Gallery - Fred Dagg and company

Television (Excerpts) – 1973

His Name is Dagg

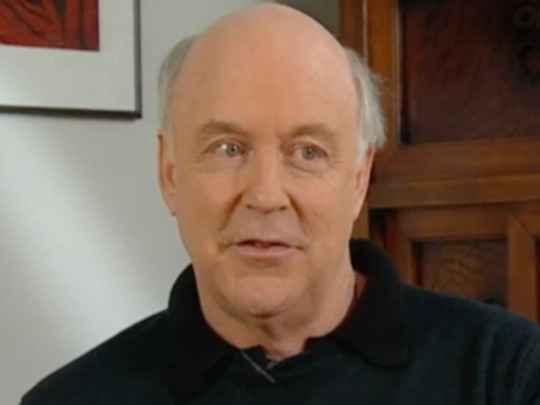

John Clarke was fascinated with the fine details of how people speak; how words can make a story more interesting in the retelling, how they can exaggerate and evade, and how words (including poetry) can make their own kind of music. Clarke's fascination with words and storytelling fed into his best comedy — like his character Fred Dagg, and his interviews with Bryan Dawe.

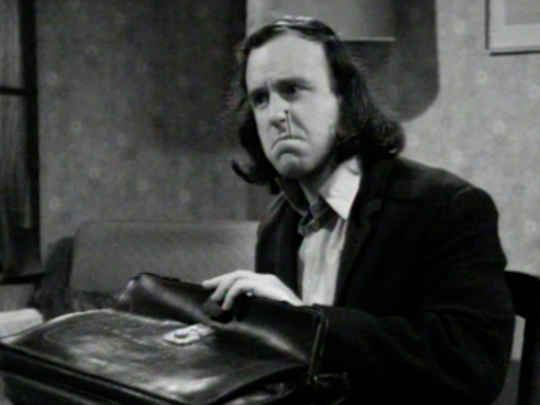

When Fred Dagg first appeared in 1973 — on a current affairs show — he was part of a Kiwi trend where television comedy was still relegated to the sidelines, and not permitted a slot of its own. Fred Dagg's comic power quickly won him fans, even though his appearances rarely went for more than three minutes at a time. The character spoke with enormous confidence in a New Zealand accent, at a time when local TV presenters tended to sound like they were from England. As comedy veteran Paul Horan has said, Dagg's comedy "slotted into who we were; it wasn't over the top, but it was eloquent ... he was clever, and didn't speak down to you."

It's not easy to trace exactly when Fred Dagg first emerged — and how he developed. Although there's good evidence to show that Fred Dagg debuted on TV's Gallery in late 1973, Clark performed similar characters back at university — and probably earlier still.

As a child, Clarke tried out "different accents and appearances". Dagg, he once said, "grew up alongside me". The character drew inspiration from many voices: "a couple of very amusing uncles"; the distinctive sound of racehorse commentator Peter Kelly, and others Clarke met, who were "obvious and surreal, saying nothing and talking interestingly".

Clarke later noted the following as key influences on his comedy: a love of language and how New Zealanders spoke, and the way that British comedian Peter Cook constructed "a seperate and completely plausible universe inside his own head".

As the 1970s began, there were early Dagg sightings. When Clarke began acting in university revues (which combine comedy and music) in Wellington, his comic chops were soon noted. Fellow Victoria University student Simon Morris recalls one show where Clarke was "riveting", amidst the chaos around him. "He was a great improv person, old John".

One in Five opened on 3 May 1971. The hit show was pulled together by Roger Hall after Victoria University's annual revue fell over. Clarke would trace a direct line from the show to Fred Dagg. In one sketch, Clarke's character Bruce spells out his name to a mate over the phone. In another, Clarke's Farmer Brown wore a singlet, shorts and gumboots (the sketches can be heard on album The Brian Edwards Show).

Clarke then lived in London, where he met comedy heroes like Peter Cook and Spike Milligan. But as Clarke explained (40 minutes into this interview) his real interests lay elsewhere. He was keen to do something with the place he knew. "I needed to find a way in which being me was a living".

In December 1973 Fred Dagg made his screen debut on Gallery. Clarke had been invited to add some light relief to the long-running current affairs show. "David Exel was the reporter and we had to give the character a name. He thought Fred. I thought Dagg. So it was." In another interview, he recalled his keenness "to do something on television that had some impact". What was needed was "a recognisable kind of iconography ... a hat, a black singlet.."

Dagg went on to become a regular fixture thanks to his short, often improvised items on Nationwide and Tonight at Nine. Sometimes Clarke became a one man band, operating the camera alone. But it was easier when he had someone to spark off; like when he was interviewed by one of the reporters.

Clarke shines in best of compilation The Dagg Sea Scrolls (2006). "Public response was immediate and very gratifying," says Clarke. "And a good thing too, because there were some jitters at what might be called the management level in New Zealand broadcasting at the time."

Dagg proved he could do more than monologues, with this beloved 1974 episode of Country Calendar. Dagg was becoming a major star: passers-by honked horns and asked for autographs. To ease his workload, Clarke asked his uni colleague John Barnett to become his manager.

Meanwhile Clarke was grappling with some in state television who seemed reluctant to let him off the leash, perhaps fearful of critiques of the status quo. Arrogance also had a part to play. This was an age where if a show ran too long, a director was liable to solve things by throwing away the final six pages of the script (as happened one time on Buck House). Facing challenges getting a longer TV show going, and earning little from his TV appearances, Clarke diversified. Fred Dagg featured on T-shirts, albums, and ads (one potential client ended up tripling their offer for Dagg to advertise their product; they got turned down). Dagg's first book Fred Dagg's Year (1975) won advance orders of 30,000. The following year Clarke did an extensive live tour.

Album Fred Dagg’s Greatest Hits proved a major hit. The beloved 'Gumboot Song' (aka 'Gumboots') was born after Dagg needed a big finish for a live show with female impersonator Marcus Craig. "It was hastily cobbled together", based on a Billy Connolly track (itself inspired by another song).

In 1977 Clarke moved to Melbourne. But Dagg brought him back. As a favour to director Geoff Murphy, he made half-hour romp Dagg Day Afternoon (1977). Costa Botes writes here that it was part of a double bill with Murphy's romp Wild Man. The following year, Clarke presented The Fred Dagg Lectures on Leisure. The now lost TV series covered everything from UFOs to saving whales.

Clarke stayed on in Australia until his death in 2017; his most Kiwi of creations lasted just a few more years. Alongside 1979 album The Fred Dagg Tapes, Dagg was syndicated across Aussie radio until around 1980. Many of Dagg's wise words ended up in anthology books like A Dagg at My Table.

At one point there were even plans for a full-length Fred Dagg movie. In 1979 Clarke described the script as his "magnum opus" — a "carefully constructed piece of satire with a carefully considered story". One draft, written with Roger Simpson, reached 160 pages. It would have been great to see.

- Ian Pryor is editor of NZ On Screen.