Mauri

Film (Excerpts) – 1988

There's a raw, edgy power at work in Mauri which overrides its technical deficiencies . . . Mauri is an emotionally charged piece of cinema. Mita successfully infuses the notion of spirituality that comes from both the people of the land and the land itself, without slipping into vague mumbo- jumbo. The term Mauri translates roughly to 'life force'. Mauri has a mauri of its own.

– The Auckland Star, 28 September 1989

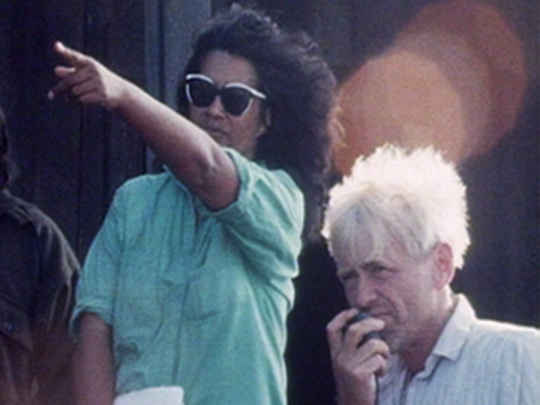

She says Pākehā technicians were brought in to satisfy the demands of the Film Commission and investors who wanted assurance the film's technical quality would be up to scratch. She adds with satisfaction a full 33 of the 53 strong crew were Māori in spite of the demands of the film's backers.

– Writer Phil Twyford in an Auckland Star interview with Merata Mita, 23 June 1987, page B1

[Filming was] littered with people who were obstructive, racist, arrogant and of little or no use to the production. In fact, when we booted the whole lot out things went a lot better. We saved so much money.

– Merata Mita describes the making of Mauri in The Auckland Star, 23 June 1987, page B1

We had people working on the film who objected to the locations I had chosen, who tried to shorten the script and cut out all the marae scenes because they didn't understand them.

– Writer/director Merata Mita on the challenges of making the film she wanted, in The Auckland Star, 23 June 1987, page B1

This film Mauri is about birth and death, and all that takes place between. It deals with the essence of life, the essence of attraction, joy, sorrow, grief. It goes through a whole spectrum of life that Māori live...

– Writer/director Merata Mita describes the film, in 1987 documentary Koha - Mauri

The difficulties and conflict during the shooting of Merata Mita's film, Mauri, arose more from pervasive inexperience on and off the set than from the prejudice and racism Miss Mita would have us believe.

– Camera crew Graeme Cowley and Paul Leach respond to Merata Mita's comments on racist (unnamed) crew working on the film, The Auckland Star, 30 June 1987

The Māori reponse to the film was more positive than the Pākehā one, but that was the way it was from the beginning; from the scripting to the final cut. It was a quietly satisfying moment to enter the theatre on the opening night of Mauri and feel the pride of so many brown faces. I am very proud to have made something for us, so relentless and uncompromising, for me it was another brief fulfilled.

– Writer/director Merata Mita, in 1992 book Film in Aotearoa New Zealand, page 49

It was a collection of experiences over about 40 years in which there seemed to be this conflict situation in Māori society which was increasing rather than diminishing. And that there seems to be no resolution to it within the confines of society as it is today. And that given that set of circumstances there had to be some kind of opening there, some kind of resolution so that the conflict situation could be resolved without violence and that's what I was looking at in the film, trying to find that pathway that would lead to resolution without violence.

– Writer/director Merata Mita on the inspiration behind the film, Monitor, October 1989

...the Fourth Cinema movement spearheaded by Māori filmmaker Barry Barclay can legitimately be claimed by NZ, and there are few better examples of Fourth Cinema than Merata Mita’s Mauri. Mauri, the first feature written, produced and directed by a Māori woman, is a sinuous tale of guilt, tradition and family, threaded with an examination of Māori/Pākehā societal politics and more than a dash of the supernatural.

– Website Cinema Aotearoa

You stay away from here . . . you might own everything else around here, but not this place.

– Rewi (Anzac Wallace) to Steve (James Heyward)

It's you she's got the hots for.

– Kara (Eva Rickard) to Rewi (Anzac Wallace)

...a woman like her in real life was the woman that the character was meant to represent.

– Writer/director Merata Mita on getting land rights activist Eva Rickard to act in the film, in 1992 book Film in Aotearoa New Zealand, page 49

...the story is really a parable about the schizophrenic existence of so many Māori in Pākehā society. Our psychological prisons are sometimes worse than jail, and only by breaking free of colonial repression and asserting our true Māori identity can we ever gain real freedom.

– Writer/director Merata Mita on Mauri, in 1992 book Film in Aotearoa New Zealand, page 49

Māori filmmakers have to address several issues not of their choosing when they decide on a project of fiction. They have to satisfy the demands of the cinema, the demands of their own people, the criteria of a white male-dominated value and funding structure, and somehow be accountable to all. . . . the Māori filmmaker carries the burden of having to correct the past and will therefore be concerned with demystifying and decolonising the screen. The expectation of positive imagining means destroying the stereotypes that come from cultural appropriation, and clearing the colonial refuse out of oneself in order to make a fresh new start.

– Writer/director Merata Mita, in 1992 book Film in Aotearoa New Zealand, page 49

[The film is] a fluid and organic exploration, from a Māori perspective, of what it means to be Māori in a twentieth-century Aotearoa New Zealand. Here, as in Ngāti, Pākehā are the outsiders, the foils in a Māori-centred story: they are the spectators and transgressors.

– Writers Jocelyn Robson and Beverley Zalcock, in their 1997 book Girls’ Own Stories - Australian and New Zealand Women's Films, page 55

In this brief footage, lasting little more than two minutes, the film's key concerns have been mapped out: the rhythm of the life cycle, the inextricable bond between the people and the land, the significance of community, the value of acquired wisdom and the importance of all things of a cultural perspective.

– Writers Jocelyn Robson and Beverley Zalcock on the opening sequences of Mauri, in their 1997 book Girls’ Own Stories - Australian and New Zealand Women's Films, page 56

Death has a way of calling out the truth in all of us.

– Kara (Eva Rickard)

There are stunning images of the landscape throughout but perhaps most memorably in the final sequence . . . A heron flies and the camera circles high, tracing the contours of the land above the tiny community; a low sound like wind gradually gives way to women's voices singing in Māori and a small girl, who has watched and waited and learned throughout, runs to the hilltop to wave farewell to Kara's departing soul. The camera circles and finally draws away, as if it is itself Kara's spirit in flight.

– Writers Jocelyn Robson and Beverley Zalcock, in their 1997 book Girls’ Own Stories - Australian and New Zealand Women's Films, page 58

[The film is] an attempt to find an appropriate form in which to tell the stories of a community. These are stories in which the community itself has centrality, rather than any individual character, and the film's narrative structure is correspondingly more diffuse, containing as it does a number of narrative resolutions within it . . . here the process of telling may be more important than any one story itself.

– Writers Jocelyn Robson and Beverley Zalcock, in their 1997 book Girls’ Own Stories - Australian and New Zealand Women's Films, page 58

At times, the film looks a bit like a western (there are campfires, a shoot-out, gangs, and episodes of honour and betrayal) but there are no stars and women are central. In many ways, this is a film about relationships, rather like a melodrama, but the nuclear family is replaced here by a more inclusive form of kinship, a network and a community.

– Writers Jocelyn Robson and Beverley Zalcock, in their 1997 book Girls’ Own Stories - Australian and New Zealand Women's Films, page 58

[The film is] quite distinctive and easily one of the most powerful and important yet to come out of new Zealand.

– Writers Jocelyn Robson and Beverley Zalcock, in their 1997 book Girls’ Own Stories - Australian and New Zealand Women's Films, page 59

...I really wanted to destroy the massive sentimental view of Māori people, like we're the sort of people who have this lovely mystical thing called Māori and we go on maraes and do lovely things . . . I wanted to destroy all this, because Māori eat, drink, live f**k, fight, do everything that normal people do

– Merata Mita on Mauri, in an interview with Cushla Parekowhai, Illusions 9, December 1988, page 24

...they're so used to that other sort of hero like the ones in the ads, they're all white and they're the only ones that use Lux . . . you're always creating a lot of interest or disturbance as well among Māori people, particularly the ones who are just as colonised as Pākehā people are. I think the whole process of decolonisation had better take place soon and it had better take place fast so that we can accept the authentic image of ourselves as we see ourselves as being the correct one, and not the one that the Pākehā has always presented to us.

– Merata Mita on reactions to Mauri having Māori lead characters, in Illusions 9, December 1988, page 24

We had a number of young Māori people working on the film crew. . . . what you gain from Māori people is an incredible intensity and passion about the work being done. From a professional crew you get professionalism. From a Māori crew you get passion. . . . The success of our trainees of Mauri has made it worthwhile.

– Merata Mita, in an interview with Cushla Parekowhai, Illusions 9, December 1988, page 22