The Bruno Lawrence Collection

The Bruno Lawrence Collection

This collection has three backgrounds:

"He was the Last Man Alive"

An Enduring Symbol of NZ Cinema

Numero Bruno - Director's Notes

"He was the Last Man Alive"

By Barney McDonald 04 Feb 2011

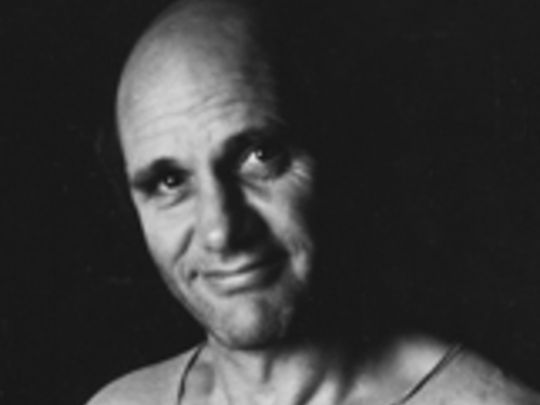

Bruno Lawrence is the only New Zealand actor who consistently unsettles me. I say 'unsettles' in the present tense. Although David, as he was christened in England in 1941, died in 1995, his innumerable screen roles continue to haunt my psyche over a decade later.

Entering my teen years at the start of the 1980s, it was impossible to avoid Lawrence. He was in all the Kiwi films of my youth, from Beyond Reasonable Doubt in 1980, to Smash Palace and Goodbye Pork Pie in 1981, Utu in 1983, then The Quiet Earth in 1985. He was everywhere, even including a stint on New Zealand TV’s first soap, Close To Home, in 1975, when I was still knee high to a wētā.

But that’s not why he continues to be unsettling. What resonates through the ages — and it does feel like Lawrence has been with us, in life and death, for a very long time — is his brooding intensity. There’s something undeniably intimidating about Lawrence, the screen legend. Perhaps it also underscores how intimidating he could be as a drunk too, as recounted by his many friends and colleagues in Steve La Hood’s outstanding biographical documentary, Numero Bruno.

Lawrence was the real deal: a man who could emote and decimate in equal measure, sometimes in the same moment.

As an army brat, I was shunted around the country quite a bit growing up. I met many men like Lawrence’s plethora of iconic screen characters. These were hard men with glimmers of humanity. They could charm the pants off the ladies and have the kids giggling with glee in an instant. But they could also break hearts, bones and promises. They did what they liked, whether we liked it or not.

Although it seems impossible now to find the exact source of the quote, there’s a comment attributed to Jack Nicholson (another actor honoured with first name recognition) in the 1980s, along the lines that Lawrence was one of his favourite actors and the only actor who scared him. Possibly embellished by folklore, Jack's nod to Bruno sums up the power the unremittingly Kiwi actor possessed.

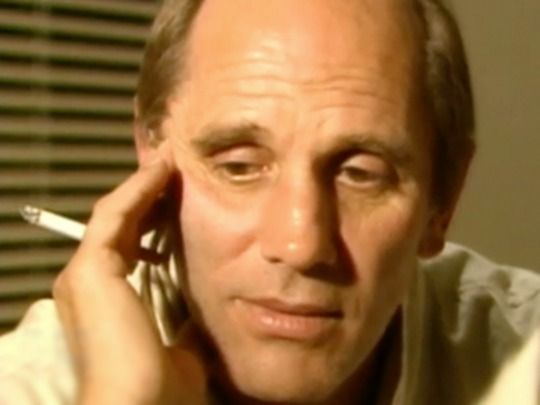

Witness Lawrence’s searing performance in Roger Donaldson’s Smash Palace, a film the actor had a hand in scripting, and you see a good keen Kiwi bloke in the throes of collapse. Encapsulating the colonial contradictions of antipodean life, Al Shaw (Lawrence) is a racing driver turned mechanic whose marriage is in tatters. Back against the wall, he kidnaps his daughter (wonderfully played by nine-year-old Greer Robson), and becomes a rebel with a cause. It’s arguably Lawrence’s grittiest performance and a precursor to subsequent Kiwi outsiders like Jake the Muss in Once Were Warriors and David Gray in Out Of The Blue. However, Lawrence maintained audience sympathy throughout, something he was unusually adept at.

Of course, Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth was Lawrence’s finest hour-and-a-half, largely because he occupied the screen in almost every scene, spending at least the first half-hour on his own, shooting shotguns, cavorting in petticoats and running over prams with heavy machinery.

It’s a strange film that thematically feels very current, even though the production values and special effects are somewhat dated. Lawrence's character winds up playing second fiddle to Pete Smith’s Api, but he seems to be having a field day. Despite the character’s flaws it’s a role that showed Lawrence could also be a thinker, something often overlooked when analysing his work.

In his element, Lawrence could play comedy with a wry sense of playfulness, or menacing violence without any hint of irony. In the frankly bizarre Venus Touch episode of 1982 TV series Loose Enz, Lawrence plays an eccentric patient of a sexologist, who believes he has the magic touch with women. Ernest (who lives up to his name) was surely a sly nod to his rough diamond off-screen reputation.

The character is an odd anomaly in the actor’s career, which manages to reveal much about the man and his methods. At a time when Lawrence’s film career was ticking over nicely, he’d happily take a role in a smartly-scripted sex farce (newsreader Angela D'Audney goes full frontal) simply for the fun of it. Furthermore, when it came time to crack Hollywood, as subsequent Kiwi actors have, Lawrence wasn’t particularly interested.

Even playing a dangerous guy, Lawrence could be hilarious. In Goodbye Pork Pie, which still has the best car stunts in this country’s movie history (albeit in an old Mini), his character, Mulvaney (aka 'Baldini'), is a petty drug dealer and chop shop crim.

Wearing a heavy leather hat, Lawrence is portrayed as menacing in director Geoff Murphy’s establishing shot. Those intense eyes, shielded by the brim, would make a gang member wither, until that familiar sparkle of humour lights up the character and the scene. It shows his duality — a Jekyll and Hyde quality that made him such a compelling figure across 20+ feature films and numerous TV roles. Those eyes, which everyone in La Hood’s documentary has a different take on, continue to radiate beyond the grave.

"I get the feeling we’re dead or in a different universe."

- Barney McDonald edited and co-founded popular youth magazine Pavement. Since its last issue in 2006, McDonald has contributed to The NZ Herald and The Sunday Star-Times.

An Enduring Symbol of NZ Cinema

By Keith Aberdein 04 Feb 2011

In 1996 the Sydney Film Festival honoured Bruno Lawrence posthumously with a tribute night. New Zealand writer Keith Aberdein spoke about Bruno, before a screening of Smash Palace. Thanks to Keith Aberdein for permission to republish his words here.

Among the many adventures that made up the life of Bruno Lawrence, he once stowed away on the liner Canberra as it sailed from New Zealand to Sydney. As he explained to the magistrate: he was just having too much of a good time to get off.

Last year it took three major cancers to stop him having a good time and make him get off this particular ride. So even though we saw him buried in a Māori cemetery only a golf slice from the Pacific coast of New Zealand’s Hawke's Bay, don’t be entirely surprised if he rolls up here — late — and wonders "what’s all this crap about?"

An actor, Marlon Brando is alleged to have said, is a guy who if you ain’t talking about him — he ain’t listening. On that basis, Bruno was no actor. He was, in fact, sometimes accused — always by other, less successful members of the profession — of not acting. Of merely playing himself. They should’ve been so lucky — or so good.

As a friend for more than 30 years, I have formed a simple prejudice about Bruno: without him I doubt that there would be that rather vague thing we call the New Zealand film industry.

I know in an era when the director has become bigger than god it's heresy to suggest that a mere actor sustained any country’s cinema. But then why is it that in both Australia and New Zealand we have produced many more directors than lead actors?

In the last 25 years of New Zealand film there have been maybe only three leading men. And by that I mean performers who can hold a picture together — even a bad picture — who can drag people away from television, and whose name gets the thing up and financed.

First there was Sam Neill. But Sam made just one theatrical feature before he left in the 70s to seek his brilliant career, and his only other New Zealand appearance [up to 1996] was in The Piano.

If Temuera Morrison can kick on from Once Were Warriors, he may be better than any of them. But the fact is that between Sam and Tem — essentially the entire 1980s — there was only Bruno. And that’s not to dismiss John Bach, or Zac Wallace, Kelly Johnson or Martyn Sanderson.

And maybe to understand what I’m on about in terms of Bruno’s place in the scheme of things, we need to remember how the modern New Zealand film industry began and then hung on. For one thing, you’d have to be crazy to believe that you could make cinema features in a country of only three million people — especially when a big proportion of these people wanted Piggy Muldoon to be their Prime Minister.

Unlike Australia in the 70s, we didn’t have [Prime Ministers] John Gorton or Gough [Whitlam] or [producer] Phillip Adams. We didn’t have enough actors, directors, technicians or writers to fill even a Pacific Drive crowd scene.

The creation of a New Zealand Film Commission with government support was a kind of conjuring trick. Among the stunts we pulled was to invite an Australian director to screen his new movie one Saturday morning, to a Wellington audience that included a very junior cabinet minister from a very marginal electorate. We duly applauded loud and long. The Aussie director monstered the politician about the need for his government — as a matter of national pride — not to allow Australia to have something that New Zealand didn’t.

I know he’ll forgive me for saying we were just a little surprised when our junior cabinet minister subsequently got us a film commission and some money. It wasn’t so much that the Aussie director, this great unsung hero of the New Zealand film industry, was Bert Deling, but that the film was about drugs — Pure Shit (it even had to be retitled Pure S. for New Zealand audiences).

Of course films had been made without a commission and tax concessions. Nobody much went to see them, and overseas interest was restricted to the Tashkent Film Festival. But besides Bruno and Bert, there was one other hero in this story — Bruno’s then brother-in-law Geoff Murphy.

Through the 70s Murphy made a number of short films. He’d remortgage his house. He built his own camera crane and sound editing equipment. His first feature, Wild Man, in which Bruno was one of the leads, was shot largely on short ends and on film stock — not to put too fine a point on it — stolen from television.

Murphy didn’t only make his own films, he helped anybody who asked. Whether he now acknowledges it or not, Vincent Ward may never have finished his first film drama without Murphy’s assistance.

Goodbye Pork Pie, Utu and The Quiet Earth were all Bruno and Murphy collaborations, and along with Smash Palace they gave New Zealand cinema an international profile in the early 80s. This, in turn created a continuity for the next generation of Jane Campion, Peter Jackson and Lee Tamahori, and therefore an environment where locally-made films had become part of the scenery.

However, the industry in New Zealand after the first careless rupture was a very fragile thing. Like Australia, we were often making movies in which the most creative element was the tax write-off that the real estate salesmen investors were claiming. Kiwis also used to have a great belief in everybody getting a go; that giving somebody else a turn was only fair.

At any moment the whole thing could have fallen in a heap.

That it didn’t, I argue, has quite a lot to do with Bruno. Again and again he’d turn up and be the best thing in a whole lot of movies that fell into the category invented by a famous New Zealand grip when he said of one local effort — “I’ve seen better film on Geoff Murphy’s teeth”.

Bruno as a kind of laidback, postmodern institution, gave the industry a substance, a confidence factor for both the funding body and the filmgoer.

However flippantly he’d made the statement, the fact that Jack Nicholson had once said Bruno Lawrence was his favourite actor reflects perfectly Bruno’s importance. He is the one enduring symbol of New Zealand cinema through the 80s.

Smash Palace was the first real international breakthrough for Kiwi film. Pauline Kael hailed it, The New York Times included it in its best 10 films for 1981 and Bruno won Best Actor at the first Manila Film Festival, beating Jeremy Irons. It didn’t matter that the trophy he won looked like it had been designed personally by Imelda Marcos.

The New Zealand Film Commission had received an early assessment of the Smash Palace screenplay which said that the project sucked and the film should never be made. I happen to know this because I wrote the assessment. The fact that Roger Donaldson got his own back by casting me — a non-actor — in the thing suggests that directors' egos were smaller and less fragile 16 years ago.

Donaldson, a boy from Ballarat, had gone to New Zealand so he didn’t have to go to Vietnam. He’d made Sleeping Dogs with Sam Neill. At Cannes, Roger had shown we had a bit to learn about marketing when, in response to a couple of German buyers suggesting that Sleeping Dogs was too violent for them, snarled, "what do you mean? You bastards invented violence".

Smash Palace was his second feature. As co-writer (with Bruno and Peter Hansard) Roger was clearly working through — even self-justifying — the breakdown of his own first marriage. But as a shoot, while it wasn’t always comfortable, it was pretty relaxed. Two weeks in, the first assistant director walked off and we all just went on the shoot without one for a week. Most of the crew and cast lived in the caravan park and the local cop lent us his police land cruiser when our own wasn’t ready.

The script got substantially rewritten on slightly drunken nights before shooting, and at the end of the day Roger had to lie about how much it cost — inflating the figures — because American distributors wouldn’t look at a film that cost under a million dollars.

It was the film that springboarded Roger towards a career in Hollywood.

After remaking Mutiny On The Bounty, he went on to No Way Out, Cocktail, Cadillac Man, White Sands and Species. Roger — like Geoff Murphy, who now makes movies with the likes of Kiefer Sutherland, Lou Diamond Phillips and Steven bloody Seagal — is rich and semi-famous.

They don’t have to steal film stock anymore. But perhaps they should have taken Bruno with them, because it's possible — and just a little scary — that the film we’re now about to see is still the best film Roger’s made. But that's enough of me...So here’s the man himself...in Bruno Lawrence’s Smash Palace...Thanks.

- Keith Aberdein began as a journalist, and has written for a run of screen dramas including Pukemanu, Utu and The Governor. He also acted sporadically alongside his longtime friend Bruno Lawrence.

Numero Bruno - Director's Notes

By Steve La Hood 04 Feb 2011

Okay, I’m the bastard who wrote and directed the Bruno doco! It was more than 11 years ago and — still, parts of the family (Veronica most of all) have me high on their shitlist.

I still don’t know quite why, or honestly, what they could find to dislike about the film. I watched it again recently. Really, it’s a tribute to the man, the artist, the naughty, needy boy, the bloody genius.

I never really knew Bruno. I mean, I’d directed him, acted with him in a stupid skit comedy on TV, met him once in Three Lamps in Auckland and we kind of accidentally spent an afternoon drinking and smoking (both kinds) in the Tavern while this band he was ignoring (his band) was doing sound checks. But I never really knew him.

He was older of course — just that bit older and therefore cooler, and part of the famous rat pack of New Zealand music and cinema. I was just impressed that he knew my name and welcomed me like an old friend. When he died and a few years passed, and Nicola Saker said she wanted to produce a documentary on Bruno Lawrence, I thought it was a chance to repay him for the neat afternoon we’d spent — in the hot Auckland sun — out the back of the bar — talking all kinds of crap and laughing a lot.

If you look at the raw footage — from the dozens of interviews (including the ones we didn’t use at all) — you could have made a very different film about Bruno. It’s fair to say that while everyone’s eyes lit up as they told me what wonderful memories they had of him, everyone saw the other side too. There was always a subtext, always a "but you know..."

And, of course, I wanted to recapture that turmoil the man was able to create. I made repeated phone calls to Merata Mita in Hawaii at enormous cost, until finally Geoff Murphy gave in and spoke to me. He was grumpy, I was pleading (whining) — not a good look, and he said no, not even sorry, just no. Then I found the wild tapes of Neil Roberts' interview with Bruno in Sydney — where he talks about Geoff. And I HAD to use that.

And then all the others who’d loved his incorrigible wild antics — but also wanted him to grow older and a wee bit wiser with them — and expressed sorrow that he’d trapped himself in his reputation, like an insect in amber.

All of them — especially Veronica, who I admire for her forthrightness and sheer durability, but also the ones Veronica’s unhappy about — who equally loved Bruno: Keith Aberdein (I wasn’t supposed to talk to him apparently — "what would he know?"), and Andy Anderson (he was never Bruno’s friend apparently), and those who were approved — Wattie, John Charles, Tony Barry, Sam Neill, Rick Bryant, the Waimarama kids, even Greer Robson and Chris Seresin — all of them gave me their personal picture of Bruno. How can I be anything but grateful?

I’d never had any urge to direct a biography. Of anyone really. But Bruno’s story got to me. There’s so much of him in me — in all of us post-war, post-feminist, post-HIV boys.

Waka Attewell knew. We were doing joint interviews — from behind the camera and alongside it. Both of us pulling the stories out of people we knew — admired — feared — envied. A good director photography (and Waka is a VERY good DoP) always shoots what a director is thinking — not what he’s saying.

Geoff Conway and I kept writing the story we were editing on a whiteboard as we cut. We must have recut that film a dozen times. A good editor (Geoff is a VERY good editor) always cuts what a director is feeling — not what he’s saying.

Anyway, we all poured our hearts into this Bruno story. Me, Nicki, Waka, Chris and Jo Hiles and Geoff — for Bruno and for ourselves. Because that story was our story too.

And you know, TVNZ buried it in a January 2008 time slot — treated the film (and us) like shit stuck to their shoes — as they do — and, well, that was the last piece of television I ever made. Eleven years ago. I’m proud of Numero Bruno. It’s me at my passionate, loquacious best as a documentary maker. I’m really sad about the lacklustre industry that television in New Zealand has become, but then again — I don’t do that stuff any more, so I can say so.

Love, peace and creative fulfillingness to you all…

- Steve La Hood spent the first half of his career as a producer and director, directing episodes of Close to Home and Shortland Street. In 2000 he directed acclaimed documentary Numero Bruno. La Hood went on to craft museum exhibitions and visitor experiences with company Story Inc.