John Clarke - The Collection

John Clarke - The Collection

This collection has six backgrounds:

Twelve Short Tributes, and some Trevors

The Role of a Lifetime

The Rise of Fred Dagg

A Beloved Extra Brother

"We Need Some Women Writers!"

Bryan Dawe on Life without John Clarke

Twelve Short Tributes, and some Trevors

By Friends & Fans 22 Jun 2021

Cal Wilson on Believing in Fred Dagg

As a kid, I utterly loved, and believed in, Fred Dagg, and was shocked to find out he was a man called John Clarke. As an adult, reading his poetry for the first time, I remember laughing out loud, and thinking “Oh! You can do this with comedy.” He inspired me to explore comedy in different ways — to play with language more. He did such wonderful things with words. Everything was so deadpan, effortless, and understated. Every character was written with absolute certainty, and just a hint of suppressed glee.

I never had the honour of meeting John Clarke, but he always loomed large for me. I knew people who knew him, which felt a bit like knowing people who knew the Beatles. Nothing to personally brag about — but exciting to be just one step from greatness.

Rhys Darby on a Brilliant Kiwi

John Clarke, in his many guises, has inspired me greatly. The raw, natural spark in his character portrayals seemed so ahead of its time at the time. After watching the comedy greats on BBC TV, it was so empowering to see that a Kiwi was just as brilliant, if not more so. This was so important for our cultural confidence in the comedy world!

Fred Dagg and the Trevors, Whitemans Valley, 1974. This photo was taken by director Murray Reece during the making of Dagg's 1974 Country Calendar episode. Photo used with the permission of Murray Reece.

Michèle A’Court on Comedy in Her Own Accent

Fred Dagg arrived in our house through our TV screen in 1975, and immediately took up residence on our radiogram where his debut album, Fred Dagg’s Greatest Hits, settled in on high rotate. The record sat conspicuously between dad’s jazz albums and my older brother’s growing Bowie collection, offering a place where the whole family could meet. We all knew all the words to everything – I can still hear my father singing along, word perfect, to 'We Don’t Know How Lucky We Are', taking particular pleasure in the line "We don't know how propitious are the circumstances, Frederick". Raised on comedians like Irishman Dave Allen and American Danny Kaye, this was the first time (at age 13) that I’d heard a comedian with an accent like mine, talking about people I knew. Pretty sure we had an actual Bruce Bayliss who lived down the road and no one could convince me Dagg’s stories weren’t about him. Even now, whenever I meet anyone called Bruce, I automatically sound the name out in my head: B-R-U-C-E.

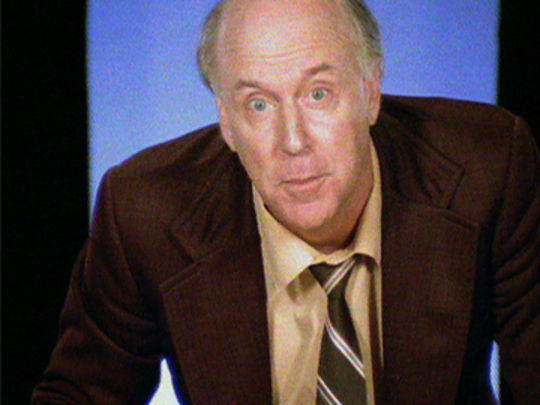

John Clarke in TV special A Bit of a Dagg (1977).

I didn't just sing the songs, I learnt the monologues — there are bits of "Education" I can still recite word for word, more than 40 years later — and performed them (badly) at home and at school. It’s where I started to learn the rhythm of comedy, the setting up, the turning back on yourself, the building up and dropping down to a punchline. Taking the piss out of something or someone, while also paying respect.

There was so much more after Fred Dagg of course — and I will always be sorry it had to happen in Australia, rather than at home — but I watched Clarke & Dawe on my computer, revelled in The Games, read all the books. We made John Clarke the patron of the NZ International Comedy Festival back in the 1990s, in the hope, I think, that one day he would come over and star in it. That didn’t happen, but he sent regular messages of support and kept an eye on what we were doing. I am madly sorry that I didn’t ever meet him, but suspect I wouldn’t have known what to say if I did. Except thank you for giving a small girl from a small New Zealand town the idea that we were allowed to be funny, in our own voice.

John Banas on Working with 'Clarkie'

I worked with Clarkie for many years. We wrote together and performed together on stage in late night revues, as well as on TV, in Buck House. To say he was a comic genius is to understate not just his abilities but his very way of being. Still, understatement was one of his great skills and Fred Dagg (who was born in those late night revues, along with Ginette McDonald’s Lynn of Tawa) is a great example.

John Clarke in series two of sitcom Buck House (1975).

My fondest memories of John are from our stage work. Writing, rehearsing as little as possible, "to keep it fresh". "Comedy works quite well if you’re pooing your pants", he said to me once. I’m sure he never did.

Sometimes, his wit got the better of him — to everyone’s great delight. For instance — we’re doing a sketch in which the dialogue consists only of the letters of the alphabet, in the requisite order. At one point I'm saying the letter "T", while pouring a cup of tea — which was, one night, very weak. John can’t help but say "Looks like your weasel’s got diabetes", then after a perfectly timed pause, "and now I’ve fucked the whole sketch, haven’t I?" We finished it there that night. Only six letters to go, and we couldn’t stop laughing. Then there was a sketch between two abattoir workers, cutting cysts out of livers, when John suddenly came out with the (unscripted) line “Did I tell you I’ve been invited over to Perth to conduct the Shostakovich Festival?" I had to leave the stage.

These are memories that still make me laugh today. But my greatest recollections are of Clarkie’s warmth, humanity, and genuine interest in people. His comedy was the result of keen and open-hearted observation. That capacity is a kind of genius of its own.

Jools and Lynda Topp (The Topp Twins) on John and Ken

A few years back we were performing in Melbourne at the arts festival, and we received a call from Mr John Clarke asking if we would like to have dinner with him. Funnily enough we had never met John in New Zealand, so we jumped at the chance to finally hang out with the man called Fred Dagg. We instantly got on like a house on fire, and he mentioned that his favourite characters we played were Ken and Ken. He noted that Ken Moller, Lynda's character, smoked a roll-your-own cigarette and that her fingers were slightly cupped whenever she held it in her hand — a gap that would allow a seven ounce glass of beer to fall out out of the sky and nestle perfectly beside that racehorse roll-your-own (a term for a very thin cigarette). After meeting John, we realised he knew more about the Kens than we did and this observation about a character who he didn't even play made him the genius that he was. We will always remember that night out fondly. It was our one and only encounter with John — but he was definitely part of our comedy family.

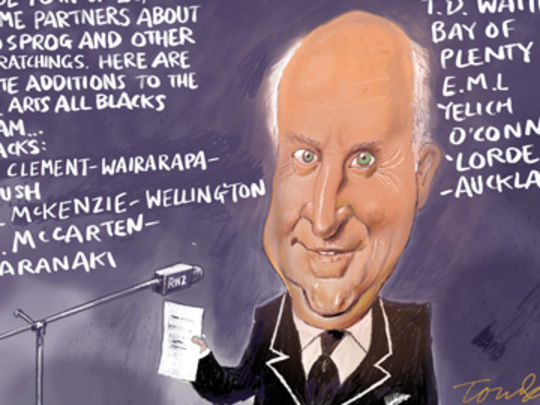

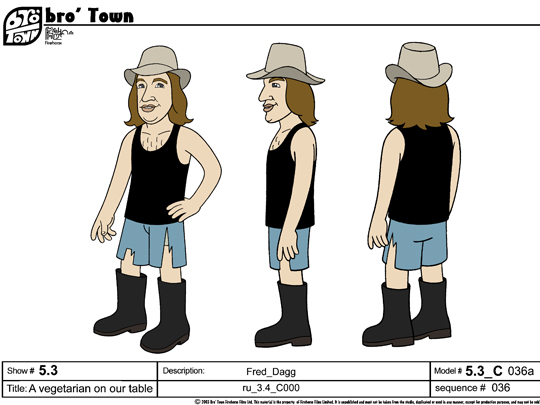

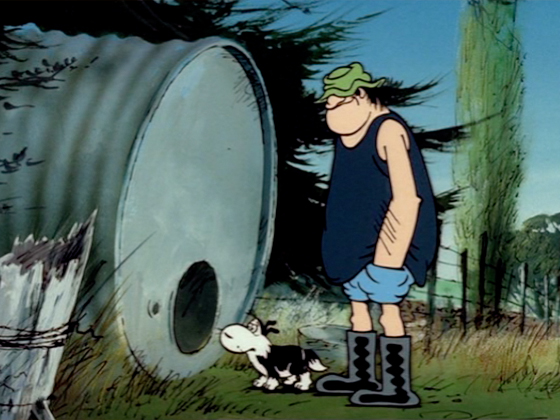

Fred Dagg concept art, for TV series bro'Town (2009).

Oscar Kightley on a Great Kiwi Export

John Clarke is New Zealand's greatest export. We can do pretty much anything to Australia now and they can't do anything about it because they got to enjoy the genius of the godfather of New Zealand comedy for ages. And he was such a beautiful soul.

Helene Wong on Acting in University Revues

In the 60s, Victoria University capping revues — Extravaganzas — were distinguished by a cast of thousands, male ballet, crude sexual innuendo and females strictly as decoration. I was a newbie in Extrav ’69, as was a quietly erudite arts major named John Clarke. When he performed solo, impersonating race caller Peter Kelly and gospel singer George Beverly Shea, he wasn’t just hilarious. He was different — droll, satirical and confidently channeling a New Zealandness at a time when cultural cringe still ruled. And he had presence.

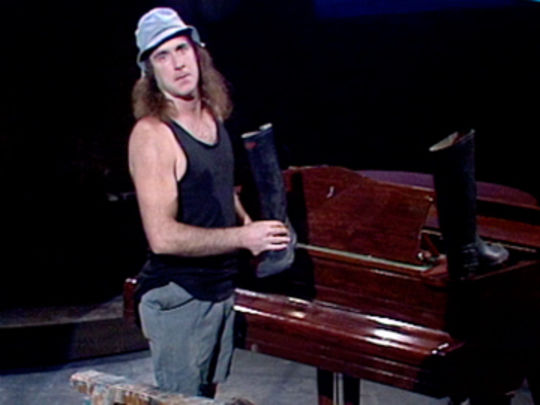

Two years later we worked together on One in Five, a revue hastily cobbled together when that year’s extrav fell over. Roger Hall, Dave Smith and Cathy Downes made up the rest of the five. To our surprise it was a smash, with repeat seasons and an album. This was in no small measure due to John; it was here we witnessed the genesis of Fred Dagg, in the form of a gumbooted and black-singleted Farmer Brown with a secret ambition to be on TV (as indeed came to pass). It was clear even then that a comic genius had arrived.

As much as I remember falling about over his performances, my strongest personal memory comes from a few years later: John, now famous, deliberately weaving his way through the rows of seats in the dress circle of the St James at some show I now forget, coming over to shake my hand as a former fellow performer. A genius, and a generous one.

Tom Sainsbury on Turning up the Dial

John Clarke is my hero, and has a career I want (or will at least try to replicate). I was introduced to John through him voicing Wal Footrot in Footrot Flats: The Dog’s Tale. Wal was some of my first comedy inspiration — what a character! I loved that he was just like the men my farmer father would hang out with. Shortly after I was introduced to Fred Dagg, firstly from singing 'The Gumboot Song' at school and then on his Country Calendar episode. As with all his characters, John takes what already exists in reality and just turns up the dial. I try to create my characters with that same truthfulness. Much later I watched his work on A Current Affair and was blown away. His character’s evasiveness to answering questions was both hilarious, and spot-on satire. It’s that kind of commentary, especially with a political bent, that I’ve become obsessed with. So yeah, John Clarke is a comedy hero and his work has inspired me indelibly. What a guy.

Wal & Dog in film Footrot Flats - The Dog's Tale (1986).

Tom Scott on Actors Who Improve the Words

The greatest satisfaction you can ever have as a dramatist is hearing your lines coming out of the actor’s mouth, exactly as you heard them in your head. The supreme delight — the icing on the cake — is hearing the lines better than you ever imagined them sounding. Mike Minogue did this, playing a cop in Rage. Beyond that treat, you get Grant Tilly's sublime performance as Danny Moffatt in play The Daylight Atheist, and John Clarke’s magical Wal Footrot in Footrot Flats (the movie). I was pleased with Wal’s half-time pep talk to his team when I wrote it, and over the moon after John worked on it — it was just fabulous.

Robert Burgess on a Friend and Fellow Rugby Player

When I was in my last year at primary school, my family moved from New Plymouth to Palmerston North. Often new kids are picked up by desperate outsiders, but I was lucky enough to be befriended by John. We were in the same class at College Street School, and also went to Sunday School together at St Andrews. John invited me around to his place in Milverton Avenue, just around the corner from school. The wall above his bed contained an awe-inspiring collection of books and comics.

We played rugby together in the College Street A team — him halfback, me at first five-eight. We knew we were the crucial hinge in the team. We feared having to play against Terrace End, because they had Basil Bridge, who we knew from Sunday School. Basil was lightning fast. All they had to do was get the ball to Basil, and he’d score.

John moved to Wellington. He was gone, forever. However, we followed each other’s careers. Thirty-five years later he rang. Both Basil and I were back in Palmerston North. Basil was dying. I’d visit Basil, and the next day John would ring. When Basil died, the calls slowed down.

A couple of years later, he wrote to me under the letterhead of The Office of the Prime Minister of Australia to convey a message of advice and support for my mayoral campaign.

We stayed in touch, always by phone. We found that ecological restoration was a mutual passion. He called me in late January 2017. He suggested ways that my restoration trust could be better supported financially. He had a friend, another Palmerston North old boy, a rich-lister who he would introduce to me.

He was a great talker on the telephone. I’d spoken to him just a month before he died so unexpectedly. His kind good heart gave out while he was tramping. In the weeks after, the press was contacted by the dozens of other New Zealanders he’d spoken to that month. He had such a talent for friendship. Everyone’s friend, yet he made you feel that you were special.

Poet Bill Manhire on Perfect Pitch

The key thing about John Clarke and poetry is that he seems to have had perfect pitch. The only other New Zealand writer who could match him is Lynley Dodd. Maybe, on a good day, Allen Curnow. Clarke’s parody project — Australianising famous poets — sounds fairly straightfoward, as in the names and biographical notes he devised for Sir Don Betjeman, Very Manly Hopkins, Warren Keats, Emmy-Lou Dickinson, BB Hummings, and others. In practice the results are much more various and nuanced. The satirical shop-front allowed him to sit out the back writing real poems without seeming to do so. In the Sydney Review of Books, Gabrielle Carey quotes Clarke saying that in his writing he was "just dealing with the language I was given in a little brown envelope in Palmerston North in 1949". That’s the sort of self-deprecation you'd expect to hear from plenty of New Zealand poets of his generation. It’s no doubt part of what he meant by "tinkering".

His parodies include a good deal of wicked mockery. Leonard Cohen and Kahlil Gibran get quite a thumping. But in the best of them empathy rules. As Clarke himself said, he’s in the business of collaboration. There’s his reworking of Dylan Thomas, 'A Child’s Christmas in Warrnambool', as magical in its Aussified way as the original. He does a lovely homage to Seamus Heaney, under the guise of Hamish Sweeney. Carey recalls Clarke saying that he became a Heaney groupie when their paths crossed at the 1994 Melbourne Writers Festival. "I went to all of his readings. I’d never heard readings like them. They were breathtaking." Heaney and Clarke had a beer. "It was an absolutely luminous period for me . . . like a wonderful shipboard romance."

There are several other stand out poems. One is attributed to Fifteen Bobsworth Longfellow. It’s a sort of instruction manual for assembling a store-bought kitset contraption, done in the Hiawatha metre. It could easily be read as a statement about Clarke’s own craft. After 18 "Do this, then do that" lines, the poem ends with the advice to "Pack up tools, retire to distance,/Don protective hat, light fuse". Another poem, 'The Track Less Thrashed', takes on Robert Frost’s well-known anthology piece, 'The Road Not Taken'. Clarke gives us a deadpan critique of the original. His poem is especially wonderful if you know your Frost, but it’s wonderful anyway. Perfect pitch, and perfect pacing. Try reading it aloud.

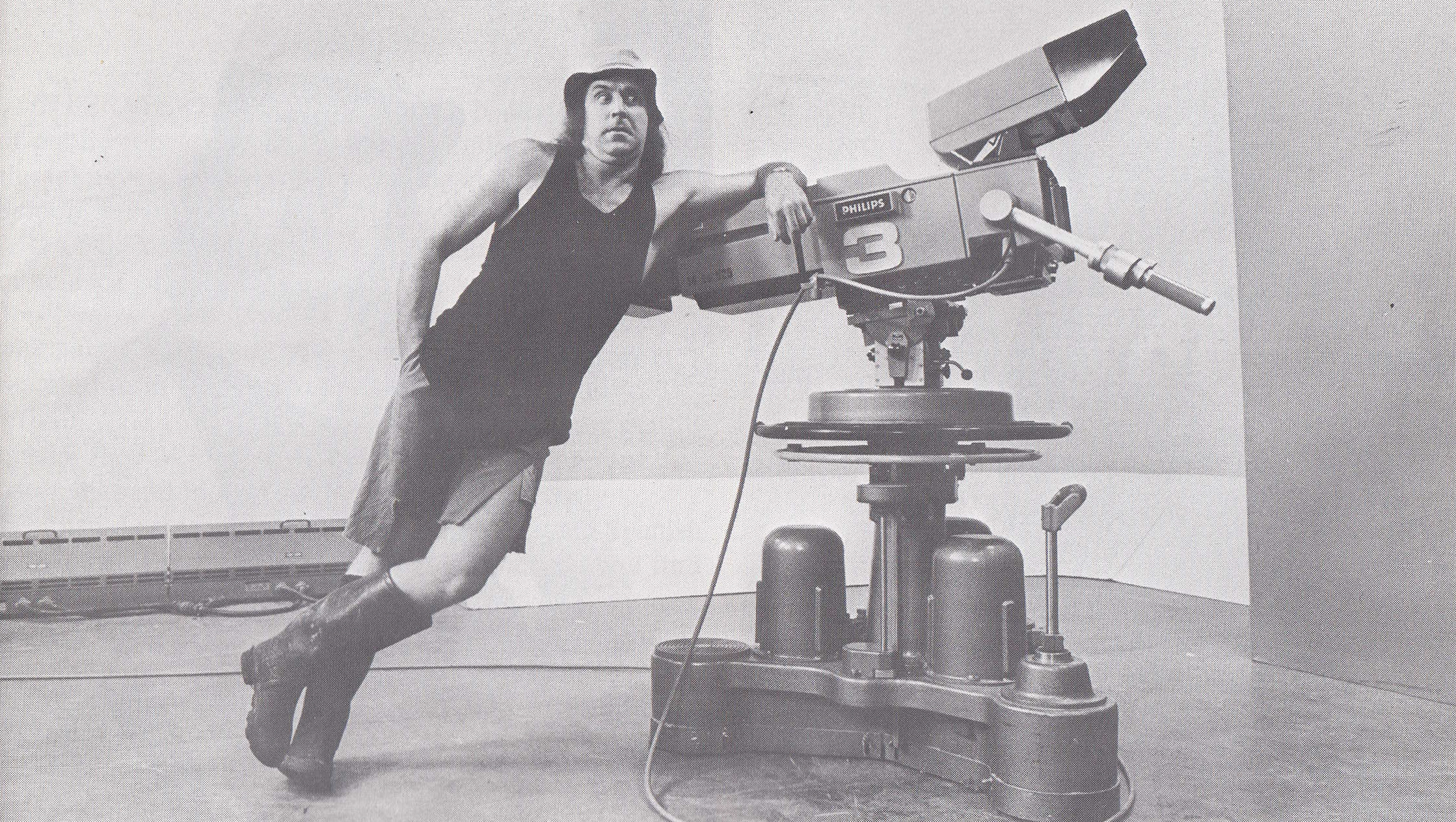

Publicity shot of Fred Dagg in 1975.

Lawyer Tim McBride on the Young John Clarke

I have photos taken with John (and others) from primary school, high school, and university. They always make me chuckle.

After distinguished service in World War Two, John’s father and my dad both moved to Palmerston North with their wives. It was there they had their children. John and I were born a few months apart. Our friendship began at College Street Primary School.

John was a popular boy with sparkly eyes and a broad, welcoming smile. He had a keen sense of mischief. Many teachers had an authoritarian approach to their role. Subverting their authority in subtle ways — with the assistance of Goon Show style humour on occasions — was the only safe way to avoid detection. One of our teachers was Mr Minty. With John’s encouragement, he quickly became 'Mr Minties', a popular sweet at the time. We cracked up every time his name was called.

In 1960, John’s family moved to Wellington. I followed two years later, to begin secondary school as a boarder at Scots College. I remember the sense of relief I felt, when I discovered John was a day boy. We rekindled our friendship. During those miserable three years as a boarder, John and his family were very kind to me. Their welcoming Wadestown home was one of my sanctuaries. At Victoria University, after two years back in Palmerston North, I discovered that John was a fellow law student. We rekindled our friendship yet again. John left the 'boring' legal world at the end of that year — and the rest is history. It took over 40 years before I had the courage to do so.

John had fond memories of growing up in Palmerston North. He maintained a keen interest in the lives of his old classmates. It was John who gave me the nickname, ‘Moth’— a play on my first name, Timothy. Whenever I have to complete documents requiring my full name, Timothy James McBride, I find myself remembering dear John. What a kind, gentle, ever-so-talented friend.

The Role of a Lifetime

By Lorin Clarke 22 Jun 2021

John Clarke, my dad, best known for a period in the 1970s as Fred Dagg, didn't become my dad until 1977. He became my sister’s dad four years after that, in 1981. My mum was involved, too, I am told. To us, his kids, his role as our dad was the starring role of his lifetime. We were always aware that he played other roles — both in Australia, where he lived with us, and in New Zealand, where he was born and raised.

After New Zealand, Fred Dagg popped up in Australia, delivering a series of lectures on ABC Radio and opining occasionally in the newspaper. If you looked out the window of our kitchen on a Saturday morning, chances were you’d see Fred mowing our front lawn, in the gumboots, black singlet and pair of shorts that looked like they’d been through a combine harvester. If he saw you watching, you sometimes even got a bit of the slapstick tomfoolery — tripping on an invisible fence wire, yelling incomprehensible instructions at our dog. Years later he donated the outfit to Te Papa. I believe he had it dry-cleaned first.

This thoughtfully curated collection, put together by NZ On Screen, shows us glimpses of John Clarke in the early days, before his children met him. We see him engaging in a conspiracy with John Banas in Buck House in the 1970s, including some Groucho Marx double takes and a defiant and slovenly physicality. You can see, in Country Calendar, how much he enjoys sitting with the Trevs around the breakfast table, delighting in the performances of these hilarious guys (including Banas) — a joy he describes in his interview with Ian Fraser.

Fred Dagg and the Trevs, in Country Calendar (1974).

It’s astonishing, in a way, to see how young he is in these early days (aged 25 to 28); to realise that Dad performed the Fred Dagg character in New Zealand for no more than four years in total. There’s footage of him dressed as Dagg, partaking in a Telethon. I watch this with my mum who smiles and says "I remember this night". But to me it’s pre-the-starring role-of-his-lifetime. I mostly study it for clues of the man I will come to meet a few years later. In one Telethon clip — a glorious time capsule of shambolic, early 1970s live TV, if ever there was one — he appears from offstage, rests his lit cigarette on the panel, and drops to the floor to do some press-ups to secure a donation.

It’s clips like these that offer clues to the broader cultural purpose of this collection. We witness not only a person finding their way as a performer and a writer, not only an artist migrating to another country and negotiating a relationship with a new audience, but also the television medium becoming more sophisticated — developing its own languages, rhythms and tones. The changes in technology alone are incredible, from those grainy black and white films of Fred Dagg standing in one spot and talking down the barrel of the camera, to the mockumentary style of The Games. As Dad says to Ian Fraser, The Games was shot as a documentary, written as a satire, and played as a drama. As it happens, it was also classified by the channel on which it aired (ABC TV) as a comedy. That’s another change. Back in the early days, television stations didn’t have enough shows on their books to justify a comedy department. In fact, as Fraser observes, when Fred Dagg first appeared on television there was only one TV station in the whole of New Zealand.

From book The Thoughts of Chairman Fred (1976, courtesy of Fourth Estate Books/Fourth Estate Group).

In that early footage of Fred Dagg you can see him learning how to think on his feet — and, as he would say, how to "act his way out of trouble". He learned how to film something by standing in front of a camera that he himself had plonked in the middle of a paddock; how to edit it later; and how to perform with all of this in mind. His joy is obvious — you can see him having a ball, making things up as he goes along, or nodding to the audience in the middle of a pause. In his interview with Ian Fraser, he reflects on the pitfalls of learning to be funny on the run. He is embarrassed, he says, about the times he went for the easy jokes and stumbled into crude stereotypes because they got a laugh.

There are interviews in this collection that take place when my sister and I are kids, when Dad is still new to Australia. In several of these, there’s footage of him writing. He writes to clarify what he wants to say. When writing, he becomes focused and careful. In later years, he isn’t tripping over fences, emptying water out of a gumboot or butting out a cigarette on live TV. Yet there is always an element of playfulness, of squinting into the sun in a singlet, of connection with the audience he found in New Zealand. Some things never change.

- Melbourne-based Lorin Clarke writes for television, radio, podcasts, and other places besides. Her website can be found here.

The Rise of Fred Dagg

By Paul Horan 22 Jun 2021

This collection is the most complete review of John Clarke’s New Zealand screen work to date. Born in Palmerston North in 1948, Clarke spent most of his career across the ditch, where he is still considered one of the most influential figures in Australian comedy. From The Games to Clarke & Dawe to Death In Brunswick, he helped form Oz screen culture, and his work as a poet and author is yet to be matched. But he was always happy to be claimed as a New Zealander.

During 2018 and 19 I did over 100 interviews for the documentary series Funny As, many of which have a home here at NZ On Screen. John Clarke was by far the most talked about person — as an influence, as a friend, and as the founding father of modern New Zealand comedy. His friends from varsity days — Roger Hall, Simon Morris, Dave Smith, and Helene Wong — remember his first performances as being something totally new.

Helene Wong, one of the people interviewed by Paul Horan for Funny As: The Story of NZ Comedy (2019).

Clarke's friend Ginette McDonald gives insight into how he started out as a professional. Then there are the fans like Oscar Kightley, Jeremy Corbett and Jesse Griffin who recall seeing him on TV, buying his record, and getting an inkling that comedy could be the thing for them. It really is hard to underestimate his influence.

This collection takes in all of his local work, especially the extraordinary period in the mid-1970s, the formative phase in Clarke’s career. He got back home from his OE in the United Kingdom in 1973, and four years later left permanently for Australia. In that short period of time he launched Fred Dagg (still our biggest comedy icon), released an album that was the top selling Kiwi record until quite recently, and undertook the biggest live tour a comedian had ever attempted. Comedy in New Zealand has never been the same.

Initially, John Clarke rose to fame on New Zealand television by playing Dagg in short comedy pieces, which appeared on news programmes. In these two minute sketches you see a young man in his 20s developing his own TV style, and learning on camera.

There was no TV school to attend in the 1970s, so most people learnt their trade by getting a cadetship with the NZ Broadcasting Corporation. Clarke had worked there as an assessor before going on his OE. Seemingly the biggest perk of this job was that he could watch reels of comedy again and again. This is how many comedians later learnt their trade — but in the pre-VHS era it was almost impossible. In particular he watched anything he could find featuring British comedy legend Peter Cook, including 1964 TV special of Beyond the Fringe. This was how Clarke figured out how TV worked.

Fred Dagg makes his TV debut on Gallery, in late 1973.

The vast majority of short Fred Dagg sketches appeared over just three years, from 1973 to 1976. As Clarke’s later career shows, it was the small segments that he came to favour when he created the Clarke & Dawe segments — still considered the most important satire series in Australian TV history. The Dagg pieces were well thought out, but not really written scripts. This allowed for improvisation, but also meant he occasionally forgot what to say; this is where his asides to whistle at the dog or tell them to "get out of it" came from. Clarke was paid just "20 to 30 bucks each" for his work, and counted himself lucky that his wife Helen had a teaching job at the time.

But it was the Country Calendar Christmas special in 1974 that really made Clarke a household name. It was like nothing anyone had seen before. Suddenly everyone seemed to be doing a Fred Dagg impression.

As an aside, many great moments of TV history have been lost or erased. One of the reasons this collection is so complete is not because the Dagg material is so famous; the material is preserved because Clarke always knew the value of it. There are still some titles missing, like an entire series called Lectures on Leisure, that he came back to New Zealand to film in 1978. We are still on the hunt.

The creation of this collection partly came out of the making of the Funny As series (which I produced with Cass Avery). Mark Hutchings, then at TVNZ, did most of the detective work tracking down Fred Dagg clips for the series, in consultation with John's wife Helen McDonald and their daughter Lorin Clarke. This helped open some doors for NZ On Screen.

In the end, regardless of what historical or cultural importance you attach to them, these clips show Clarke doing what he was put on this green earth to do: making the audience laugh. After 50 years you can still see the joy of how these were created.

- Paul Horan co-founded the NZ Comedy Festival and Auckland's Classic Comedy Bar. His television credits include The Topp Twins, Super City, comedy history series Funny As and Australia's Rove Live.

A Beloved Extra Brother

By Ginette McDonald 22 Jun 2021

Ginette McDonald gave this speech as part of John Clarke's Memorial Celebration at the Melbourne Town Hall, on 2 July 2017.

Good evening. My name is Ginette McDonald and I'm here from New Zealand to represent the McDonald family— no relation to Helen [John's wife Helen McDonald], worse luck. John Morrison Clarke, Nobbie to his Kiwi friends, rocked up in our kitchen at the age of about 18, and instantly and forever became my brother Michael's dearest friend, and an extra brother to us all. Nobbie always said my mother was the first adult to encourage him. She said, "Gosh, Nobbie you're priceless! You know you've really got something". What were we, chopped liver?

Anyway, the boys met on their first day at uni, and together with Rob Goldblatt and Simon Morris, formed a tight fraternal bond, unbroken by 50 turbulent years. And Sam Neill was there too, somewhere in the mix, but he was the sort of shy earnest boy, in a duffle coat and desert boots — with no hint of the cinematic heartthrob and urbane silverfox he was to become. But those other four were young tigers, who wanted to roar — mostly with laughter at each other's jokes — which were pastiches of Peter Cook, PG Whitehouse and filthy doggerel Shakespeare: terribly filthy, but gloriously innocent at the same time.

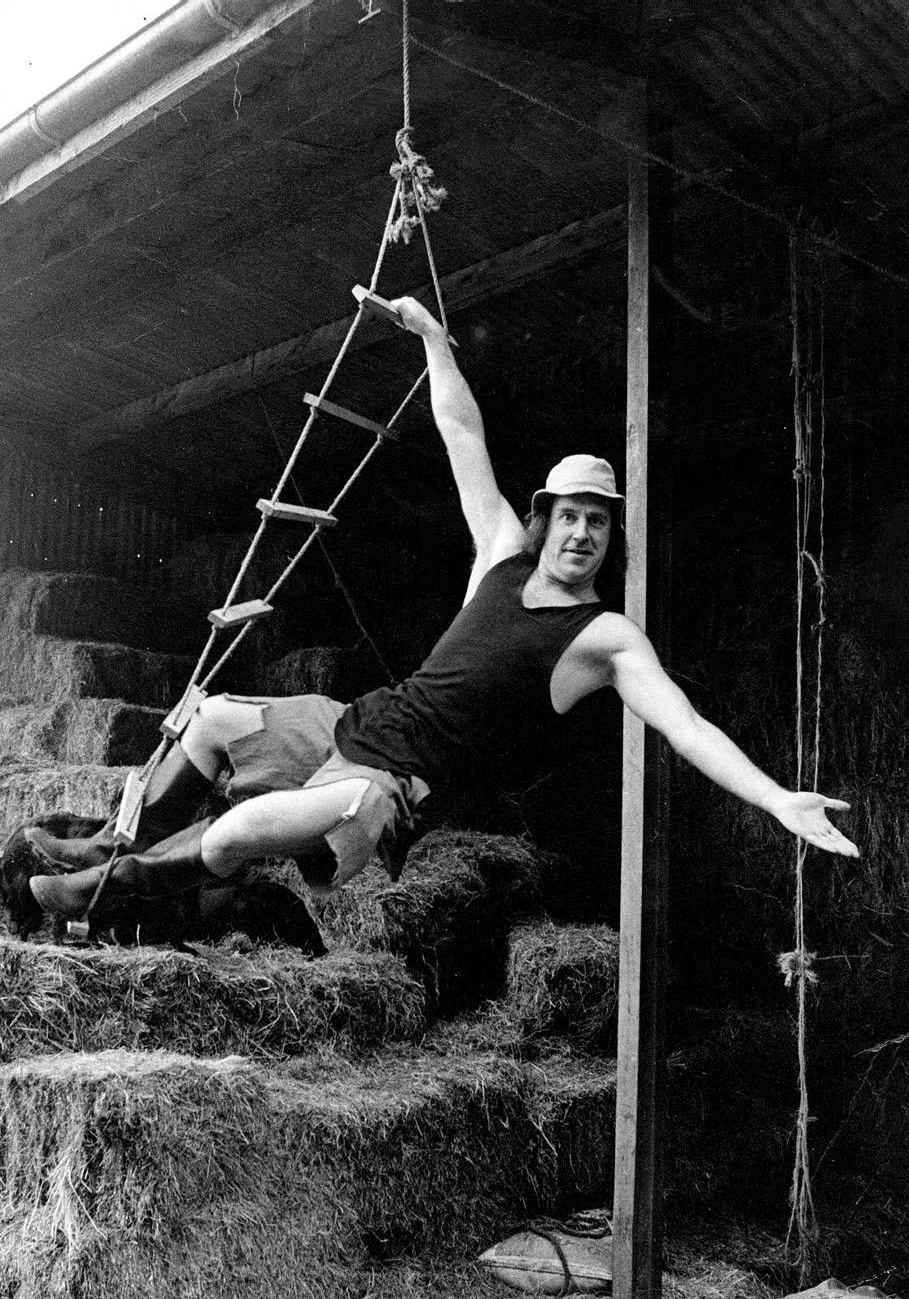

Not a great deal of scholastic work got achieved at uni, it's fair to say. They did go to lectures, but were more keen on performing in the Victoria University revues, where John's larrikin, laconic take on things first started to be noticed. Then for nearly two years, John and I performed with two others — one of whom was John Banas — in a late night revue called, appropriately enough, Knackers, at Downstage Theatre in Wellington.

We were a hit — queues to get in — mainly to see John. He was original and hilarious, and extremely relaxed on stage, quite possibly due to the herculean amount of bevvies he'd consume at university parties before the show. But you know, I always thought that John Clarke only ever drank in those days to make other people seem more interesting. That show was a bit of a turning point for John: the moment where he realised he was onto something; an ability to entertain, win people over, and possibly get paid for having fun — fun being the main objective.

In 1971, Nobbie and Michael headed for London and soon blagged their way into a posh garden flat in South Kensington, occupied by a demure English debutante, Charlotte. It was an eye-opening time for Charlotte, as the flat rapidly became party central for various itinerant Kiwis and Aussie dentists. I was a frequent visitor, flatting as I was down the road with John's beloved only sister Anna; incidentally, every bit as clever and every bit as quietly subversive as her big bro. I auditioned for Bruce Beresford for the Barry McKenzie film [The Adventures of Barry McKenzie] being shot in London. He said "I don't want you. I want an Australian man". I said "don't we all". But I told Nobbie; I sent him along and he got a part. No fee, paid in jugs of beer. But Nobbie said he didn't care. He would crawl over burning coals to meet his idol Barry Humphries, and now they were friends. That's what you call a score.

From 1976 book The Thoughts of Chairman Fred. Photo by John Selkirk, courtesy of Fourth Estate Books/ Fourth Estate Group.

Michael took himself off to a crash course in Italian at Perugia University, and returned to London with two new Aussie friends: a petite, clever girl called Helen and her mate Pierrette. They soon became a fixture at the rowdy parties. But conversations between Helen and John were minimal to say the least. John's default position being watching the Wimbledon tennis from the depths of the sofa. Helen would arrive and say "Gidday John", and John would say "Gidday Helen". And that would seem to be that.

Until, after a night of spectacular carousing, many of us stayed over. In the morning my brother Michael and I arrived in the sitting room at the same time to see John and Helen, fully clad, fast asleep, snuggled up together in a single sleeping bag — looking like a couple of contented bush babies. Well, you could have knocked us over with a prestressed concrete beam. That would have to be the most subtle and the most laconic courtship in history. I mean, John was interested in girls of course, but he wasn't a player. He was also at heart a gentleman. Helen has, of course, always been her own woman, very much in her skin, very independent. But they each saw something in each other, a chance to build the kind of life that many crave, but don't always find: the life where two people walk side by side down the same road, looking outwards, not inwards — but usually looking in the same direction.

They took off for Australia, then New Zealand, got married. John stayed long enough in New Zealand to invent his lovable Kiwi icon, the irreverent farming identity Fred Dagg, and stir up some dust among the rather repressive state television executives —otherwise known as Programme Prevention Officers. And then they sensibly buggered off to Australia, where they really appreciated him and his singular talent, and where he and Helen produced their two beautiful, spirited daughters, Lorin and Lucia.

John and his sister Anna didn't have the easiest of upbringings, and like many very clever people, were very sensitive. But they both obdurately refused to let their parents' battles define them, choosing instead to seek the amusement factor in the most grim of situations. And that is the birthplace of satire: good comedy always teeters on the edge of pathos. In the movie Sliding Doors, the character has to decide which door to take: one leading to a contented life; the other, not so much. We're shown both. But when John Clarke chose Helen McDonald, it was his sliding doors moment. He did not fall prey to some predatory high maintenance nightmare of a woman. But he ended up with the girl who could have had anybody, but instead, she took our darling Nobbie by the hand and led him gently away to a more ordered existence. She had her own distinguished academic career, but she gave him the space and security of her love to become the very best version of himself. And he in turn, rose up and up and up.

And our family bonds remain. My Melbourne-based sister Nicky and her husband Gary spent tonnes of family time with John and Helen. Christmas lunch was something of a challenge when they were in that tedious vegetarian phase. I mean no disrespect to vegetarians. My sister Nicky and Helen have a secret gym they go to, to keep their figures. You can see I haven't joined them. And my brother Michael and John Skyped, at least twice a week, still spouting Shakespeare, still gurgling with laughter at each other. Michael's computer now says 'John Clarke is offline'.

At a certain time of life, one becomes rather inured to the inevitable death of friends. We ring each other up, we try to make light of our loss: "Oh my God, they're dropping like flies". But Nobbie going was a shock. Through all the years, through all the incarnations — public and private — he was always there: my beloved extra brother John Clarke, kind and curious, scornful only of bullshit and deceit, seemingly invincible. We thought he'd go last, honestly we did. Instead, while taken far too soon, his death was as he had lived, walking down the same path with the love of his life; her sun to his moon, both looking outwards, but in the same direction. As his character Fred Dagg might say, "all in all, not a bad innings".

- Like John Clarke, Ginette McDonald is often associated with a comic character from early in her career: Lynn of Tawa. McDonald has also produced and directed TV drama, and won awards for her acting.

"We Need Some Women Writers!"

By Wendy Harmer 22 Jun 2021

"We need some women writers!" Something you’d expect to hear from the producers of a TV sketch comedy show now…but in 1984? Almost 40 years ago? Not bloody likely!

John Clarke bought his own trowel and helped cement the success of women in Australian comedy. Not only did he seek out women to contribute to comedy writing teams he knew of, he also wrote great characters for women in his TV and film projects.

John was a genuine fan of the comic female voice.

So many of my Aussie sorority can relate a private message of support and encouragement when she took on a daring project of her own — phone calls, emails or a personal encounter in which John praised our work, and dared us to keep going. He loved us for our clever, subversive, determined, silly selves when we were so often overlooked in the male-dominated arena of comedy.

John was never one to grandstand or take credit, but often we’d find out that he’d sought to amplify our voices with his behind-the-scenes support.

A hallmark of John’s comedy style was to quietly chip away at the foundations of seemingly solid edifices until they tilted to the absurd. The mantra that "women aren’t funny" was just one of many flimsy constructions he gleefully dismantled.

The roll call of women he championed makes for a who’s who of late 20th century women in comedy. As a younger man, he 'got' the work of Margaret Dumont in old Marx Brothers films, and the recordings of comic monologist Ruth Draper, who died in the 1950s. In the 1980s, he championed the cartooning of Australians Jenny Coopes and Kaz Cooke. He wanted to work with newbies like me and Tracy Harvey, and told everyone to watch Mary Kenneally, Marg Downey, and Kath & Kim's Gina Riley and Jane Turner, among others.

He regarded us as colleagues, equal to men in making him laugh.

_____________________________________________

My own comedy career may not have ever happened without John. True story: in the early 1980s I was performing in a sketch show at Melbourne’s legendary Last Laugh theatre restaurant.

Sunburn the Day After was a four person revue of stand-up, send-up and song, dedicated to the rituals of the Great Aussie Summer — the crowded caravan parks, the "icy can of Coke" giveaways on commercial radio, the punks sweating it out at inner suburban swimming pools. Plus a bit of current political satire chucked in for good measure. You get the picture.

And it was a smash! Full to the rafters. Sold out for weeks. One night after the show I was approached by someone I’d never met, who asked: "Who wrote this show?"

I remember that question because I couldn’t recall anyone asking it before. I said that I’d written most of the sketches, and that seemed to be the end of the conversation. A week later, a call came from ABC TV producer Ted Robinson, who was working on a pilot for an unnamed TV show. "John Clarke says we need women writers. He told me to come along and see your revue. I loved it. Can you come to a writers’ workshop?"

From a community hall in Elwood, St Kilda, to being cast (along with Tracy Harvey) on legendary hit ABC political satire show The Gillies Report, in just a few weeks.

The cast and crew of The Gillies Report; Wendy Harmer is seated at far left. John Clarke is seated at far right.

And from there, on to being the host of ABC TV’s live comedy and music show The Big Gig in 1989 — the first woman in such a role. John was, again, in my corner — as he was for all my comedy career. I think back on all this now, and still remember the thrill of recognition for being a comedy writer!

"We need some women writers!" It may not sound revolutionary now…but almost 40 years ago, it was. Think about how far we’ve come.

Thank you, John.

- Wendy Harmer is an Australian journalist, stand-up comic, TV host, broadcaster and author.

Bryan Dawe on Life without John Clarke

By Anthony Ham 22 Jun 2021

This article was originally published in October 2020 in Australian magazine The Monthly. Reprinted with permission.

When we lost John Clarke on 9 April, 2017, Bryan Dawe also disappeared from our TV screens. For three decades he had been a fixture, part of the most enduring comic double act in modern Australian history.

In a year when reasons for laughter have been in pretty short supply, Clarke and Dawe’s mix of biting satire, impeccable timing and onscreen chemistry have been sorely missed. One can only imagine what they might have said about the prime minister’s trip to Hawaii while the country burned, and about politicians of all stripes posturing over the Ruby Princess, hotel quarantine and the aged-care system.

John Clarke and Bryan Dawe - © Photo by Krista McClelland. Supplied by Bryan Dawe

Dawe feels the absence, too. "It does feel as if we have stopped laughing because everything is so damned overwhelming. We’re all just bogged down in so much noise. We go back into our hole. We don’t have a lot of time to find the irony."

Without Clarke and Dawe, it is easy to imagine that these bigger issues are too serious for comedy, that the role of the comedian is to offer escape instead of engagement. Dawe disagrees. "Comedy is easy to do now because it’s light – they let you off the hook. If you’re going to do satire, you’ve got to do your homework. And it’s got to hurt somewhere. It shouldn’t be personal. But it’s got to hurt. Some people do satire, but they’re attacking the victim, not the perpetrator."

But Dawe doubts whether he and Clarke could even find a place in the current media environment — whether there is a space left for comedians to call politicians to account for their hubris. "The problem you’ve got now is that the ABC is offering up its own self-censorship in a brilliant way. People don’t have to be told they can’t touch that subject. They just know what’s going to happen if they do."

Back when Clarke and Dawe were on our screens, which is not really so long ago, things were different. With a platform free from interference, the two old friends were, like Monty Python in its heyday, having great fun making serious comedy. And, over time, it became second nature. Which is why, of course, Clarke and Dawe worked.

"We did have a lot of fun. It got to the point where I could just pick up a script and I’d know where the beats were. [Clarke] would observe my tone as I picked it up and observe how I dealt with it. He didn’t direct me as to how he thought this thing should go. He just let me read it, and he’d trust me. There was never a discussion."

© Photo by Shelley Farthing-Dawe. Supplied by Bryan Dawe

At the heart of it all lay a very special friendship, to the extent that you can imagine Clarke and Dawe continuing even after the cameras were turned off. "If yakking had been an Olympic sport, John would have won gold for two countries," Dawe says. "We both loved talking. He had the depth of understanding about history. John was interested in people because he wanted their view of the world. That’s why he was so damned good. That’s a rare thing. That’s what I miss. I’d bring stuff to the table he didn’t know about, and he’d do the same."

For Dawe, Clarke’s death was intensely personal. "Apart from my parents dying, that was the most painful part of my life. I lost more than just John and the work. The work was easy. It was all the other stuff with John that was really, really important. I respected his opinion about the world more than anyone else … when my wife at the time and I talked about having a second child, I was so unsure. So I rang John one night — it was very early on, when we just started working together — and I put it to him. I maintain that if I recorded that conversation, his answer, and replayed it on radio, there would have been a baby boom that year. He made it sound like it was the most wonderful thing. Our son turned up out of that conversation. When you lose something like that, you lose —"

Unusually, Dawe finds himself lost for words.

There was also a professional grief, and Dawe knew immediately that there was no substitute for Clarke. "When you’ve worked with the best…" His voice trails off. "People have approached me. I just didn’t answer. There’s no way. We had nearly 30 years together. It’s there. It’s on the record. It’s a bit like when you do the remake of a movie – it doesn’t work. It never works."

Many Australians felt the loss almost as personally: as Dawe mourned, so too did the nation. For a time after Clarke died, Dawe carried the burden of his own grief and of becoming the focal point of a profound national grief — one that took many commentators by surprise.

Photo supplied by Bryan Dawe

"I couldn’t go out of my house. There was not one day where I didn’t have someone talk about us. I had to stop working. I couldn’t cope."

Dawe fled to Tangier, in Morocco. It was there, where no one knew Clarke, that Dawe was able to heal. "Tangier is about reinvention," says Dawe. "I didn’t set out to do that, but it just gave me that breathing space. I hadn’t reflected on John’s death six months after he died, because I didn’t have time, didn’t have the space to do it. In Tangier I was able to switch off while I was there." Dawe was born in Port Adelaide and is still drawn to the intrigue of port cities. "That’s why I love Tangier. And I love port towns because they’re so used to people coming and going. They’re far less judgemental. They ask no questions."

While he was in Tangier, Dawe threw himself into local life, befriending barbers and shoe shiners, passing days in the Gran Cafe de Paris, the famed haunt of spies and intellectuals for more than a century. "Casablanca, the film, is really about Tangier," says Dawe. He also immersed himself in creating the multimedia or digital artworks that are now his passion.

Dawe had always been something of a renaissance man, a restless creative unbound by genres or artistic norms and a man of voracious appetites. In addition to comedy and politics, he has made important contributions to the world of music, public speaking, photography and, now, the visual arts. In Tangier, through his art, he also found healing and solace.

"The art gave me a release from having to think about losing John. That’s the big one. I’d already had an exhibition in Tangier a year and a half before. I just focused on the art and came back with three exhibitions."

© Photo by Krista McClelland. Supplied by Bryan Dawe

He knew that he had to return and face an Australia without Clarke, but time had brought if not a measure of healing then of space. "It was only when I got off the plane coming back, and I literally didn’t get out of the airport before I said, 'Oh my God!' And then I had to learn how to deal with that."

Dawe now enjoys being out of the limelight, although he maintains the right to occasionally stick his head above the parapet. "Most of the time, I don’t bother commenting, because you just get the moronic brigade writing crap. I don’t engage. But every now and then something annoys me, and I just throw it out there and go away."

Most recently he has maintained a busy schedule of digital art exhibitions, with plans for an online exhibition before the end of the year (at bryandawe.com). In the process of creating art, Dawe remains the same man who sat across from John Clarke for three decades, having a ball, trying not to laugh. "I love it. It’s a bit like writing — you hate it and you love it all at the same time. It’s the means of staying alive in the water. I can sit here in the dark, in the middle of winter, and just start playing."

Raconteur. Provocateur. Commentator on the state of our nation. Bryan Dawe is not done yet.

Anthony Ham is an Australian nature and travel writer, who's written 100+ Lonely Planet guides and appeared in media in Australia and abroad. His first book was The Last Lions of Africa (2020). He lives in Melbourne.