2000 Today - Millennium Concert with Kiri Te Kanawa

Television (Full Length) – 2000

Taking New Zealand to the World - New Zealand’s Television Coverage of the Dawn of the Year 2000

When I got the call to come and have a meeting about a millennium television special for TV3, it felt like a dream come true. I’d been involved in directing and producing live TV specials for a number of years, but this was next level: a 30-hour live-to-air event covering New Zealand and the world, as it transitioned from 1999 to the year 2000. Additionally we'd be contributing to a global television special, 2000 Today, created by the BBC and American television network WGBH.

As one of 80+ countries signed in to the project, we had an abundance of material to cherry-pick for our viewers — but also the responsibility to deliver some crucial content to the world. Being the first country to see the light of the year 2000 put us in an enviable position on the global TV schedule. The event had a huge emotional and spiritual connection which was too big to ignore, hence all the hype.

Producing and directing live TV specials is a lot of work, and comes with a high degree of risk. You have limited control over what's occurring in front of you, but you also need to find the best viewpoint for your audience, to help give them a sense of being there. As with live sport, you have very little influence on how things unfold, and can't ask for a second take if things don’t work out as expected. Plus in this case, we'd be transmitting live to the rest of the planet; the pressures of expectation were immense.

When normally I'd have my hands full with one event, this time I'd be managing eight live events at once, all of them outside and at the mercy of the weather (which ended up having a huge impact). So in the best traditions of broadcasting, we planned the production to the last detail, but left room to deviate from the plan if required.

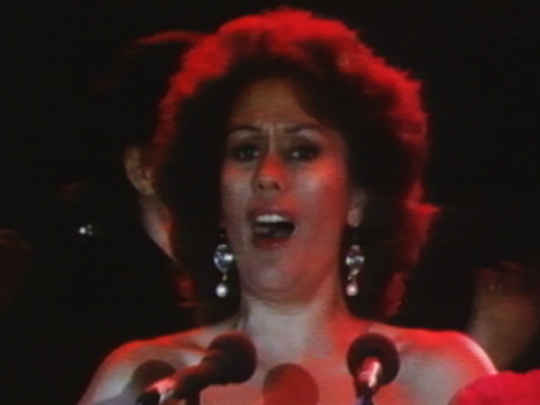

The production was financed by the government and TV3 won the bid to be the official broadcaster for New Zealand — a real coup since the state-owned TVNZ was arguably the obvious choice. We spent all of 1999 pulling together the logistics of covering all the events around the country, while also managing the associated politics and risks. Some of the events fell apart, months, even weeks, before the big day. Most significant for us was Odyssey's End, set for Gisborne. The mega-concert had big names attached, including David Bowie, Split Enz, and at dawn, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa with the NZ Symphony Orchestra. We were still in negotiations when word got out that things were looking shaky.

The reality was that the scale of the event was bigger than the Gisborne region could handle. In August we got word that it wasn’t going ahead. This was both devastating and fortuitous for us, as we hadn’t sealed the deal yet. It gave us an opportunity to offer alternatives to Dame Kiri and Split Enz, which meant TV3 could be more directly involved. So we became executive producers of the event, in addition to broadcasting them. Through the brilliance of our executive producer Logan Brewer, we were able to negotiate putting Split Enz on a floating stage at Auckland's Viaduct Basin, and Dame Kiri and the NZSO on Gisborne beach at the dawn of the year 2000.

The stage set up at Midway Beach in Gisborne, two mornings before lift off. Photo by Howard Anderson

The dawn concert. Photo by Howard Anderson

This was no small feat. Staging a concert of international quality for a worldwide audience of 800 million potential viewers, on a beach in a city with little local infrastructure for such a big concert, proved extremely challenging. The logistics were complex. Especially critical was positioning the stage so that the audience had a view of both the concert and the sunrise. We found a suitable spot, but it required temporarily relocating a number of 100-year-old trees into a nursery, and flattening a sand dune to build the stage. All of this had to be remediated back to how it was before the event (which it was). We also needed to get 100+ members of the NZSO plus instruments, and Dame Kiri’s entourage, in and out of Gisborne for the event, ready to perform on the morning of the concert at around 5:30 am.

I'd contracted Wayne Leonard to direct the event so I knew the pictures would look great. But I still had the audio to sort and that was a huge part of the package. The concert needed to have excellent audio quality. A 90 piece orchestra can sound incredible; and with the world's greatest soprano singing up front, this had the potential to be a historic piece of television. It also carried high risk factors, due to the innate technical complexity, seaside location, time of day, and going live to the world with no opportunity for an on-site rehearsal before the actual performance.

I wasn’t sure how to pull this off, before a stroke of luck: I learned that Dame Kiri was flying in from England just before Christmas to spend time with family, before heading to Wellington for three days rehearsal for Gisborne, with the NZSO, at the Michael Fowler Centre. Perfect. It was our opportunity to sound check the entire setup. With 120+ channels of audio — each with specific volume levels, equalisation, compression and position in the stereo mix — it would take three days to configure, clearly an impossible task on a crowded beach at midnight.

The lighting control desk. Photo by Howard Anderson

So I arranged for our sound team to travel to Wellington to set up the entire audio system in advance — both the live mix for those watching on the beach, and the broadcast mix. At the end of rehearsals, the mixing desks were simply powered off, with everything set and ready to go. The equipment and team were then shipped to Gisborne, where the gear was unpacked and set up exactly as it had been in rehearsal — every position onstage, every microphone on each instrument patched into exactly the same channels. It worked — perfectly.

The issue of how to move the NZSO from Wellington to Gisborne required more lateral thinking. With no options for accommodation, it became clear we'd need a fly in, fly out arrangement. Plans were made to fly the entire orchestra out of Wellington just after midnight, using an RNZAF Hercules. They took it all in their stride, arriving safe and sound at around 2am before heading to the beach.

The morning of 1 January in Gisborne was calm. The crowd gathered before dawn to be part of a historic event. In front of the stage, 15,000 sunflowers had been used to cover a mound of dirt. Dame Kiri appeared just as the BBC took the New Zealand feed to the world, for what was originally set to be three songs. At the end of the third song, a voice came down the comms line from BBC London. "We think we’ll just stay with you New Zealand…" Another song live to the world. At the end of that song came another call. "We’re going to stay with you for one more.." We ended up feeding more than 13 minutes live to 80+ countries, and around 800 million viewers. Over the 48 hours following Kiri's performance, she's said to have sold 14 million albums worldwide.

The Waihirere Māori Club in action.

Tall ships and waka: after the concert — Midway Beach, Gisborne, 1 January 2000. Photo by Howard Anderson

Another big millennium event was dawn on Mount Hikurangi, on the East Cape of the North Island. This is an area of national significance, as it's the first place on the New Zealand mainland to see the light of the new day. The maunga is a cultural taonga for Ngāti Porou. We were there as guests of the iwi and strategic partners in presenting the event to the world. In recognition of the occasion, a major artwork was commissioned, from celebrated Māori artist Sir Derek Lardelli: a series of large scale sculptures depicting the legend of Maui. The eight individual pieces were set in a circle, with Maui in the centre. It was truly a magnificent sight to behold.

But where to install it? With a radius of roughly 35 metres of perfectly flat land required on the side of a mountain, some significant earthmoving lay ahead. We made several trips up the maunga in four-wheel drive vehicles, followed by at least another hour on foot, looking for a suitable site. In cooperation with Ngāti Porou and Sir Derek, a location was settled on.

Then came the task of creating an access road and preparing the site. Ngāti Porou took responsibility for this task, and did a fantastic job in widening, extending and strengthening the road up to the site. One thing I was insistent on was having a helipad somewhere nearby: an important health and safety consideration, since around 100 people were expected on the maunga for the event, including a number of Ngāti Porou kaumatua and Prime Minister Helen Clark.

Soon everything was in place. About five days before the big day, a huge storm hit the East Cape. Torrential rain came down from the mountain ranges, washing out the only access bridge over the Tapuaeroa River, which we needed to get our equipment up to the site. Plus parts of the newly created road up the mountain had fallen victim to slips. We had a problem — a big one. Luckily, as part of our contract with the crown, we could call on the armed services once again. A quick call to the RNZAF rustled up some Iroquois Helicopters to ferry all our crew, equipment and portacabins up to the site. After that, the Iroquois became a de facto ferry service for the VIPs and kaumatua participating in the ceremony.

Everyone needed to be on-site before dusk on New Year's Eve, so it was a long night for the team on the mountain. Weather was marginal, with nasty rain squalls blowing through, but they toughed it out. The dawn promised a slightly more settled morning. The ceremony was as passionate and moving as anything I have seen. Ngāti Porou did themselves proud and were presented to the world, as the first light hit mainland New Zealand.

These were just a few of the highlights of New Zealand's millennium broadcast. It was an unforgettable time — and a piece of Kiwi broadcasting history I'm proud to have been a part of.

- Richard Hansen supervised New Zealand's many contributions to the international Today 2000 millennium broadcast. Read in this profile about his efforts to film a New Year's fireworks display after the helicopter was grounded.