected more frequently, if she was in the country. I journeyed around her, rather than alongside her. But we were heading the same way. She was in front, but always had time to slow down and give you directions. You listened, because Merata lived a big, worthwhile life.

Merata Mita during a 1984 Koha interview.

Merata's childhood in the Bay of Plenty was one she recalled with fondness. She was shaped by the tikanga and whānau dynamics of her Te Arawa people. She became a teacher but was concerned about poor achievement amongst Māori pupils. But she was excited by their artistic abilities, and the stories they explored with the early audiovisual technology.

In the 70s, Merata flexed her filmmaking intuition and skills. She saw screen stories as a way to express the burgeoning Māori consciousness of the times. In 1972 Ngā Tamatoa set up a tent embassy at Parliament. They kicked off an era of protest, which created a movement of thinkers whose ideas would change the nation. Merata was in the thick of it all.

On 25 May 1978 I was working as a barman at the South Pacific Hotel in Auckland. I looked at the small television in the public bar and watched long lines of cops descend upon Bastion Point.

On that same day Merata and her hoa tāne Gerd Pohlmann, alongside Leon Narbey, had answered a call to film the eviction of Ngāti Whātua and their allies, from the long-running protest occupation at Takaparawhā. I stood behind that bar, stacking jugs, as tears rolled down my face. I feel that same sadness today when I watch their poignant film Bastion Point: Day 507.

In 1980 I moved from Christchurch to Auckland to connect further with my whānau and tribe. I was hungry for any chance to hear and learn te reo Māori. I went to as many hui as I could. My girlfriend and I made kapa haka a part of our world.

Our club in Manurewa practiced on Sunday afternoons. I soon got into trouble for missing club practice. I had discovered the television programme Koha. I was blown away that so many of the things I sought in the Māori world — kōrero with elders, waiata, histories, and current events, were now (briefly) on TV.

I was such a fan. And one of the reasons was the presenter, Merata Mita. She was a compelling presence in an era when TV presenters smiled, or winked, way too much. She was a luminous presence: her beauty was apparent, but the eyes told a different story — which became clear as soon as she spoke. Merata was proudly Māori. Sometimes that meant feeling her impatience and anger, when she spoke of injustice.

Merata was at odds with a 'soft' programme like Koha. It was framed as a window on the Māori word for a Pākehā audience. Merata wanted we Māori to tell stories to ourselves, the kinds of stories that would challenge an obstinate status quo.

During the tumultuous Springbok tour of 1981, I was working for the Office Of The Race Relations Conciliator. The clashes between police and a coalition of protestors divided the nation. I couldn't be seen to be part of "serious protest action", but I could go on marches. I always felt safe.

Merata's film Patu! hit me like a body blow; but nothing like those suffered by braver protesters. Patu! is visceral. It gives a street's eye view of the brutality, and the culture that spawned it. Merata and editor Annie Collins encountered legal obstacles and police harassment as they finished their film. Patu! remains a blistering cinema experience.

Merata said "My perspective encourages people to look at themselves and examine the ground they stand on".

I first met Merata at a screening for her and Martyn Sanderson's Keskidee Aroha, a documentary about the touring black theatre group from London. I had a discussion with her about Utu, an upcoming movie about the New Zealand Wars period. Being a fan of Māori on TV, I had huge hopes for our stories on the big screen.

Merata Mita as Matu in 1983 Geoff Murphy movie Utu.

I'd been impressed by Merata's performance in the television adaptation of Rowley Habib's play The Protesters. She'd played a staunch activist who in one scene expresses outrage at the sexist and violent ways of Anzac Wallace's character. When Merata yells at him "You shit on your own kind Manny", I felt the fury and the sting. I knew she would bring something powerful to Utu, and so she did. In the role of Matu she demands the right to kill Anzac Wallace, this time in his role as Te Wheke, the warrior gone bad.

The memorable characters, sheer drama and gusto of Geoff Murphy's frontier tale made Utu an immediate classic. It was a clever mix of genre and revisionist history, a puha western with meat.

I was inspired by the Māori screen stories I had been exposed to. In 1984 I joined Koha myself. Merata had left the show by then, but I started to learn, from whoever I could.

These giants of film, Baz and Don and Merata, were shaped by their Māori souls and consciences. They shared the wisdoms they'd accrued from decades of struggle and achievement.

Barry said "The camera must always have good manners". Respect counts.

Don said "Ko te kaupapa kei mua. It's not about you!" — Humility counts.

One of Merata's pearlers came about like this: in the early 90s, a bunch of us went to Merata's place in the Coromandel for a film directing workshop. I was so excited. Merata and Geoff were both living overseas, so it was a rare opportunity. We got a fascinating week of insight into film, and Merata and Geoff were brilliant hosts.

On the last night, we celebrated the end of our course. We partied up. In the morning, we staggered into our workplace. It was a tip. Bottles and cold kai and ashtrays everywhere. We slumped into our bean bags. Then Merata walks in. She casts a quick look around and erupts. She bollocksed us big time for our filthy work space. Her furious words echoed around our ears. "You want to be directors, when you can’t even clean up after yourself? You fellas have gotta learn to clean up your own shit!" Professionalism and a tidy mind counts.

A kōrero about Te Paepae Ataata, in 2007/8: From left, Graeme Mason (Chief Executive of the NZ Film Commission), Ainsley Gardiner, Renee Mark, Tainui Stephens, Merata Mita, Kath Akuhata-Brown, and Hone Kouka (NZFC).

In 2007 I met with Barry and Merata to discuss a new way to fund Māori films. Our Te Paepae Ataata concept created a tikanga-based context for indigenous film development and funding. Thanks to an apparent lack of funds, only one film was made: Himiona Grace's The Pā Boys. However, I was so happy Merata was now living back in Aotearoa, mentoring a new generation of Māori filmmakers like Ainsley Gardiner, Briar Grace-Smith, Taika Waititi, Tearepa Kahi, Chelsea Winstanley, and Kath Akuhata-Brown.

When I meet indigenous filmmakers from around the world, so many of them were inspired by Merata's mana and love. She established an indigenous film programme at the University of Hawaii. Her rigorous intellect, formidable presence and body of work saw her in demand at festivals, conferences, and workshops. Merata was a born teacher. She gave of herself and shared what she knew with anyone she viewed as sincere and genuine. But not so much with evident fools.

Many recall being on the receiving end of Merata's ire. She once ripped into me on the phone. I'd made a programme that included some footage from Bastion Point: Day 507, but didn't credit her name on screen. I'd put her name in the credits at the end, alongside the other filmmakers. That didn't stop her from using a line straight out of The Protesters, when she accused me of "shitting on your own people!".

I survived the call but wasn't looking forward to the next week. We were both giving a talk at the Police College in Porirua. I turned up, but she didn't. It appears she used the travel and the accommodation, but didn't turn up at the gig. I was pleased to have missed her. But I had a niggling feeling she'd let the side down.

It was sometimes like that with Merata, Baz and Don. They could piss you off because of what they chose to do, or not do. But they were legends in their own lifetimes. I saw so many expectations being placed upon them — because the need was so great. Their lives, for all their enduring contributions, were not easy. Nor was it so for those who loved them. Only Merata's tamariki — Rafer, Richard, Rhys, Lars, Awatea, Heperi and Eruera (E moe) — know the costs of all that came with their beloved mother's life.

In 2018 Heperi directed a biographical feature documentary, Merata: How Mum Decolonised The Screen. It's a powerful testament to a consequential life. Family pains and pride are laid bare, alongside the story of a mother who was often absent to ensure the voiceless had a voice.

On 31 May 2010, Merata died doing just that. She passed away in the arms of editor Rāhera Herewini-Mulligan at the Māori Television Service offices. Merata was working on Saving Grace, a documentary about Māori ways to prevent violence against children. She considered it her most important work.

Merata was a filmmaker who dared to explore. Her film Mauri was a penetrating drama of a man haunted by his past, and his connections to a small community. It's full of a new visual vocabulary that reflects the Māori psyche. It's indigenous cinema that gets better with age.

In the course of her life Merata made us see the screen anew, and she left clues about how we should frame the work. She once said that whenever we view archival footage of our people, we witness "resurrections taking place". All of Merata's work is now archival, and when we see it, she too is resurrected in our minds and hearts.

Any revival of Merata's work, who she was and what she did, brings to life the moving final words in her son's film: that in the end it was all about "a mother's love".

Moe mai e te whaea, nāu ka tāria te moko o tuawhakarere ki te kiriata Māori.

- Nā Tainui Stephens, Ōtaki Beach, Haratua 2024

- Tainui Stephens [Te Rarawa] began his screen career on TV show Koha. His work as director includes award-winners Waka Huia and The New Zealand Wars; he wrote 2016 documentary Hautoa Mā! The Rise of Māori Cinema.